Understand Your Rights. Solve Your Legal Problems

EIP partner Gareth Probert examines the data and what it indicates for global IP in this special feature.

Each year, the European Patent Office (EPO) releases its Patent Index report outlining patenting activity on the continent. While this is always of interest to professionals in the intellectual property (IP) space, this year’s report bears reading across sectors for what it says about the state of innovation not only in Europe but globally.

In short, it is positive reading; after a couple of years of disruption, patenting activity is continuing to grow as companies find new ways of tackling the problems we are facing in Europe and beyond. While the growing number of patents filed by non-European tech giants is significant for certain industries, it is largely counterbalanced by the strong performance of Europe’s own start-up scene.

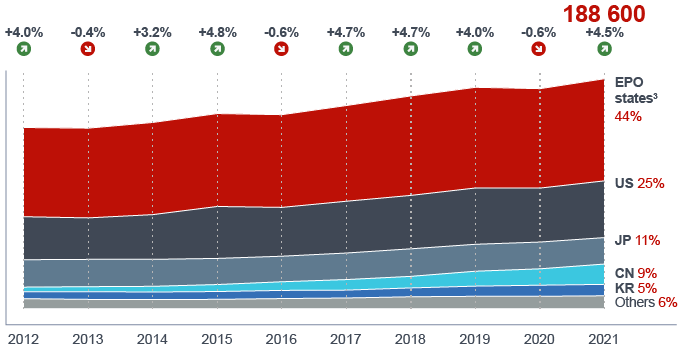

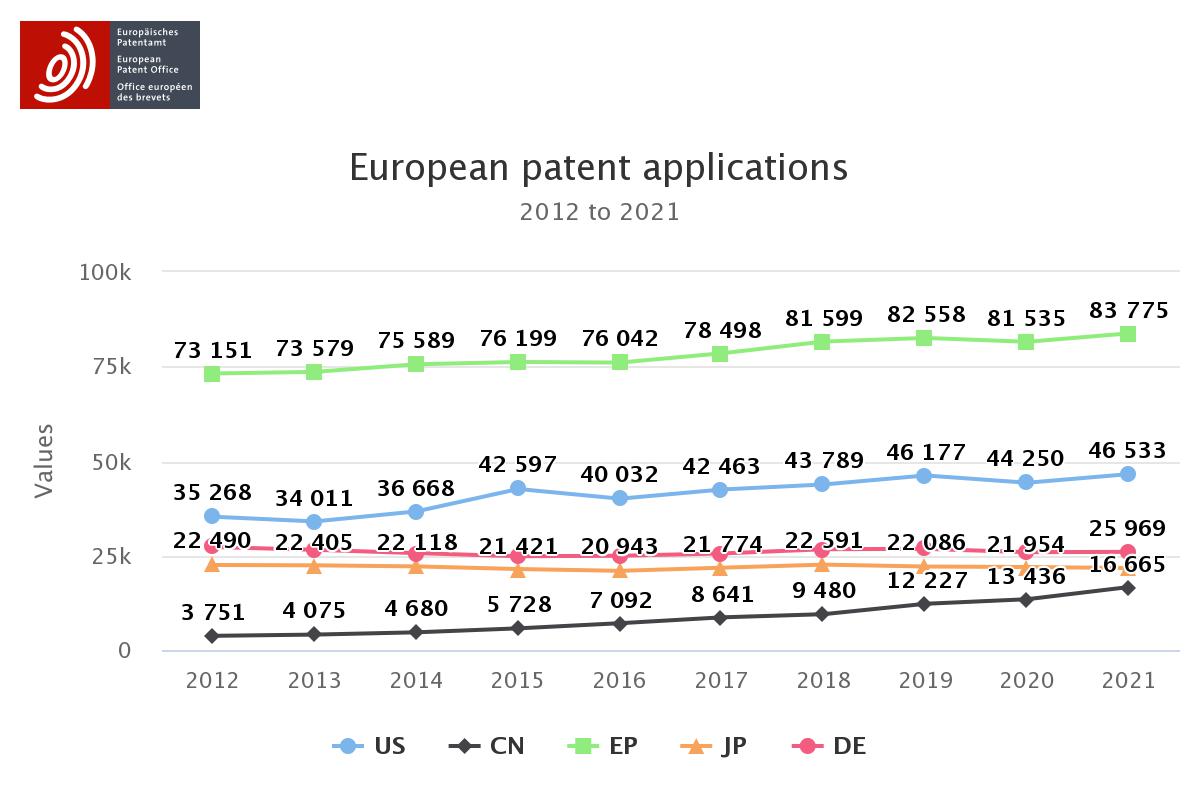

With over 4,200 patent examiners, the EPO handles a huge number of applications each year from individuals, universities, and companies from all around the world. In 2021, a total of 188,600 applications were filed at the EPO, which includes new applications filed directly at the EPO, applications derived from International (PCT) patent applications and divisional applications derived from existing European applications. Amazingly, this means that roughly 700 applications are received by the EPO every working day!

After a slight drop in numbers in 2020, filings have rebounded with a more typical increase of 4.5% in 2021, partly driven by the unique conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic.

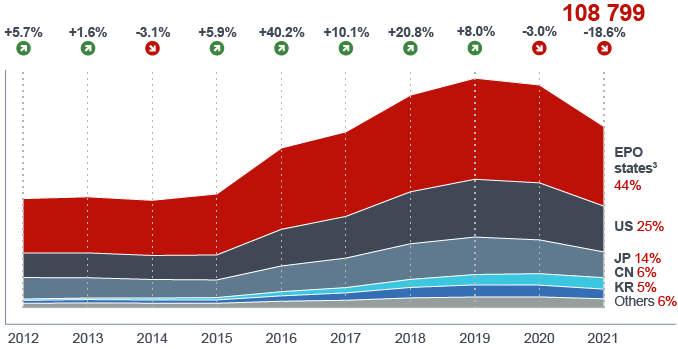

Looking at these numbers alone can be misleading, as applications can be filed for many reasons and with varying chances of being successfully granted. So, to gain some perspective it is important to also have a look at the number of patents being granted by the EPO. There is of course a delay of a few years from filing to grant, but there are clear trends visible in the new statistics regardless.

Users of the EPO are familiar with the management’s drive to increase perceived efficiency and timeliness, and the aim to reduce the backlog of cases (euphemistically called “stock” by the EPO). It seems that this ambition has led to a dramatic increase in the number of cases being granted from 2015 onwards, with examiners being encouraged to dispose of older applications more quickly. However, this activity peaked in 2019 with 137,784 European patents being granted and has dropped since then to a total of 108,799 patents being filed in 2021. Much of this could be the result of COVID-related disruptions to normal working patterns, meaning next year’s granting figures will tell us much more about how the EPO has adapted to home working for examiners.

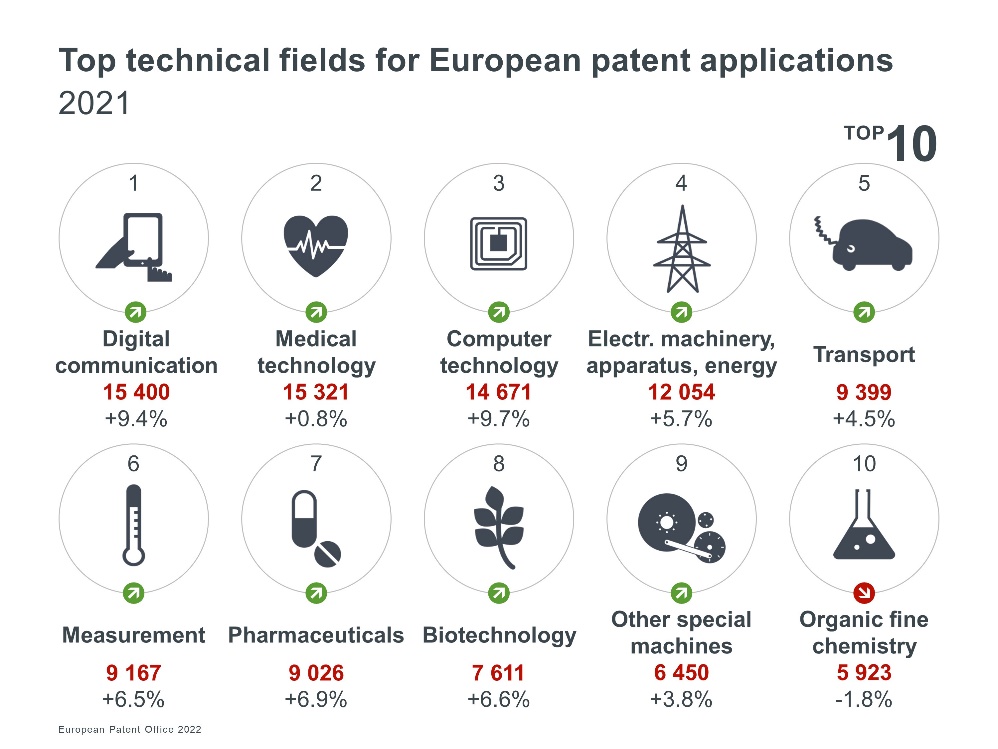

Medical technology has been the sector with the most applications for most of the last decade according to the EPO, with digital communications running a close second. In 2021, digital communications finally claimed the spot as the most popular technology with 15,400 applications, just 79 more than medical technology. Applications involving computer technology are not far behind, showing continued growth over recent years.

These statistics must be seen as a rough indication, however, as innovations are becoming more interdisciplinary over time. Many applications are based on combinations of traditionally separate technologies. For example, 5G technology allows medical devices to connect to each other and networks to enable the Medical Internet of Things (MIoT). The EPO statistics would perhaps classify such a medical device as either “digital communication” or “medical technology” depending on the examiner’s view of the most relevant technology claimed in that specific patent application. It may be difficult to achieve, but a more nuanced analysis of the technologies of new innovations would be extremely valuable to all parties. More detailed data could highlight what combinations of technology are giving rise to modern inventions.

Pharmaceutical and biotech applications saw some growth in 2021, but perhaps not as much as expected given the need to tackle the global pandemic. However, many of the mRNA platform technologies underpinning the COVID-19 vaccines had been developed and protected in previous years. There were huge efforts to develop effective vaccine platforms to tackle the SARS, MERS, Ebola and Zika outbreaks in recent years, and many of the COVID-19 vaccines were able to build on this existing knowledge base.

After a couple of years of disruption, patenting activity is continuing to grow as companies find new ways of tackling the problems we are facing in Europe and beyond.

Another way of slicing the data is by the originating country of the applicant. This is useful, but again blurs some details, especially where there is more than one applicant or if a company’s headquarters is in a different country from where the research is carried out. Applicants in the EPO member states are the biggest filers yet again, with 44% of all applications filed. Although the official statistics place the US in second place with 25% of cases, it is in fact the single country with the largest number of applications, ahead of EPO-member Germany with 14%.

Japan continues to be represented with a steady 11% of cases, but China is closing fast. Over the past decade, economic and technological growth in China coupled with government incentives has resulted in increasing number of applications at the EPO. The 24% increase going from 2020 to 2021 is remarkable and may lead to China surpassing Japan and perhaps Germany in the next couple of years.

The last way to view the data is by the applicants themselves. Again, there is uncertainty resulting from cases with multiple applicants, different companies within a group and from how the names of companies are entered onto the EPO register. For several years the same three companies have jostled for position of the most prolific filer at the EPO, namely Huawei, Samsung, and LG. After Samsung took first place last year, Huawei have returned to the top spot with an astounding 3,544 application filed in 2021, with LG keeping their third place. Notaby, Huawei is responsible for about a fifth of all applications originating from China.

Whilst the performance of Huawei, Samsung and LG is impressive (not least in terms of the hours spent in writing all those specifications), there are differences in filing strategies in different sectors and companies. The value of a single application to a global telecommunications giant may be very different compared to a start-up based on a new technology.

It may be more interesting to look at the tail of smaller portfolios for SMEs rather than the top ten applicants. While 75% of all European applications come from large enterprises, an impressive 20% originate from SMEs and individuals (with 5% coming from universities).

It is my experience that many of these SMEs are developing interdisciplinary products and processes that have the potential to be disruptive to existing companies. Also, these smaller companies can be dependent on government grants and investor funding, especially if they are tackling environmental or climate-related problems.

[ymal]

In amongst these cases are technologies underpinning vaccines, diagnostic tests, videoconferencing, collaborative working, automated vehicles and batteries, all of which have become increasingly present in our lives. At my own firm, we see these fascinating new technologies as we help companies to identify, protect and enforce their IP in Europe.

All in all, things are looking good for the wider European patenting landscape. After a slight pause, more applications than ever are being filed across the continent. The encouraging patent data also shows that the EPO has adapted well to the new normal of remote working and videoconference hearings. Innovative companies around the world are keen to protect their IP in Europe, and the EPO continues to meet that challenge.

Gareth Probert, Partner

EIP, Fairfax House, 15 Fulwood Place, London WC1V 6HU

Tel: +44 020 7440 9510

Fax: +44 020 7117 5111

Gareth Probert is a partner at EIP and an IP lawyer with over 20 years of experience, having represented clients in many opposition and appeal hearings at all levels of the European Patent Office. Over the past 10 years, he has held senior positions at two leading IP firms and is now head of the EIP HealthTech practice group. Protecting innovations in the medtech and healthcare sectors.

EIP is a leading intellectual property firm comprising patent attorneys, litigators and commercial IP lawyers based in Germany, the UK and the USA. The EIP team advises on high-value and complex patent matters and is highly ranked across all six technology sectors in Europe's Leading Patent Law Firms 2022.

Unravelling these issues typically requires the knowledge of a family law attorney with experience in handling cases pursuant Hague Abduction Convention. Richard Min, a leading authority on such abduction cases, delves further into this subject below.

Child abduction and kidnapping are often used interchangeably, though the term “child abduction” is usually associated with the 1980 Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction (“Hague Abduction Convention”), which is a civil treaty between approximately 100 countries, including the United States. The term “kidnapping,” on the other hand, usually references criminal behaviour, such as defined by the International Parental Kidnapping Crime Act of 1993 (“IPKCA”), which makes it a federal crime to take or a keep a child outside of the United States in violation of another person’s parental rights.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children estimates that approximately 200,000 children are abducted each year by a parent of other family member, though that includes both domestic and international child abductions, which are governed by different sets of laws. The United States Department of State – tasked with overseeing international child abduction cases – stated that during 2021, they handled 679 active abduction cases involving 904 children. Of course, not all cases of abduction, be they international or domestic, are reported to the authorities.

Oftentimes, parents may be unaware that they have engaged in child abduction for a variety of reasons. They may believe they had the right to relocate to another state or country without the other parent’s permission. They may be victims of domestic violence simply fleeing a dangerous situation. Or they may be living in a foreign country simply desiring to return to their own country to be closer to their own families.

As is often said, ignorance of the law is not a defence, but there are valid reasons or defences that can be raised when confronted with allegations of child abduction. As mentioned previously, escaping domestic violence can sometimes legally justify a child abduction, as can a consideration of the interests of the child, including how long they may have resided in the other country and whether the child has a strong objection to returning to the original country.

Oftentimes, parents may be unaware that they have engaged in child abduction for a variety of reasons.

There are several risk factors, many of which have been codified under the Uniform Child Abduction Prevention Act, a law existing in approximately 15 states. The risk factors include whether a parent has previously abducted or threatened to abduct a child or has a history of noncompliance with court orders or co-parenting or has stronger ties to a foreign country than the current one, including financial, familial, and/or legal (immigration).

First, litigating child abduction cases will vary heavily depending on whether the abduction is domestic versus international. If the abduction is domestic, the laws will be usually similar between different states because the Uniform Child Custody Jurisdiction and Enforcement (“UCCJEA”), which would normally be applied in domestic child abduction cases, has been passed in 49 of 50 states. The UCCJEA prevents courts in differing states from issuing competing custody orders and mandates that only one state be permitted to issue orders related to the custody of a child. Therefore, if a child is abducted from one state to another, the state where the child is taken to will typically have to enforce and comply with the directives of the home state.

In international child abduction cases, litigating these cases can vary much more greatly between different jurisdictions. I have litigated child abduction cases in approximately 15 different states and the process can look quite different depending on where the case takes place.

First of all, the application of the law (case law) depends in which of the 12 regional circuits the case takes place. Though the US Supreme Court has decided five very important Hague cases (the most recent being my case) in the past dozen years, thereby resulting in greater uniform application of the law, it is still the case that different circuits have a different interpretation of the Hague Abduction Treaty. In addition, courts move at different speeds in different jurisdictions, so you may be able to get resolution of a Hague case within one month in one court where it may take six months in another. Hague cases are supposed to be acted upon expeditiously, but depending on the issues being raised and the workload of the particular court or judge, cases may take longer to resolve.

Litigating child abduction cases will vary heavily depending on whether the abduction is domestic versus international.

The US Department of State issues a yearly report on international child abduction cases, including those in which an American child was abducted abroad. Included in that report is an analysis of other countries’ compliance record to see how well the treaty is working between different countries. That being said, the process can look very different depending on where a child is taken to. Some countries have civil legal systems while other have common law systems like ours. Some countries have public prosecutors that can bring these cases on behalf of parents while in others you have to find and pay for your own attorney, again as would typically be the case here in the United States.

A major difference, of course, is whether the child is taken to a “Hague” country or a “non-Hague” country, meaning whether or not said country adheres to the treaty. If they are a “Hague” country, then the process – albeit perhaps a bit different from other treaty member countries – will generally be the same in that you will have the same law to rely upon. If the child is taken to a “non-Hague” country, the process will vary greatly depending on the country and their own domestic laws and the particular facts of the family. Some countries may simply enforce any US custody orders, while others may not be so willing. It is always wise to immediately seek the advice of local counsel in those situations, which your US attorney or the State Department might be able to help with. You can always visit the International Academy of Family Lawyers website, which is a great resource for lawyers across the world.

Cases can be challenging for many reasons. There are procedurally challenging cases, such as cases with multiple actions going on simultaneously in federal court, state courts and even foreign courts. The case of Golan v. Saada, which I just argued in the US Supreme Court, was very challenging because it has been ongoing for almost four years, including a nine-day trial and numerous appeals.

[ymal]

The most challenging cases are those that involve horrific acts of child abuse. A recent case of mine involved two girls who had been terribly abused by their father and were terrified of being returned home. I felt tremendous pressure to make sure that they could be protected and, luckily, we were successful in keeping them here in the US. I also had a case where the child had been secretly abducted and withheld from the mother for two years without any contact. Usually, even in abduction cases, the parent has some idea of where the child has been taken, but in this case, it took two years to locate the whereabouts of this particular child. We were able to have the US Marshal service pick up the child from school without the father’s knowledge and brought to the judge’s chambers for a tearful reunion with her mother. We also were successful in then having the child returned home. Sometimes the most challenging cases can also be the most rewarding and that is certainly one example of that.

Richard Min, Partner

Green Kaminer Min & Rockmore LLP

420 Lexington Ave. Ste. 2821, New York, NY 10170

Tel: +1 212-681-6400 | +1 212.257.1944

Fax: +1 212-681-6999

Richard Min is a partner at Green Kaminer Min & Rockmore LLP in New York City whose practice focuses exclusively on family law, with a particular emphasis on international family law, child abduction and cross-border custody issues pursuant to the 1980 Hague Abduction Convention and the Uniform Child Custody Jurisdiction and Enforcement Act. He has extensive trial experience in Hague Abduction cases having been involved in approximately 100 cross border child abduction or custody cases in more than a dozen states and having acted as lead trial counsel in over 35 Hague abduction cases.

Green Kaminer Min & Rockmore LLP is a Manhattan-based family law firm that serves clients throughout New York and internationally. Their team assists in a wide range of family law matters including international child custody and child abduction disputes, as well as disputes concerning the division of foreign assets in international divorces.

In this article, experienced criminal lawyer Edward Rocha de Carvalho provides a more in-depth look at these aspects of the Brazilian system and how they affect the practice of law in his jurisdiction.

These are crimes described in specific laws against the financial system, such as tax evasion, money laundering and corruption. These offences constitute our central core of practice, especially when multinational elements are involved, and we have a team whose members each possess at least a Master’s degree in these relevant areas.

A central financial activity control organ (COAF) detects and reports suspicious financial activities to the police and the prosecution, and they can also conduct their own investigations. We also have different institutions that supervise the use of public money, and they can also report suspicious activities to the authorities (i.e. the CGU – Union´s General Control). Depending on the offence, the investigation should be handled by state or federal authorities, and federal judges are usually more technically prepared to deal with cases.

Money laundering: 3-10 years. Tax evasion: 2-5 years. Corruption: 2-16 years. Transnational corruption: 1-10 years. An attorney can detect and act to correct abuses by the prosecution and lower courts, asking for the dismissal of the charges, for them to be classified as administrative offenses, or even negotiate plea deals for individuals and leniency agreements for companies.

Besides that, of course, we have to learn the client´s business to understand better how to help them and conduct a thorough investigation of the case and its specifics if we have to go to the courts to discuss its merits. That has considerable importance on relevant decisions, such as trying the case or pursuing agreements to end it swiftly. Recently, leniency agreements and plea deals have been legalised in Brazil, so that is an option as well, and can be a perfect one depending on the case.

The Brazilian legal frame is substantial, and sometimes an action taken by the client can be seen as illegal by prosecutors when it is in fact perfectly legal. It is usual for a prosecutor to say that there has been tax evasion when a client just used permissions granted by law to pay fewer taxes, for example. That often happens due to entirely different interpretations of tax provisions, depending on whether the person is from the revenue service or a lawyer who guides the client.

The Brazilian legal frame is substantial, and sometimes an action taken by the client can be seen as illegal by prosecutors when it is in fact perfectly legal.

Money laundering laws are also very non-specific, allowing the prosecutors to try cases when there is not enough ground to support charges on related crimes, mainly due to the impact of the FATF recommendations. Brazilian authorities accepted the latter without considering the legal and constitutional framework, which causes everyday issues before the courts since there is not a complete match between the law and the constitution, so to speak.

Year after year, maximum penalties are increased in Brazil, and procedures are hardened, with no corresponding effects on the ability to control crime. For what it is worth, the old saying is still valid: the most effective way to prevent crime is to know that (due and correct) punishment is inevitable.

The problem is that recent criminal reforms allegedly tried to tackle relevant issues, such as corruption and money laundering. However, at the same time, they fragilised the need for sound evidence to convict someone and also broadened and facilitated the freezing of assets, making cases harder to try before courts.

The hardest part is working in a non-adversarial system. Brazilian prosecutors are strongly favored by the courts, with a few honorable exceptions, making the selection of one´s lawyer an essential part of criminal defence. Our entire legal system is based on Mussolini´s Codice di Procedura Penale (criminal procedure code), so one can only imagine what kind of provisions we have here. Of course, there have been legal reforms trying to correct that over the years, but the system – and the people who work on it – keep their old habits, making it harder to create a constitutional mindset. Legal doctrine always says that changing the law from a non-adversarial system to an adversarial one is not enough because we have to change the mindset too, and that is very hard for people who were taught how to think in a system that favours the prosecution.

However, foreign lawyers are always astonished to learn the vast importance of the judge's role during the investigation and even during the case before courts, i.e. that a judge can produce evidence if they find it insufficient. In adversarial systems, it is needless to say that their impartiality is compromised when they produce evidence. During hearings, prosecutors sit at the judge’s side, whereas the defence sits in front of them.

[ymal]

The most satisfying part of working as an attorney is helping the client and achieving a good outcome. Besides that, what makes me most happy is that by the end of the day, we have an opportunity to work with excellent lawyers worldwide, learning their legal systems and culture and building friendships. You realise that you always have something to learn, especially working with great minds abroad. There have been times where an answer to a question was opaque to me but obvious to a fellow lawyer, which is impressive. Different systems, completely different mindsets.

Edwardd Rocha de Carvalho, Partner

Miranda Coutinho, Carvalho & Advogados

Rua Alberto Folloni, 1400 - Ahú, Curitiba - PR, 80540-000, Brazil

Tel: +55 (41) 3072-2243 | +55 (41) 98876-4941

E: edward@mirandacoutinho.adv.br

Edward Rocha de Carvalho is a partner at Miranda Coutinho, Carvalho & Advogados and a certified Master in State Law by the Graduate Program of the Federal University of Paraná, with a specialisation in criminal law. He is currently a member of the OAB/PR Sectional Council and was ranked 4th place among the most admired specialised lawyers in Brazil for the field of criminal law and 3rd place among the most admired lawyers in Paraná by Análise Advocacia 500 in 2020.

Miranda Coutinho, Carvalho & Advogados is a boutique Brazilian criminal law firm incorporated in 1986. Its team of multilingual legal experts handle cases ranging from public law to economic criminal law, with experience in fields including administrative procurement and contracts, anti-corruption law, business law, civil liability and many others.

Nuno Cardoso-Ribeiro, a highly experienced Portuguese lawyer and a major voice in the legal representation of families and children, outlines some of the unique facets of the law in this feature, drawing upon 20 years of experience in family law. What are the unique aspects of divorce and family law in Portugal, and how is legislation in the sector continuing to develop today?

Most divorce cases in Portugal are by mutual agreement, and the same applies to parental responsibilities regulations. Both processes may be done outside the courts, in the Civil Registry Offices, which allows them to be swifter and cheaper. The role of the lawyer, in such cases, is to act as a mediator, alone or in collaboration with a colleague, to ensure an agreement that answers both parties demands and needs.

Unfortunately, such an agreement is not always possible due to disputes regarding property or parental conflict. In those instances, there is a need to resort to a court of law – but even then, we remain alert to the possibility of promoting a fair transaction, thus bringing the judicial process to an end, especially in disputes which involve children. The promotion and diffusion of practical alternatives for out-of-court settlement of disputes involving children is, in fact, one of the statutory objectives of the Association of Family Lawyers I co-founded in 2020 and that I currently preside.

As it is often said, “time of the children is not the time of the court”; they do not conform to one another. Parents risk losing the best of their children’s childhood to fruitless disputes, to the detriment of all concerned parties, especially the children. Our job is also to prevent this sad reality.

As a rule, joint finances and property are divided 50/50, according to the so called “rule of the half”. The biggest challenge is to ensure the correct identification and qualification of all the joint assets, according with the applicable property regime.

In Portugal – with a few exceptions (in which the law imperatively establishes the separation regime) – the future couple may choose, before marriage, which property regime they want. They can even set their own rules, different from the ones established in the model property regimes set in the Civil Code, within the limits of the law. In practice, this means that the parties may choose which assets will be shared or which are excluded from the communion, regardless of whether they were acquired before or during the marriage. So, of course, this makes the matter of asset qualification a challenge.

As it is often said, “time of the children is not the time of the court”; they do not conform to one another.

It is also important to verify which debts were paid, which estate was responsible for their payment (one of the spouses’ own estate or the joint estate) and which estate effectively ensured the payment, since this may originate an entitlement to compensations between estates or between spouses. The same applies to other compensation cases between spouses.

A particularly important example of theses compensations is the one recognised to the spouse who, for the sake of the couple’s common life, has excessively renounced to the satisfaction of their own interests, particularly those of a professional nature, with important patrimonial losses. This allows a fairer asset distribution between the couple, recognising the effort of the spouse who gave up work in order to secure the care of the children or the domestic chores.

Even so, the Portuguese legal regime leads to outcomes less advantageous to the non-working spouse (or to the spouse with a lower income) than other countries, since the state pensions received after divorce cannot be shared, regardless of the property regime. Similarly, the conditions to recognise spousal maintenance rights to the ex-spouse are quite strict.

In Portugal, like in the vast majority of western states, parental international child abduction is defined mainly by the Hague Convention of 1980, on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction – in short, there is an international child abduction when a child is taken or retained across an international boarder, away from their habitual residence, without the consent of the parent(s) with the right of custody. The Brussels ii Regulation also refers to this definition, adding important rules regarding the international competence of the Member-States Courts.

However, there is also space for national differences – with the biggest specialty, in Portugal, residing in the interpretation of the concept of “parental responsibility” and “right of custody”, since the latter is not used by our national law. Instead, as a legal rule, both parents will have the power to decide the big questions concerning the child’s life (the so called “exercise of parental responsibilities regarding matters of particular importance”), regardless of the residency model established in the parental responsibilities regulation.

In other words, despite the fact that the child habitually lives with one of the parents, both must decide together in which country their child will live. To put it simply, if we were to translate the Portuguese solution to the legal language used abroad, both parents would have a shared right of custody as a rule. Of course, this solution has a big impact on parental international child abduction cases, as it deems illegal almost any unilateral relocation or retention of the child outside their country of residence, enabling the activation of the Hague remedies.

The Portuguese legal regime leads to outcomes less advantageous to the non-working spouse (or to the spouse with a lower income) than other countries, since the state pensions received after divorce cannot be shared, regardless of the property regime.

Personally, I find that the Portuguese legal solution has many virtues. The decision regarding a child’s country of residence should not be taken lightly. After all, the change of country will have a significant impact on the child, determining changes in their upbringing and development. It should never, in any circumstance, be used as a means to keep one of the parents away from the child.

The attribution of the decision-making power to both parents allows for greater control over the decision – and in the end, if the parents cannot reach an agreement on the intended change of residence, the decision will be made by a judge, thus better guaranteeing its adequacy to the best interests of the child.

In our office, over half our clients are foreign or are involved in an international affair. Our team is composed by colleagues proficient in English, Spanish and French, and/or with a good written and oral comprehension of German. This is fairly important, since we deal with foreign clients, state entities, colleagues and documents on a daily basis, with which we must be able to communicate flawlessly for obvious reasons.

Different jurisdictions always pose an additional challenge, first and foremost because it requires specific knowledge and understanding, however minimal, of the functioning of foreign legal solutions and law systems. Many cases also demand international cooperation between colleagues in different jurisdictions, to ensure the best possible outcome to the client. For both of these purposes, we at Divórcio & Familia ensure an active participation in international lawyers’ organisations, such as the International Academy of Family Lawyers (IAFL) and the Union Internationale des Avocats (UIA), that I just recently joined, which gives us an excellent basis both for experience sharing and network building.

It may also be a challenge to effectively manage expectations. Sometimes clients want results based on their previous experiences in other jurisdictions that quite simply are impossible to replicate under the Portuguese jurisdiction. In fact, many Portuguese legal solutions are strikingly different from those prescribed by other European Union member states, let alone the US or UK – the different approach to the definition of parental responsibilities and spousal maintenance, as we have seen above, are but a few examples.

In our office, over half our clients are foreign or are involved in an international affair.

Therefore, it is very important to thoroughly inform the clients of their rights under the Portuguese law in order to offer them a sense of security regarding the possible outcomes of their legal proceedings. It is also important to give them the space to seek counselling abroad and acquire a broad picture of their rights under different jurisdictions, so they may take action wherever they find the most convenient solution to their personal interests. In Portugal and all other EU member states, the Regulation (CE) no. 593/2008, also known as Rome I, recognises the parties’ freedom to choose the applicable law, even if it is not the law of a member state – a very important faculty to consider, for example, in marriage and divorce by mutual agreement cases. Parallel solutions may also apply in foreign countries, with different international private law systems.

Being a relatively small country, the Portuguese Central Authorities register about 80 cases of international child abduction cases per year (divided into 40 children illegally retained in Portugal, and 40 children illegally taken abroad). Our office handles a significant part of these cases due to our vast experience in the area.

Acknowledging our expertise, we are very proud to be recommended by different international charities devoted to help parents and other victims of international child abduction, such as Reunite International, MiKK eV (International Mediation Centre for Family Conflict and Child Abduction) and GlobalARRK.

Family and divorce law disputes will always pose difficult challenges to the parties involved, since these disputes relate to the core of their personal lives. Challenging as it may be, it is nevertheless very rewarding to help and advise people when they need it the most, as well as guaranteeing a fair outcome to the children involved.

At Divórcio & Família, the best interests of the children always come first. We try to adopt, as much as possible, a pedagogical attitude towards the parents, encouraging them to make compromises and collaborate with one another in order to protect their child’s interests. After all, their relationship as a couple may have come to an end, but their relationship as parents and educators remains.

Thinking about the need to sensitise other family lawyers to the importance of promoting children’s rights and their harmonious development, as well as the need to offer the skills and knowledge to do so, I also co-founded the Family and Children Lawyers Association (AAFC) on 26 June 2020.

Challenging as it may be, it is nevertheless very rewarding to help and advise people when they need it the most, as well as guaranteeing a fair outcome to the children involved.

Most of the time, a parent seeks legal advice to regulate parental responsibilities based on their own desires: they want to spend more time with their children or, in what seems a necessary consequence, they want the children to spend less time with the other parent. This last claim may even be based on children’s behaviours and reports (for example, reports of abuse or mistreatment).

Of course, the analysis of these behaviours and reports, as well as the expertise to advise on the best model of residence/visitation according to the child’s age, parental relationship dynamics and specific needs, requires scientific knowledge that one does not learn in law school. While the courts consult with the scientific expertise of psychologists and other experts in the decision process, the truth is that such support is not always enough. At the end of the day, the family lawyer’s opinion on the best regime ends up having significant weight in the final decision.

In view of this reality, one of the AAFC’s main goals is to provide our associates the multidisciplinary training deemed crucial for the proper fulfilment of the specific role of the family lawyer. I believe that the offer of these training opportunities is especially important in the Portuguese context, where no specific preparation is legally required to practise family and child law (which I personally find unacceptable) and where credible institutions and courses aimed at the multidisciplinary training of lawyers is very difficult to find – after all, we are talking about areas of expertise as technical and advanced as psychology, paediatrics and child psychiatry, among others.

Our mission, nonetheless, goes beyond specialised training: we aim to bring together all legal professionals who act in this area to promote ethical and deontological values able to guide our professional activity, thus ensuring the promotion of the important interests we are intended to safeguard – those of the children. In the future, we hope this goal leads to an intervention at the legislative level, both through the regulation of family law codes of conduct and through the amendment of family and succession law.

In addition to the ethical obligation of lawyers who take part in family and children court cases to defend children’s best interests, there are also some of us who are called upon to play the role of the child’s lawyer. This prerogative results from the European Convention on the Exercise of Children’s Rights, which recognises the child’s right to be represented by a lawyer in cases where a conflict of interests precludes the parents to represent the child.

[ymal]

Despite the fact that this prerogative is duly regulated in national law, the appointment of a child’s lawyer, either directly by the court or by the child’s and/or the parents’ initiative, is still rare. However, it is a part of an important battery of child participation rights (as is also the child’s right to be consulted and express his or her views in proceedings before a judicial authority affecting him or her), of which the Portuguese magistrates and lawyers are increasingly aware.

In this sense, the child’s hearing in judicial proceedings is increasingly frequent, even when the child is not yet 12 years old. Frankly, this is good news, as it is very important to ensure children do not see the judicial proceedings as an imposition to their life that is totally divorced from their reality, consideration and feelings. It can only be a good thing if children feel safe to participate and be heard, understanding that they can speak their mind truly and without guilt, as the process outcome does not rely on their will, but rather on the safeguarding of their rights.

To minimise the triggering of feelings of anxiety and guilt in the children during the audit, namely the aggravation of loyalty conflicts between parents, our magistrates receive specific training to successfully lead the child’s hearing and work with the assistance and support of other specialised professionals, including psychologists, doctors and social workers. As discussed above, we at the AFFC hope to provide our associates with equivalent training, so that the children may be accompanied at their hearing by their own lawyers.

Nuno Cardoso-Ribeiro, Attorney

Av. Dom João II 35 5E, 1990-083 Lisboa, Portugal

Tel: +351 218 952 028 | +351 924 030 919

Nuno Cardoso-Ribeiro has been a divorce and family lawyer since 2000 and is both co-founder and president of the board of the Portuguese Association of Family Lawyers. He is also a fellow at the International Association of Family Lawyers (IAFL) and a member of the Union International des Avocats (UIA). In addition to authoring multiple articles on divorce and family law, which are regularly published in Portuguese national and regional newspapers, Nuno is also a frequent speaker on family and labour law at a variety of conferences and events. His practice focuses primarily on divorce and child custody cases.

Divórcio & Família is a family and divorce law firm coordinated by Nuno Cardoso-Ribeiro. Its team provides specialised legal support in divorce, asset division, child and custody arrangements, spousal maintenance, family home and inheritance issues, offering a variety of additional globally accessible services in the family and divorce law space.

In this article we hear one such proposal from Mehmet Gün, international lawyer and founder of the Better Justice Association, an independent think tank focused on democracy and rule of law.

The relationship between judges, political leaders and voters is becoming increasingly fraught around the world. In the UK, the recent Queen’s Speech promised to “restore the balance of power between the legislature and the courts” – a move that was promptly branded a “power grab by the state” by some commentators. In the US, public anger against the Supreme Court’s leaked draft of an abortion ruling to overturn a landmark 1973 jurisprudence in the Rove v Wade decision – and President Biden recommending that the Court should not do so – also underlined this year how much the judiciaries have become politicised and how important it is that judges are made properly accountable.

The US Supreme Court has become divided along party lines. Former President Trump went so far as to call judges “so-called” judges and “Obama judges”. In the UK, judges have been accused of being “enemies of the people”. In France, the notorious Outreau Case was described as a “judicial disaster” with the French judiciary accused of shattering lives. In Poland and Hungary, the ruling parties have attempted to remove unfavoured judges and install their loyalists.

In my home country, Turkey, the judiciary has been widely criticised for becoming an instrument in political cases and for hindering dissent with thousands of prosecutions for slandering the president. Similar stories are frequently reported.

The World Justice Project Rule of Law Index recently highlighted that amid attacks from interventionist politicians and populist media, portraying themselves as champions of “the people” against privileged elites, the rule of law around the world is weakening.

As the judiciary is the most vital institution to ensure the survival of a democratic society, it must be continuously protected and nurtured. Judges must be treated appropriately, and it must be ensured that they in turn fulfil their duties efficiently. They must serve society with a top-quality judicial service that is proportionate to the importance of their role as well as the great powers and exceptional privileges provided to them.

As the judiciary is the most vital institution to ensure the survival of a democratic society, it must be continuously protected and nurtured.

Judges are supposed to rule impartially and independently, free from prejudices and outside influence – particularly from politicians. When their rulings are perceived to be politically driven, the judiciary is attacked, with attackers claiming in essence that the judges would rather rule against the will and interests of the society than protect the public. Given that judges are selected and appointed by politicians for their political lenience, is it not natural for their rulings to be or perceived to be politically motivated? When politicians appoint judges, how can the public be sure that the judiciary is independent? Can the public in the US, for example, be expected to be fully satisfied with the ruling of a Republican-majority Supreme Court? A further difficulty here is that human beings are intrinsically political and cannot be expected to be apolitical in all things, with judges being no different.

In addition to politicians’ involvement in the appointment of the judges, there is also a tendency in nations all around the world to allow politicians to interfere with the judiciary. In France, the executive branch is involved in the judicial council (the CSM); in the UK, the Lord Chancellor appoints judges on recommendations by the JAC, and the Venice Commission considers it acceptable for the executive branch to have representatives in the judicial councils. It is obvious that any political involvement in the judiciary will inevitably lead the judiciary to be politicised.

Consequently, the question is: How do we deal with his paradox? Why do the public complain about the political lenience of the judiciary while politicians are mandated to keep the judiciary on a leash?

Public trust in the judiciary is generally higher in better-functioning societies, whereas in societies with less sophisticated and robust civic institutions there are often more complaints about judges. Lower quality of service and accountability leads to the lessening of the public trust in the judiciary and judges. It is obvious that the public are either confused about or have lost trust in their judiciaries.

It is the accountability of the judges that is the main factor which distinguishes judiciaries as being better or worse service providers. It is only natural for the judiciary to be scrutinised, and the combination of free speech and a free press can result in the judiciary serving the people better. In jurisdictions where the judicial office is taken for granted and an opinion holding that accountability compromises judicial independence prevails, it is not surprising that the judicial services lack elements of essential quality. Avoiding accountability for failing to serve the people by hiding behind judicial tenure and purported judicial independence creates a perfect environment for distrust in judiciaries. It is also a perfect environment for justices to rule according to their political agenda, led by loyalty to their appointer.

It is the accountability of the judges that is the main factor which distinguishes judiciaries as being better or worse service providers.

Therefore, it appears that the loss of trust in judiciaries stems from the lack of accountability, and I am convinced that the root of the problem is mainly the lack of accountability combined with a lack of quality of judicial services. It is because of the accountability issues that the people mandate politicians to stand up to judges. Only if the judiciary serves the public properly and is truly accountable will the people support the judiciary and defend it against the politicians. Therefore, to earn and protect its independence, the judiciary must deliver quality services to people and be held accountable for its performance.

The judiciary must be truly accountable to the society that is legitimately entitled to expect its services, not to ruling politicians. Conflating the accountability of the judges with the politicians will seriously compromise the accountability of both, to the extent of conspiring against the very people they serve.

Instead of creating political masters for the judiciary, a unique system of accountability needs to be devised. The judiciary should be regulated by an autonomous regulatory body dealing with all aspects of the judicial service: policy, principles, planning and operations, etc. It should be watertight against even a hint of influence by any individual, group or coalition. It should ensure that the promotion of judges and other service providers is based on their performance in providing quality judicial services, and judicial appointments should be open to all suitable candidates in open transparent competition, which should involve public debate.

Having analysed the issue in depth, we at the Better Justice Association feel that the optimum approach is to establish a Supreme Authority of Justice (“SAoJ”), an independent judicial regulator for quality judicial services. We propose to ensure full accountability of the SAoJ and propose an efficient judicial review of any of its decisions that could be initiated by any member of the public and at no cost. The BJA proposes to establish the Supreme Court of Justice (“SCoJ”) for this purpose.

[ymal]

In summary, the key to protecting judicial independence is focusing on gaining the trust of the people by providing quality judicial service whilst being truly accountable. Securing quality service provision and proper accountability will ensure the judiciary is seen as a friend of the people, rather than a group helping serving themselves – or, even worse, an “enemy” intent on meddling with serious political or social issues. Only then can the public grant full independence to the judiciary – and defend it when it comes under attack.

Mehmet Gün, Founder

Kore Şehitleri Cad. 17, Zincirlikuyu 34394, İstanbul, Turkey

Tel: +90 212 354 00 12

About Mehmet Gün

In a professional career of almost 40 years, Mehmet Gün has developed expertise in commercial and corporate law, life sciences and pharmaceuticals, intellectual property and litigation in Turkey. He has been counted among the pioneers of the development, regulation, promotion and enforcement of modern Turkish IP laws. Most notably, he is committed to promoting greater understanding of the state of the rule of law, in Turkey, the boundaries of the Turkish Judiciary and their effects on the business and social environment. To this end, he has established both the Better Justice Association and Istanbul Arbitration Association NGOs and written a book criticising the abusive use of court-appointed experts by the Turkish judiciary. He is also the author of the book ‘Turkey’s Middle Democracy Issues and How to Solve Them’ and co-author of ‘Turkish Judicial Reform A-Z’.

Antony Sassi and Carmel Green shed some light on the emerging trajectory of the insurance and reinsurance space in Hong Kong, with insights on how the sector has developed in light of the introduction of the new regulator, the COVID-19 pandemic and civil protests.

COVID-19 has inevitably continued to have a major impact on the insurance industry over the past 12 months. In the financial lines sector, we have seen increased exposure for directors and officers as businesses have buckled under ever-growing financial pressures in what has been a challenging economic environment. Insolvencies attract shareholder and creditor scrutiny of management decisions, leaving directors vulnerable to claims. We have seen an uptick in these types of actions. D&O insurers have started to revisit the need for insolvency exclusions in their standard policy forms in order to mitigate potential exposure.

Cyberattacks remain on the rise and COVID-19 has put cybersecurity firmly under the microscope. The global move to remote working, which began as an enforced measure in 2020, has become the norm for many. Greater online – and offsite – activity has presented opportunities for cyber criminals to exploit weakened IT infrastructures and prey on people's vulnerabilities. 2021 was a breakout year for ransomware attacks as sophisticated phishing scams hit more businesses than ever before. Companies with comprehensive cyber insurance have been rewarded, and those without are taking urgent action to plug this gap in cover.

We have also seen a rising demand for crypto insurance. Financial market uncertainty has led to increased demand for crypto products and insureds have looked to hedge associated risks with appropriate insurance. The US continues to lead in this sector, although supply continues to lag behind demand for these products. Understandably, insurers are cautious about pumping capacity into a market that is little understood, given the dearth of data within the crypto sphere and ongoing uncertainty about the regulatory environment.

Insolvencies attract shareholder and creditor scrutiny of management decisions, leaving directors vulnerable to claims.

Another key trend in the insurance market (and others) has been the increased focus on engaging with ESG matters. Insurers are not alone in wanting to promote sustainable, environmentally friendly and inclusive messaging both internally and externally; employees and clients now expect this from corporates as a matter of course. This change in mindset has impacted on the risks that insurers are prepared to underwrite and at what cost. With the fast development of Insurtech, traditional insurers have also been pushed to consider the social sustainability of their products and services.

Against the above, we have seen several changes in the underwriting environment. Insurers have been keen to advance their digital strategies, with use of predictive scoring, pricing and risk selection tools. This has, however, attracted the attention of regulators who are looking to establish clear, ethical rules on the use of big data and AI. There has been a push to ensure that underwriting decisions made by computer and machine learning systems do not contain elements of systematic bias and result in unfair outcomes.

There is no regulatory definition of an insurance contract in Hong Kong, but the concept is the same as under English law: it is the provision of an indemnity/benefit by one party (the insurer) to another (the insured) if an uncertain adverse event occurs, in return for consideration (premium).

For general insurance, the policyholder must have an insurable interest in the subject of the policy (i.e. some economic stake that insurance is capable of protecting) at the time the claim is made.

Although there is no requirement for insurance contracts to be in writing, it is universal practice. The Insurance Ordinance (Cap. 41) (IO) is Hong Kong's primary insurance regulation and lists the different types of insurance business in Schedule 1. Insurance contracts are classified by reference to those classes.

Insurance and reinsurance contracts are subject to the same governing principles. With a contract of reinsurance, the reinsurer is underwriting the risk of another insurer, and so the contract is with the insurer, not the insured. A reinsurance contract might also contain some additional provisions, for example, to the effect that the reinsurer shall have a "right to associate", or "claims control", so that it can closely manage the underlying claim and the potential exposure under the underlying insurance contracts. This will usually depend on how much of the risk is ceded to the reinsurer.

Insurers have been keen to advance their digital strategies, with use of predictive scoring, pricing and risk selection tools.

There are also some regulatory obligations which apply to insurance contracts, but which do not apply to reinsurance contracts, such as in relation to issuing policies.

Since 2017, the Insurance Authority (IA) has been responsible for administering the IO, which provides the legal framework for the regulation of insurers and insurance intermediaries (agents and brokers) in Hong Kong. The IA is a statutory body independent of both the government and the insurance industry. Prior to the IA, the Office of the Commissioner of Insurance regulated the industry for over 30 years. The IA has been given increased powers modelled on those given to the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) under the SFO, which regulates licensed corporations.

The IO was amended in 2019, whereupon the IA became the sole regulator of all insurance intermediaries in Hong Kong, having taken over from the three self-regulatory bodies – namely the IARB, the CIB and the PIBA.

Pursuant to the IO, any person carrying out regulated insurance activities in Hong Kong must be licensed by the IA. Those who are not authorised or exempt risk imprisonment (for individuals) and/or a fine. The IA can inspect, investigate and discipline insurers and intermediaries where it deems a breach has occurred, or if it considers that business has been conducted which is against policyholders’ or the public interest. Insurers and intermediaries in Hong Kong therefore need to ensure they have sufficient internal policies and processes in place, including how to deal with a “knock at the door” by the IA, and maintain proper record keeping.

It is perhaps fair to say the IA has been fairly slow to exercise its powers since it was first established. However, in the last 12 months, we have seen this gradually start to change, with the IA bringing more cases before the Insurance Appeals Tribunal (IAT), a statutory and independent body, and a greater focus on enforcement.

Our clients are long-established multinational insurers, all of whom have substantial experience of adhering to a range of regulatory requirements across a multitude of jurisdictions, and of dealing with local regulators.

This said, the creation of the IA and the enactment of the IO in Hong Kong is very recent (in relative terms) and sweeping changes of this nature inevitably create a degree of upheaval for those involved. Insurers' legal teams have had to familiarise themselves with the new legislation and ensure that their existing policies and procedures comply. Aspects of their business which previously did not warrant scrutiny may do so now. And, of course, the legislation is new and untested, meaning all involved (including the IA) are still in the process of understanding its scope and limitations, where legislation cannot and will not cater for every situation. We are regularly called upon to support our clients as the industry continues to navigate the legislation and understand the extent of its requirements and parameters.

It is perhaps fair to say the IA has been fairly slow to exercise its powers since it was first established. However, in the last 12 months, we have seen this gradually start to change.

Following an investigation, the IA has a wide range of disciplinary actions available to it if an authorised insurer is found guilty of misconduct or an individual is found to be not fit and proper to hold a directorship or controller position. Penalties range from a reprimand (either private or public) to more serious sanctions including a fine of up to HK $10 million (or three times the profit gained or loss avoided as a result of the infringement) or suspension/revocation of the insurer's or individual's licence to carry on insurance business.

Before the IA takes action, the authorised insurer or individual can make written or oral representations and can appeal the IA's decisions to the IAT.

In the last 12 months, the IA has taken disciplinary action against insurers and brokers arising from a range of failings. However, the majority of cases have been matters of serious misconduct e.g. rogue individuals acting alone and for personal gain. The IA has likely been purposefully selective about the cases it has pursued, seeking to make an example of the worst offenders.

Misconduct is obviously not something that we or our clients can prevent absolutely. However, we can support our insurer and broker clients to ensure they have the correct infrastructure in place to help catch individual behaviours that fall foul of the rules. For other types of (unintentional) breaches, we can support them in developing policies and procedures that reflect the requirements of the regulations to ensure that all involved are aware of their respective obligations and are operating in compliance with the rules. If breaches occur, we can advise on how to manage and respond to the enquiry and the benefits of early and voluntary cooperation.

We have always maintained a wide practice area. However, certain local and global events over the last few years have generated some highly complex and sensitive instructions which have been a privilege to work on.

The Hong Kong protests, which took place throughout 2019, are a key example. We provided specialist support to a number of key insurers in respect of a ream of large property damage and business interruption claims after a range of corporations and business suffered significant losses during the protests. These claims required us to consider (among other things) the application and interpretation of terrorism exclusions, a policy provision which is rarely engaged. In circumstances where the protests were the first of its kind in Hong Kong, and given the lack of legal authority on the issues arising, we were able to provide highly specialised legal support and innovative commercial solutions to assist our insurer clients. Our work led us to team up with various esteemed London insurance QCs, which demonstrates the magnitude and significance of these claims.

The creation of the IA and the enactment of the IO in Hong Kong is very recent (in relative terms) and sweeping changes of this nature inevitably create a degree of upheaval for those involved.

In the cyber risks sphere, over the last two years we have advised on policy coverage in respect of some of the largest, most high-profile ransomware attacks affecting HK companies. We also act as the regional breach solution for a major leading international insurer. Our product, ReSecure, which is written into the insured's cyber policy, includes a dedicated 24/7 hotline which an insured can call in the event of a data breach to obtain immediate crisis response. We provide breach coordination and legal advice, including as to data privacy issues, regulatory reporting and notification to data subjects; we also partner with digital forensic and PR firms to deal with the full suite of technical and PR aspects arising from the breach. And, of course, we work with the insurer to comply with the necessary reporting requirements under the policy.

While COVID-19 is still present, we can expect it to have a reduced impact on the insurance market in the coming 12 months. Despite a likely lingering feeling of uncertainty for the remainder of this year, financial commentators – including Deloitte – are reporting accelerated growth in Asia. With lockdowns and international travel restrictions gradually lifting, demand for personal accident and health insurance, which makes up the largest part of general insurance in Hong Kong, is set to rise.

In the liability market, we expect to see the most growth in cyber insurance. As mentioned above, cyber policies have come into their own in the past two years and demand is continuing to rise. We also expect the trend for increased financial fraud cases and risks of insolvency to continue, which keep up demand for D&O insurance.

A key interesting area of growth for the D&O / IPO insurance market is in the form of SPACs, or "blank cheque" companies. These are newly formed shell corporations listed on a stock exchange for the sole purpose of acquiring or merging with one or more target private operating companies. This enables the private company to go public more quickly, without going through the traditional IPO process. As an IPO will usually give rise to a "change in risk", it is usually appropriate to take out a specific IPO / POSI policy to protect against the specific risks associated with IPO transactions, serving to ring-fence the exposure away from a company's conventional D&O programme.

[ymal]

Given the low cost of SPACs, we can expect their popularity to rise and for Asian exchanges to want in on the action. While a SPAC listing is similar to a reverse merger, which we know from experience have capacity to generate claims, there are key differences from a risk evaluation perspective. In an ever-hardening market, SPAC IPO D&O insurance is hard to come by and carries hefty premiums. This is increasingly flagged as a risk in prospectuses, especially by the larger sponsors. High premiums are of course common to new products where insurers lack sufficient historical data to assess risks.

There are also considerations specific to this product which stand to affect premium: the "blank cheque" quality is difficult to model in underwriting; there is uncertainty of where the trust's capital will be deployed, and carriers may not be able to issue long-term policies in accordance with reinsurance treaties. Underwriters placing these risks can therefore be expected to give due consideration to a range of factors, including: (i) the background and reputation of the sponsor; (ii) the amount of capital being raised; (iii) the target class of business; (iv) the location of the target business; (v) the specifics provided in the registration filings, and (vi) the quality of the team of professionals advising on the transaction.

Antony Sassi, Managing Partner

Carmel Green, Partner

38/F One Taikoo Place, 979 King's Road, Quarry Bay, Hong Kong

Tel: +852 2216-7101 | +852 2216-7112

12 Marina Boulevard, #38-04 Marina Bay Financial Centre, Tower 3, Singapore 018982

Tel: +65 6422-3000

Fax: +65 6422-3099

E: antony.sassi@rpc.com.hk | carmel.green@rpc.com.hk

Antony Sassi is managing partner at RPC’s Hong Kong Asia practice and a leading litigator in the Hong Kong market, with a focus on defending professionals and D&Os relating to various tortious and contractual claims and advising more broadly on financial lines related matters. He is President of the HK Insurance Law Association and sits on the Law Society Insurance Committee, and has handled some of the largest claims in Asia over the last few years against various professionals. He has also been ranked in Band 1 for leading individuals in Chambers Asia since 2011.

Carmel Green is an insurance lawyer specialising in financial lines and professional indemnity matters, with particular experience in handling large-scale insurance-related disputes and advisory work. She is regularly instructed by insurers to review, approve and draft insurance policy wordings across various lines of insurance business. Carmel has been ranked as a leading individual in Chambers Asia since 2017.

RPC is a global corporate and insurance law firm founded in London in 1898. It has been named Law Firm of the Year three times since 2014, and Best Legal Adviser every year since 2009. RPC’s team of 750 is recognised as industry-leading in insurance, retail, media, tech and numerous others.

Recent years have seen the introduction of sweeping legislation aimed at increasing oversight of mining ventures, leading in turn to a wave of new compliance considerations. In this interview with Darryl Levitt, we discuss the regulatory space in the mining industry and how counsel can expect to see it evolve throughout this coming decade.

Currently, mining in Canada is subject to significant regulatory disclosure requirements. To begin with, there are minimum standards for disclosure of technical information incorporating the Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy, and Petroleum (CIM) standards. National Instrument 43-101 sets out minimum standards for disclosure of technical information. The Companion Policy and CIM Best Practice Guidelines should also be followed where possible. The qualified person (QP) preparing the technical disclosure, based on his/her relevant experience and professional judgement is responsible for choosing the assumptions, methods, and practices used to verify, interpret, estimate and report technical information. Given that exploration and mining companies will require access to large amounts of capital over a lengthy period, there is a need for regulators to control and deal with potentially misleading information in order to protect investors.

Further, under Canadian securities regulations, public companies must disclose information material to investor decision-making. This would include material environmental matters associated with activities affecting climate change. Based on the latest federal budget, Canada’s financial regulator OSFI will require federally regulated financial institutions such as banks, insurance companies and federally incorporated or registered trust and loan companies to publish climate disclosures aligned with the Taskforce on the Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) framework commencing in 2024 and employing a “phased-in” approach. While the rules do not yet apply to non-financial institutions, OSFI will expect the financial institutions to collect and evaluate information on climate risks and emissions from their clients (including mining and oil gas clients). The government has stated that it is committed to moving towards mandatory TCFD reporting “across a broad spectrum of the Canadian economy” and that it also expects to require ESG disclosures from federally regulated pension plans.

In jurisdictions with extensive mining activities such as Australia, Canada and South Africa, mandatory technical disclosure requirements, whilst not identical, are mostly similar in substance with similar objectives. Other aspects of disclosure, such as best practices on climate-related and ESG disclosure, have their unique differences.

Under Canadian securities regulations, public companies must disclose information material to investor decision-making.

For example, on 21 March 2022, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) introduced proposed rules for climate change disclosure requirements for both US public companies and foreign private issuers. In March 2022, the SEC proposed mandated corporate reporting on climate change by public companies. These disclosure requirements are mostly prescriptive rather than best practices and are largely based upon the TCFD reporting framework and the Greenhouse Gas Protocol.

SEC filers would be required to disclose their Scope 1 and Scope 2 greenhouse gas emissions, which are those emissions that “result directly or indirectly from facilities owned or activities controlled by a registrant.” The proposals would compel issuers listed on an American stock exchange to report the entire extent of their CO2 emissions, in contrast to recent Canadian proposals by the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) that would permit companies to opt out of full greenhouse gas disclosure. The proposed SEC rules are expected to be finalised later this year.

The United Kingdom and New Zealand are also now proposing mandatory climate-related disclosures.

There is a global trend to harmonise best practices in areas that affect common interest issues around the world. The relevant areas would be relating to disclosures around ESG, climate change, sustainable and responsible mining processes, inclusivity and diversity of management, transparency of ownership and transparency of indigenous consultation. Although some disclosure requirements are only best practices and voluntary in many respects, we are seeing a drive to transform these best practices into mandatory disclosure requirements in many jurisdictions. The growing awareness of factors considered by some to influence climate change has resulted in a concerted effort by lobbyists, various industry participants and NGOs to transform best practices into mandatory compliance with calls for enhanced levels of disclosures.

By far the most common compliance issues we have observed are deficiencies in technical report content relating to estimates of mineral resource, the disclosure of estimates and a lack of compliance with Part 3 of NI 43-101 – such as omissions by the QP to describe the proposed mining methods – and failure by the QP to specify the means of verifying data.

Certain other routine disclosure in websites, AIFs, news releases and other public disclosure has often failed to state both the tonnage and grades of mineral resources or mineral reserves, whether the mineral reserves were included or excluded from the mineral resource estimates or included in general risk disclosure that was not specific to the company’s mineral project.

There is a global trend to harmonise best practices in areas that affect common interest issues around the world.

It is necessary to seek appropriate advice from knowledgeable and experienced technical, compliance, ESG, and legal experts to avoid missteps that can be very costly and difficult to rectify if overlooked. Get to understand what disclosure is mandatory and what is voluntary. Adopt best practices where possible.

The COVID-19 pandemic has altered how we work and impacted both digitisation and the heightened need to integrate ESG commitments into corporate mining operations. The single biggest underlying driver and opportunity for transformation lies in the green energy transition and how companies can make use of this trend to change with the times. There is a growing body of laws, policies and treatises being developed to assist companies to align capital to ESG compliance and disclosure, implementing ESG into the organisation, reshaping traditional value chains and shifting towards more effective community and indigenous relations.

Momentum is also growing towards the development of a body of law, rules, best practices and guidelines to prepare operations for climate change and ensure compliance with applicable laws. A developing trend by governments and regulators in advanced economies is the requirement for more stringent disclosures that identify ultimate beneficial ownership of interests in mining companies, thereby ensuring compliance with sanctions imposed against adversarial countries and sanctioned individuals. Finally, with more devices being connected, some of the industry’s biggest cyber vulnerabilities are around operational security issues. We see a legal trend developing towards closing the vulnerability gap between IT and OT cybersecurity concerns.

We foresee continued interest in the development of battery metals and energy materials projects like lithium and uranium, what we call the “green metals”. We also predict a continued challenging mining financing environment for base and precious metals exploration. The need to secure new sources of materials for the energy transition amid sanctions and concerns around a possible broader European conflict has increased the tolerance for investment in perceived riskier jurisdictions in Africa. There is also a risk that over-zealous mandatory compliance requirements may backfire and lead to choking out the emergence of some new mines. There are signs of rich countries' rising concern about securing sufficient supply, and companies and investors are considering projects they may have previously overlooked, while governments are also looking to Africa, anxious to ensure their countries can procure enough metals to feed an accelerating net-zero push.

Get to understand what disclosure is mandatory and what is voluntary. Adopt best practices where possible.

In addition, we foresee a developing trend of alternative energy companies engaging with mining companies to collaborate on green and alternative energy projects on-site in order to reduce reliance on carbon-intensive fossil fuel sources for powering mining operations. We anticipate that governments will offer more grants to alternative energy project developers in an effort to achieve net-zero economies. The 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), held in Glasgow in November, highlighted the mining industry’s integral role in supplying the metals and materials critical for a low-carbon future. The way in which mining companies position themselves today in preparation for this change will determine their sustainability and could make or break their competitive advantage over the next decade.

Africa will soon feature more prominently with analysts and investors. Africa is still fraught with security risks of militant activity in the Sahel region, but the continent is looking increasingly attractive given the geopolitical crises unfolding in Eastern Europe, Asia and the Middle East.

Valuable extractive commodities are often located in high-conflict zones and jurisdictions where government regimes frequently change, or are located in places with despotic governments. The rapid technological changes occurring currently in the EV space and the battery sector have led to a rush to secure future supply of battery metals for exploitation. Protecting a company’s investment is just as important as determining how profitable it could be if materials were viably extracted. It would therefore be incumbent for the legal practitioner to research intensively and understand what types of sovereign guarantees might be available to protect an investment, whether the host country is a signatory to any international convention on mediation and arbitration, the credit rating of the host country and the relative ease with which one can advance projects from mineral evaluation to extraction.

Given the current insatiable demand for battery metals, it is possible that in the event a massive discovery is made, that the project may be deemed a strategic asset and perhaps expropriated. It would be prudent to recognise this legal risk and mitigate it where possible. Having worked on projects in some of the most difficult jurisdictions across the globe, we also see the potential for the rise of resource nationalism when dealing with countries that host commodities that are classified as critical metals. Maintaining favourable working relations with the government and engaging effectively with the local communities where mining activities will be conducted will go a long way to ensure a lasting tenure. Local beneficiation is also a factor to consider implementing into the plans of the mining operation.

The need to secure new sources of materials for the energy transition amid sanctions and concerns around a possible broader European conflict has increased the tolerance for investment in perceived riskier jurisdictions in Africa.

The push for enhanced transparency and disclosure does not fall squarely on the shoulders of mining companies. Certain countries, particularly in Africa, have embraced technological advancements to offer better transparency to investors on permitting status processes for applicants. This has resulted in improved investor confidence in the sector and the reduction of the potential for cronyism in the award of lucrative mining permits.