We speak to John Douse, a previous Lawyer Monthly Forensic Expert of the Year, all about forensic investigations. He discusses the advancements that have occurred in his line of work, the developments which are yet to occur for the betterment of his field, and if there is enough interest motivating future generations to continue progressing this very vital area of investigative work for the legal sphere and beyond.

How have you seen forensic investigations develop so far over your years of expertise?

Technological advances (e.g. UHPLC MS-MS and DNA 17 techniques) and associated enhanced quality control procedures have immeasurably improved many areas of forensic casework, thus enhancing the reliability of forensic findings.

However, a trend has recently become established where routine forensic services, and hence forensic expert opinion, appear to have become too expensive to be used in increasing numbers of routine criminal investigations, due to austerity.

As a result of this, some scientific areas are reported to have become devoid of any forensic input entirely, resulting in clashes of opinion between forensic scientists and lay persons who have no significant forensic scientific training or understanding.

Such inappropriate expression of opinions, by such individuals, outside of their areas of expertise, (caused by financial circumstances entirely beyond their control), has led to them having to suffer various levels of professional embarrassment including exclusion from trials, with their place as prosecution experts ordered by the Judiciary to be taken by defence experts.

Additionally, lay persons have begun to be used to prepare statements for the Court in complex specialist areas, e.g. using Wikipedia as an information source, and sometimes, but not always, with the written recommendation at the end of the report, that if expert opinion is required, then it should be sought elsewhere.

Correction of inaccurate conclusions, so arising, by the defence, causes repeated and understandable great upset to those responsible for overseeing prosecutions, resulting again in significant professional embarrassment for such individuals when other scientific experts confirm the defence findings.

Sampling of exhibits at scenes, by trained personnel, also, (for the same reasons of necessary financial expediency), has now, not infrequently, replaced the process of simply bagging exhibits and sending them to be processed in forensic clean room facilities.

Such situations may then have to be corrected by the expensive preparation of further reports and also, not infrequently, through intervention by the Judiciary.

Examples of lay persons attempting forensic procedures have also been encountered, (again as a result of agencies desperately trying to balance inadequate budgets), one such involving the weighing of small drug samples, which illustrates the misunderstandings that can occur even in such a seemingly simple forensic procedure. Thus, a series of such samples were found to have been weighed using a set of inaccurate kitchen scales seized in another case; with the explanation that this method of weighing was likely to give a more representative indication of the weights of the samples, because it employed the method and equipment used by drug dealers, as would be likely to be encountered on the “street”.

Sampling of exhibits at scenes, by trained personnel, also, (for the same reasons of necessary financial expediency), has now, not infrequently, replaced the process of simply bagging exhibits and sending them to be processed in forensic clean room facilities.

This has the potential to result in the possible loss of evidence, e.g. when samples are simply taken from multiple areas before laboratory submission, (rather than providing the option of samples from each area being available for analysis if required, and combination of samples being a laboratory option), or may even involve possible compromise if sampled in potentially contaminated areas.

Another example of the different and alternative logic of lay individuals was found to have involved an individual who suffered from Type 1 Diabetes being given the responsibility for the exhibits in a case involving suspected insulin poisoning.

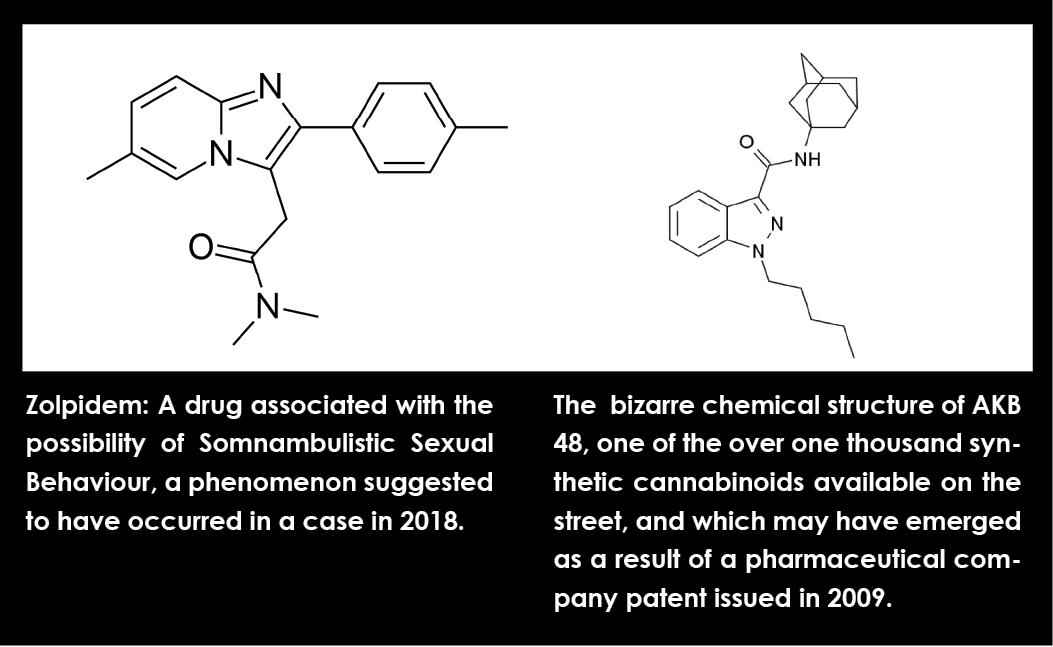

A further example is the practice of experienced lay individuals identifying samples of cannabis simply by appearance, and which at one time was a potentially acceptable method in some cases. The concern, now, is due to the increasingly encountered practice of the attempted substitution of cannabis samples with herbal material and possibly poor-quality cannabis, sprayed with solutions of synthetic cannabinoids. (This represents the classic example of the problem of the continuously changing forensic environment). Discrimination of these types of samples should be noted to require the use of sophisticated laboratory analysis.

The critical importance of thorough defence investigations in all casework, including analysis and consideration of the circumstantial evidence, rather than just the work of a few hours consideration of a limited assessment of the case and the forensic analytical results, should be noted.

Similar issues are also being encountered where lay persons are required to decide (on the likely grounds of economy) which exhibits are of significance and should be sent to forensic laboratories, and which parts of alleged victim medical records should be released to the defence.

Thus in 2018 in a case involving explosives, at the defence inspection of exhibits, (which had been described as being of no explosives significance), inspection revealed one item, the nature of which resulted in all serious Section 58 charges, being able to be dropped and the defendant receiving a fireworks ASBO!

The critical importance of thorough defence investigations in all casework, including analysis and consideration of the circumstantial evidence, rather than just the work of a few hours consideration of a limited assessment of the case and the forensic analytical results, should be noted.

One example of this was the result of pro-bono analysis of 3000 pages of a casefile, (due to issues with prior authority), and where, in the case of death by perforation of the bowel by an overlooked rectally inserted object, (which was claimed to have been inserted with violence), an adverse side-effect of a prescribed common antidepressant was uncovered which indicated its ability to relax the internal anal sphincter.

Ever increasing use of high definition video surveillance has been observed to have defined sequences of sequential contact in some DNA cases so precisely and accurately that they almost resemble laboratory trials in their precision.

Such video surveillance techniques, along with cell phone analysis procedures, documenting the circumstances of incidents, continually are found to increase the ability of the Court to interpret the exact nature of the situations in cases involving the question of consent or ability to give consent.

The use of the new DNA-17 methodology has produced significant improvements in sensitivity, but this has increased the likelihood of detecting secondary and even higher forms of transfer, and that can raise sufficient doubt to significantly affect case outcomes.

The use of DNA deconvolution software has been, as yet, somewhat disappointing in its ability to only confirm, but with a higher level of reliability, what can be observed in DNA analytical profiles.

In the case of forensic trace analysis, significant forward progress has been made, however over-reliance solely on the new techniques, has lost the power of the older methods in being able to screen highly contaminated real-life samples for vast numbers (and thereby possibly even the complete range) of possible suspect compounds.

Thus, reliance on the new mass spectroscopy methods (e.g. UHPLC MS-MS) has made the mass screening of samples possible for numbers of the most common drugs that the instrument has been set to determine, however the drawback is that the instruments will, not infrequently, only produce results in regard of the compounds that the instrument has been requested to screen for.

In contrast, the fundamental forensic challenge in all types of analytical cases lies in being able to routinely screen samples for complete ranges of compounds, with an emphasis on the unusual and rare examples that not-infrequently are encountered.

Thus, at present even in the latest most modern (2018) published example of UHPLC MS-MS analysis, (with Multi Reaction Monitoring), only 80 synthetic cannabinoids can be simultaneously screened for, out of over 1000 possible such compounds.

In 2019 it has been noted that application for the funding for such exhaustive and thorough investigations is now having to be refused, (due to austerity), and other experts are having to become engaged in a commercially driven “race to the bottom”

The selective detectors once used for this purpose appear to have been overlooked, for example the use of the picogram sensitive TEA Nitrogen specific detector, which has the potential to be applicable to the simultaneous screening of body fluids for traces of the thousand or so synthetic cannabinoids, and also the sulphur and phosphorus photometric selective detectors for chemical warfare agents, (using confirmation by mass spectroscopy).

The use of such “techniques of a past era” have the potential to achieve considerable potential economies due to their relative lower cost and also avoiding the need for using the more expensive techniques for every sample.

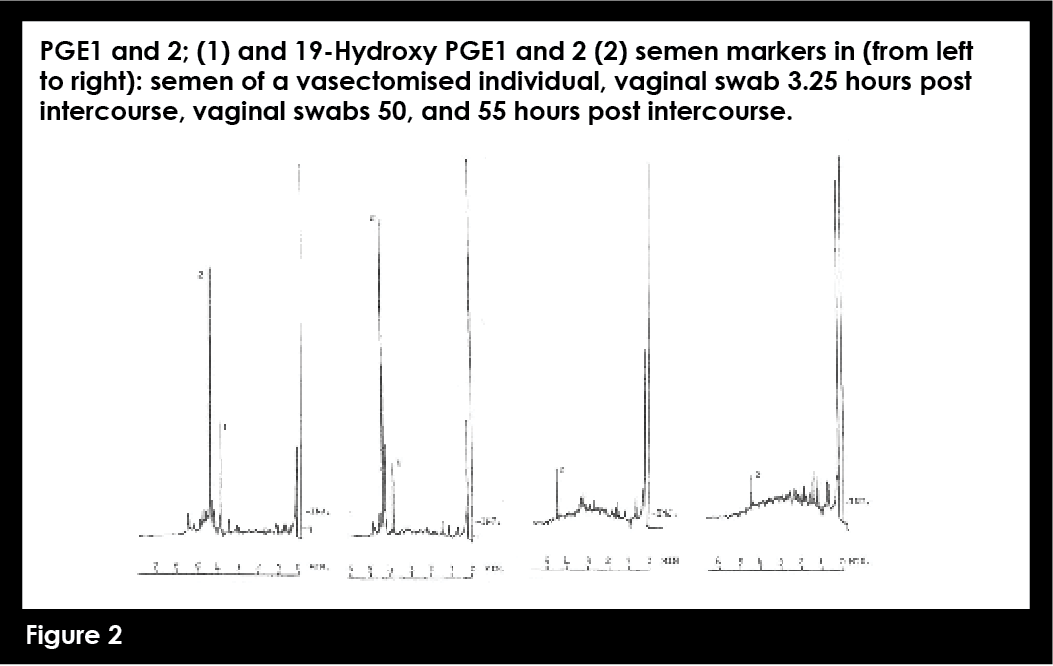

The use of “dilute and shoot” techniques (where samples are simply diluted with minimum processing prior to analysis), combined with MS-MS multiple reaction monitoring has greatly simplified the trace analysis of the most likely to be encountered compounds in forensic samples. It is noted that such methods might be usefully used to revive older methods, that, despite having great potential were impractical due to the complexity of analysis. Thus, an example of a screening method for a range of prostaglandin markers present at very high levels in semen (including vasectomised individuals) may now be amenable to the new dilute and shoot methods. (Figure 2) (JMF Douse, J Chromatography, 1985, (348) page 111).

Similarly the use of the old simple solid phase clean-up methods (e.g. using XAD polymers, or bonded silica materials, now available sealed into Eppendorf type micro pipette tips, for facile use) can result in dramatic improvements in ultralow level trace analyses; this is especially useful when trying to detect very low levels of analytes in limited, real life, heavily contaminated samples, and where resort is often made using only multiple reaction monitoring to achieve selectivity, (e.g. as in a case of fentanyl compounds present in residues on clothing from a hostage situation).

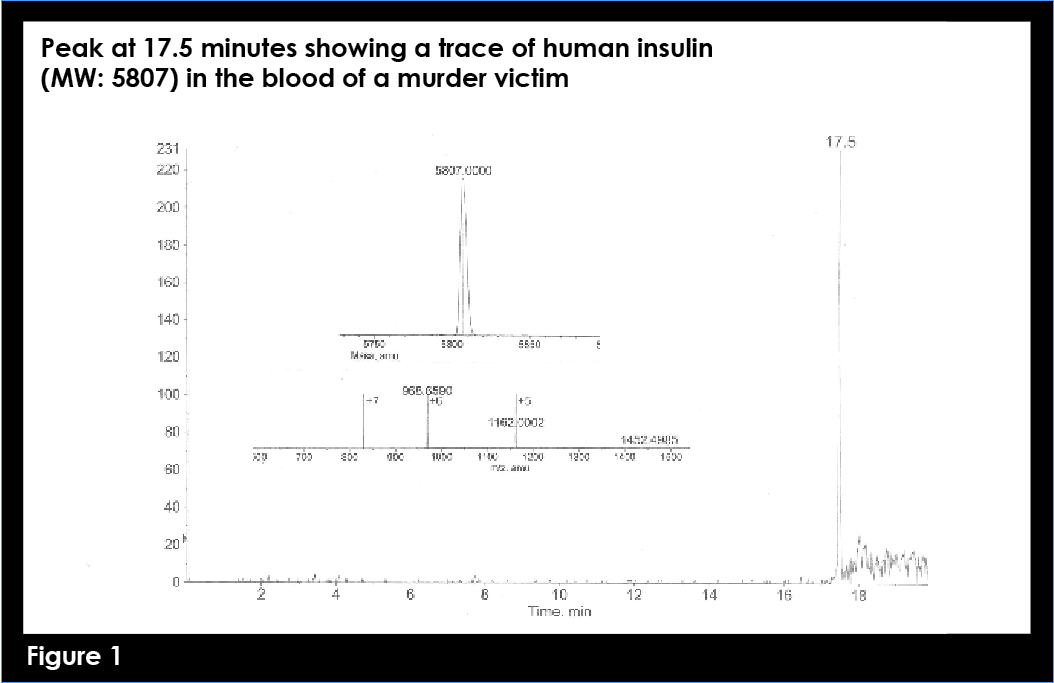

An example of the first ever method (2007) for the detection of human insulin at the low nanogram level in a forensic sample of the dried blood of a suspected poisoning victim, carried out by UHPLC Q-TOF MS MS using a simple C-8 bonded silica clean up technique, is shown in figure 2.

It should be noted that all toxicological cases could potentially be greatly assisted if those who suspect that they have been drugged, or their respective carers, could: at the earliest opportunity get responsible witnesses (ambulance or police personnel) to supervise the process of simply emptying out the contents of an unopened soft drinks bottle (with a previously unbroken seal if no proper collecting vessel is available), and collect as much urine as possible for submission, both noting the time of collection, and also recording the entire procedure on mobile phones (clothing being retained as an exhibit).

What has been the biggest advancement in your line of work so far and how did it impact your role as an expert witness?

The ability, as a defence expert, pre-trial, to access every exhibit and aspect of the evidence in cases, and to be able to create as accurate as possible a chronology of events; allowing the forensic evidence to be thoroughly considered in relation to this, permitting any further resulting investigations to be identified and performed, and conclusions drawn.

This procedure allows aspects of the case that would otherwise be overlooked to be investigated pretrial. The issue with this approach is that it is very time consuming, and taxes the human intellect to its limit, resulting in its likely application to only a relatively small proportion of all cases.

In 2019 it has been noted that application for the funding for such exhaustive and thorough investigations is now having to be refused, (due to austerity), and other experts are having to become engaged in a commercially driven “race to the bottom”, e.g. through gaining instructions by submitting ever lower quotes, and that even leaves out ever more of the critical aspects of the forensic process, such as the defence examination of exhibits (travel to prosecution forensic laboratories having now become deemed to have become too expensive).

The world wide web needs to employ a procedure such as “refresh annually or perish”, to all uploads due to the current overload with material which is either irrelevant, or outdated and hence of no use, in order to simplify searches (with material failing this requirement consigned to a separate remote archive).

However, it is noted that it may be possible that in the future, techniques based on artificial intelligence might be capable of development in order to allow such a thorough approach to be applied to all cases, assuming that total disclosure of all available evidence was possible, and with such findings being confirmed by human experts.

The ability to access the entire, and very latest, peer reviewed scientific research literature has very recently experienced a seismic shift in efficiency, due to the establishment of the phenomenon of “Open Access” publishing.

An example of the power of this resource continues to be demonstrated in a 2018 firearms residue case, and where two critical research papers were published online, (describing a novel source of tin shotgun residue), just one day before the defence report was due to be completed.

The power of high definition total CCTV coverage of all public places as always reigns supreme, for example, allowing even the nature of social interactions to be examined by the Court and Jury as a result of, for example, the consideration of facial expressions.

You previously stated that the development of the World Wide Web has been one of the most influential resources that has assisted in the analysis of forensic casework. Can you share what you think the next development may be?

A most critical development has just recently occurred, and where the global research community has confronted, en masse, the publishers of Journals containing peer reviewed scientific research papers, in regard of the need to purchase expensive access, (circa £40 per paper), post publication, in order to be able to read the full content.

This extraordinary, and indeed epic confrontation, involving almost the entire world wide research community threatening to withdraw all submission of publications to the established publishers, has resulted in the phenomenon of “open access” publication, where research grants are preloaded with funds to compensate publishers, allowing global free access to the contents of the latest research papers in their full entirety.

This has resulted in a much more facile ability to exhaustively search the exponentially ever-increasing peer reviewed scientific literature, unlimited by cost, and which previously had complicated search procedures.

The world wide web needs to employ a procedure such as “refresh annually or perish”, to all uploads due to the current overload with material which is either irrelevant, or outdated and hence of no use, in order to simplify searches (with material failing this requirement consigned to a separate remote archive).

Thus, forensic experts have to, on a routine basis, consider the best ways to carry out illegal practices such as poisonings, and also those forensic scientists who have held responsibility for laboratory development have been required to consider all possible (including the most unlikely) “101” methods likely to be encountered.

Further to this in what ways should developments be made in order to ensure forensic investigations are as refined and accurate as can be?

The requirement for experts to prepare a list of all points of agreement and disagreement prior to trial should be made mandatory, and a process that cannot be avoided, at the cost of the case being dismissed if this procedure is avoided or bypassed.

It is quite common, that during this procedure, logical consideration of scientific principles has the result of significant agreement being obtained in a joint statement, and which situation assists the Court greatly.

Some individuals and laboratories are noted to be reluctant to attend such meetings, preferring to engage in the combative approach, but this usually results in the prosecution legal team being forced to discard their expert reports.

Legal aid should be re-instigated in all cases, thus allowing the principal of equal arms always to be complied with, and which fails when the costs of forensic investigations become apparent, and which are usually unable to be financed once other legal fees have been addressed.

Immunity from suit should be re-instigated for all forensic experts. This would permit experts to be able to address all types of cases, instead of having to consider exclusion of cases, such as extremely fraught and complex issues where very high personal damage claims are sought.

The need for such a recommendation is recent, as it has become apparent that the professional liability insurance policy of an expert increasingly appears to be in danger of becoming routinely considered to be a viable means of achieving compensation if all else fails.

As suggested, at previous times, those involved in major incident control and subsequent investigation should utilise the services of an appropriate forensic scientist in order to assist with correlation of all information and evidence, and to assist in interpretation. The reason for this suggestion is that while conventional experts are used to the precisely defined conditions of the laboratory, forensic experts deal routinely with the complex interface where science encounters the real world.

Thus, forensic experts have to, on a routine basis, consider the best ways to carry out illegal practices such as poisonings, and also those forensic scientists who have held responsibility for laboratory development have been required to consider all possible (including the most unlikely) “101” methods likely to be encountered. Thus, it was immediately clear to forensically trained scientists, from a simple consideration of the scenario, that it was likely that a discarded applicator in the form of a likely highly attractive and expensive innocent looking object, would be likely to have to have been discarded following use of such an object to dispense a toxic agent.

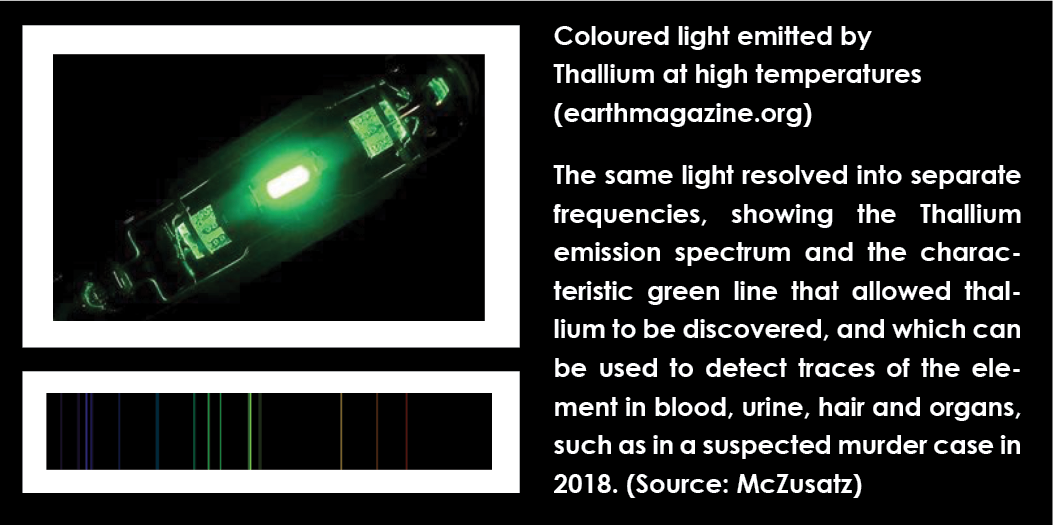

It is noted that there is an urgent need for hospitals to have routine access to advanced mass spectroscopic methods, for urgent, prompt, and immediate screening of body fluid samples for traces of toxic heavy metals, especially thallium, thus avoiding the possibility of the development of serious internal organ damage due to the commonly encountered phenomenon of very delayed and even missed diagnosis (as was encountered in a murder case in 2018).

Can you expand the impact of a lack of development in such areas has on your work, and in cases you address in Court?

This lack of development usually adversely affects the prosecution case and facilitates the task of the defence. However, it should be noted that the defence has a duty to highlight such deficiencies and it should be noted that such necessary impartiality has been demonstrated in the preparation of this article.

The overarching forensic laboratory quality control protocols should be able to be relaxed in a controlled fashion, under special circumstances, in order to allow rapid new method development, for specific analytical applications mid case.

An example of this phenomenon is noted in a 2007 case (R v Campbell Norris) where the defence rapidly developed a new, (and indeed the first), UHPLC Q-TOF MS-MS method for detecting and identifying low levels of Insulin in blood mid trial (Figure 2) thus not only assisting the trial, (where all the other experts had failed), but also contributing to a breakthrough in such work.

For some time, great interest has been fuelled by the popularity of TV crime investigation programmes, and which situation has encouraged many young people to consider a career in forensic science.

Moreover, on the other hand, can you share your ideal projection of the future forensic investigative sector?

If a healthy developing sector is required then the permission, (and funding), for defence experts to be able to rigorously test prosecution findings must remain. This requirement has become even more important as the austerity driven financial cuts reduce the efficiency of the prosecution investigations.

By this means a process of continual improvement can be maintained as the forensic environment continually changes (very similar in regard of forensic analytical approaches to the principle of “Natural Selection”).

The application of such thorough defence investigations also has the obviously beneficial additional effect of revealing situations where legal definitions of criminal offences are lacking in appropriate scientific specification.

For example, there being no specified maximum threshold level of alcohol in blood for defining the situation of a mother being found to be intoxicated in charge of a minor (as encountered in a case in 2018).

A similar such observation, that has been already mentioned in this article, is the situation of cannabis samples being allowed to be identified as such with no forensic analysis; a situation now potentially compromised by the practice of the passing off as cannabis, of herbal material, and possibly also poor quality cannabis, sprayed with solutions of synthetic cannabinoids.

Are there any reasons why development is yet to be made?

Two reasons have been identified and these are: the lack of adequate funding in one of the richest countries in the world, and the historical break in the continuity of forensic experience when the Forensic Science Service was replaced by commercial operators, and which has, even now, to be continuously remedied.

Is there enough interest in the future generations in your line of work?

For some time, great interest has been fuelled by the popularity of TV crime investigation programmes, and which situation has encouraged many young people to consider a career in forensic science.

However, it should be noted that a critical requirement for becoming a forensic expert previously (1979) was a degree in an academically rigorous subject, the most useful being chemistry.

This test of academic rigour is vital preparation for coping with the extreme demands of the interpretation of complex cases, and ability to rapidly and flexibly respond to changes such as the late introduction of new evidence, when under extreme time pressures.

A PhD in such a demanding academic scientific subject is critical if the ability to develop “in house” new improved forensic techniques is to occur.

It should be noted that one of the key requirements of a forensic laboratory involved in casework used to be the ability, if required, to rapidly develop and sufficiently accredit novel techniques to address urgent analytical challenges e.g. mid case or even mid trial.

However, with the institution of strict and unyielding quality control procedures no capacity appears to be currently available for such improvisation.

Such rapid developments have included overnight enhancement of an explosive analytical technique in order to be sure to be able to disprove a positive screening result, at a hotel where the entire government cabinet had been evacuated.

Another example was the development and demonstration of a novel analytical technique (including clean-up) in 36 hours (with the distraction of being required to attend Court unexpectedly mid process), capable of successfully detecting and distinguishing nanogram levels of insulin variants in human blood, during the investigation of a case of human insulin poisoning. (R v Campbell Norris) (see figure 1).