The man killed by federal agents in Minneapolis on Saturday has now been identified as Alex Pretti, a 37-year-old intensive care nurse whose death has intensified scrutiny of the Trump administration’s immigration enforcement surge and the use of lethal force on American streets.

Pretti was shot during a chaotic encounter involving multiple federal agents near 26th Street and Nicollet Avenue in south Minneapolis. Video footage circulating online shows him being wrestled to the ground by several masked officers before gunfire erupts. Federal officials say he was armed and “violently resisted” efforts to disarm him — a claim that Minnesota state officials have publicly challenged after reviewing video evidence.

The killing marked the third shooting involving federal agents in Minneapolis this month, following the death of Renée Good earlier in January and another non-fatal incident days later.

According to his parents and colleagues, Pretti worked as a registered nurse in the intensive care unit at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System. He attended nursing school at the University of Minnesota and had also assisted on scientific research projects earlier in his career.

Dimitri Drekonja, chief of infectious diseases at the VA hospital and a professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota, described Pretti as an “outstanding” nurse who was deeply committed to patient care.

“He wanted to help people,” Drekonja said, describing him as kind, hardworking, and quick with humour. “He was always asking what he could do to help.”

Pretti obtained his nursing licence in 2021, which remained active through 2026. Colleagues said he was respected for his work ethic and his willingness to step in when others needed support.

Family members told the Associated Press that Pretti had been upset by the expanding federal immigration operations in Minneapolis and had participated in protests following the killing of Renée Good earlier this month.

“He cared about people deeply,” his father, Michael Pretti, said. “He felt that protesting was a way to express that care.”

Videos from the scene appear to show Pretti directing traffic, filming federal agents on his phone, and intervening when a legal observer was shoved to the ground. In one sequence, he is sprayed with a chemical agent before being tackled by officers. As at least five agents surround him on the ground, shots are fired at close range.

Minnesota police later said Pretti’s only known prior interactions with law enforcement involved traffic violations. Police Chief Brian O’Hara also stated that Pretti was a lawful gun owner with a permit to carry.

The Department of Homeland Security has maintained that agents fired “defensive shots” after Pretti approached officers with a handgun and resisted disarmament. Border Patrol commander Gregory Bovino claimed the shooting prevented a potential “massacre” of law enforcement.

Minnesota Governor Tim Walz rejected that account after reviewing video footage, calling the federal narrative “nonsense” and “lies.” He said the federal government could not be trusted to investigate itself and insisted the state would conduct its own inquiry.

Minnesota’s Bureau of Criminal Apprehension has since said its investigators were initially blocked by DHS personnel from accessing the crime scene — a move that further inflamed tensions between state and federal authorities.

Pretti’s death has reverberated far beyond Minneapolis. Protesters gathered within hours of the shooting, prompting the deployment of tear gas, flash bangs, and the mobilisation of the National Guard. Political leaders traded accusations, with President Donald Trump claiming local officials were inciting “insurrection” and Minnesota leaders accusing federal agents of sowing chaos.

For many in Minneapolis, the fact that Pretti was a healthcare worker — a professional devoted to saving lives — has sharpened the moral and legal questions surrounding the incident.

As investigations unfold, his killing has become emblematic of a broader national reckoning: not only over immigration enforcement, but over the boundaries of federal power, the credibility of official narratives, and the human cost of policies executed at speed and under force.

What remains undisputed is that Alex Pretti was not a faceless suspect. He was a nurse, a researcher, a son, and a man whose life and death now sit at the centre of one of the most volatile confrontations between federal authority and civilian oversight in recent US history.

The fatal shooting of an “armed man” by federal agents in Minneapolis on Saturday marked the third such incident involving immigration authorities in the city in recent weeks. Video footage circulating online shows multiple agents wrestling the man to the ground before gunfire erupts. Officials have yet to identify the victim or publicly account for the sequence of events that led to the use of lethal force.

The man killed by federal agents in Minneapolis on Saturday was identified as Alex Pretti, a 37-year-old intensive care nurse whose death has intensified scrutiny of the Trump administration’s immigration enforcement surge and the use of lethal force on American streets.

For the Trump administration, the incident has been framed as a necessary act of enforcement in a volatile environment. For critics, it has become the latest manifestation of a federal immigration campaign increasingly defined by opacity, escalating force, and disputed claims about who is being targeted.

What is emerging across court filings, public records, and international human rights warnings is a more complex — and legally unsettled — picture, one that stretches beyond immigration policy into fundamental questions about due process, accountability, and the limits of federal power.

Trump launches new ICE immigration crackdown in Maine

Federal officials say more than 100 people were detained in Maine during what Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) branded “Operation Catch of the Day,” a name that itself drew criticism for trivialising the gravity of detention and removal. ICE described the operation as a focused effort to remove “the worst of the worst,” citing alleged child abusers, hostage takers, and violent criminals.

Yet court records examined by the Associated Press complicate that account. While some detainees had documented felony convictions, others had no criminal convictions at all, faced charges that were later dismissed, or were swept up while immigration proceedings remained unresolved.

Among the cases highlighted by ICE was that of Dominic Ali, a Sudanese national with serious assault convictions. His criminal history is not in dispute. But other individuals publicly cited by ICE as emblematic of the operation included people whose only recorded encounters with the justice system involved traffic-related offences or administrative violations.

Elmara Correia, an Angolan national singled out by ICE, was described by the agency as having been arrested for child endangerment. Maine court records instead show a dismissed charge related to learner’s permit regulations. Her attorney has said Correia entered the United States legally on a student visa and had never been subject to expedited removal.

“Was she found not guilty, or are we just going to be satisfied that she was arrested?” Portland’s mayor, Mark Dion, asked publicly — a question that goes to the heart of the legal distinction between allegation and conviction, and one that immigration enforcement does not erase.

Immigration attorneys say the Maine operation mirrors enforcement surges unfolding across the country. Boston-based attorney Caitlyn Burgess filed habeas petitions on behalf of detainees transferred from Maine to Massachusetts, noting that the most serious allegation faced by any of her clients was driving without a licence.

“Habeas petitions are often the only tool available to stop rapid transfers that sever access to counsel and disrupt pending immigration proceedings,” she said.

Attorney Samantha McHugh, representing eight Maine detainees, reported that none of her clients had criminal records. According to her filings, several were detained at workplaces or during lunch breaks by agents arriving in unmarked vehicles.

Federal court records confirm that immigration cases involving old convictions can remain unresolved for decades. In some instances, removal orders have been vacated and returned to immigration courts for reconsideration, creating legal limbo that resurfaces years later under new enforcement priorities.

Renée Good’s death at the hands of a federal immigration agent in Minneapolis on January 7, 2026, has become a focal point in national discussions about due process, lethal force standards, and civilian oversight of federal enforcement operations.

It is against this backdrop that Minneapolis has emerged as the epicentre of escalating confrontations between federal agents and civilians.

The man killed by federal agents in Minneapolis on January 24 has since been identified as Alex Pretti, a 37-year-old Minneapolis resident and intensive care nurse, according to his family and law enforcement officials. Authorities say Pretti was armed at the time of the encounter, a claim disputed by state officials who say video footage raises serious questions about the federal account of events.

On January 7, U.S. citizen Renée Good was fatally shot by an ICE officer during an enforcement operation. On January 24, another man was killed following a physical struggle with agents near a neighbourhood business. The Department of Homeland Security said the man was armed and that a firearm was recovered from a nearby vehicle.

Minnesota’s governor, Tim Walz, described the shooting as “sickening” and urged President Donald Trump to end the operation, calling for the removal of what he characterised as “violent, untrained officers.” Senator Amy Klobuchar echoed that demand, accusing congressional Republicans of silence amid repeated lethal incidents.

The frequency of such encounters has intensified scrutiny not only of individual shootings, but of the broader enforcement framework in which they occur.

As federal enforcement has expanded, so too have civilian efforts to monitor it.

Following Good’s death, advocacy groups in Minnesota reported a sharp increase in volunteers registering as ICE observers — civilians trained to document arrests, record agents in public spaces, and alert communities to active enforcement. According to CNN, these observers include parents, teachers, clergy members, and retirees.

First Amendment specialists argue that filming agents in public is a protected act, not a criminal one. Physical obstruction is a crime; documentation is a right. Yet, federal rhetoric increasingly treats these civilian observers as targets rather than witnesses.

Federal officials, however, have increasingly portrayed such monitoring as dangerous or unlawful. The Trump administration has described some ICE observers as “domestic terrorists,” while the Department of Homeland Security has launched investigations into activists who publish information about agents online.

Law professors caution that while physically interfering with officers is illegal, observation and documentation are not — a distinction that has become increasingly blurred in public rhetoric and enforcement practice.

The math of federal enforcement is shifting. Since January 2025, immigration agents have been involved in at least 27 shootings across the United States. Six of these encounters proved fatal. This surge represents a departure from historical norms of civil immigration enforcement.

Most local police departments operate under strict restrictive policies regarding discharging firearms into moving vehicles. Federal agencies, however, maintain a more permissive "objective reasonableness" standard. This creates a legal gray zone where federal agents use lethal tactics that would trigger immediate local internal affairs investigations.

Federal records reveal a startling pattern of escalation. Of the 27 incidents recorded since the start of 2025, the following trends emerge:

Vehicle Discharges: 14 incidents involved agents firing into or at moving vehicles, a high-risk maneuver.

Bystander Risk: Three of these shootings occurred in crowded commercial zones during daylight hours.

Identity Error: In two cases, including the Renée Good shooting, the targets were confirmed U.S. citizens.

The friction is no longer just about who belongs in the country. It is about how the state behaves when it enters a neighborhood. We are witnessing the "criminalization of civil status" in real-time.

Federal officials argue that increased resistance justifies increased force. They point to a rise in verbal and physical interference from "ICE observers" and civilian monitors. Yet, the data suggests that force is often used as a first resort to maintain operational speed.

When speed replaces scrutiny, the constitutional "reasonableness" of an officer's actions becomes a moving target. These 27 shootings are not outliers; they are the new baseline for a system under extreme political pressure. Accountability now lags dangerously behind the trigger.

Federal agents at the scene of a Minneapolis shooting involving immigration authorities, amid growing public concern over lethal force used during federal enforcement operations.

Taken together, the Maine detentions, the Minneapolis shootings, and the criminalisation of civilian oversight suggest a federal immigration strategy operating at the outer edge of legal authority. In this environment, speed overtakes scrutiny, narrative outruns evidence, and accountability lags behind force.

As habeas petitions multiply, protests intensify, and international scrutiny grows, the legal question confronting the administration is no longer whether immigration enforcement has become aggressive.

It is whether the legal framework governing it — from due process to use-of-force standards — can withstand the pressure now being placed upon it.

At the heart of the enforcement surge lies a tension that cuts across immigration law, constitutional protections, and the lawful use of force.

Immigration enforcement is civil, not criminal. That distinction is foundational. An arrest by ICE does not require a criminal conviction, but it does not nullify due-process guarantees. Court records from Maine show that several detainees publicly branded as dangerous offenders had unresolved cases, dismissed charges, or no criminal record at all — yet were rapidly detained and transferred, often forcing attorneys to seek emergency judicial intervention simply to preserve access to counsel.

Use-of-force standards draw an even firmer boundary. Under international law, lethal force is lawful only as a last resort against an imminent threat to life. That principle applies regardless of immigration status. Recent shootings involving federal agents — including the killing of a US citizen — have raised acute questions about whether those standards are being met.

Oversight itself has become contested terrain. Legal scholars note that recording law enforcement and observing enforcement activity are constitutionally protected acts. Physical obstruction is illegal; documentation is not. Yet federal rhetoric has increasingly collapsed that distinction.

What is being tested, in real time, are the outer limits of federal authority — and the resilience of legal safeguards designed to restrain the state when enforcement accelerates beyond accountability.

The violence on Manchester’s Curry Mile this week did not begin with a dispute about Britain.

It began with Syria.

Fights between groups of people of Kurdish and Syrian heritage, smashed shop windows, damaged cars and a stabbing that sent a 23-year-old man to hospital were all sparked by events thousands of miles away — clashes between Syrian government forces and Kurdish-led groups in the Middle East. Yet the confrontation played out not in Damascus or Aleppo, but on Wilmslow Road, one of Manchester’s most recognisable commercial streets.

Police described the protests as “largely peaceful.” Local businesses boarded up.

The question raised by the disorder is uncomfortable but unavoidable: what happens when conflicts from abroad are imported wholesale into British public space — and is the UK prepared to manage the consequences?

Britain has long defended the right to protest, including protests rooted in international politics. Demonstrations over Gaza, Ukraine and Iran have all unfolded peacefully across the UK in recent years.

What unfolded in Manchester crossed a different line.

This was not simply an expression of solidarity or dissent. It involved confrontations between distinct diaspora groups, property damage, dispersal orders, mass police deployment, and a serious stabbing during what had been billed as a peaceful gathering at Exchange Quay.

Local business owners made clear they were not participants in any political dispute. One jeweller described “swarms of people” attempting to smash windows, forcing staff to barricade themselves inside. Another said there had been no prior community tension — until geopolitics arrived uninvited.

This distinction matters. Peaceful protest challenges power. Imported conflict destabilises neighbourhoods.

As disorder spread, the political response followed a now-predictable pattern.

Senior figures condemned the violence. Some exaggerated it. Former Conservative minister Nadhim Zahawi circulated claims of multiple stabbings that later proved false, conflating events in Manchester with a separate incident in Antwerp. Others framed the unrest as proof that Britain has “lost control of its streets,” or that migration itself is the root cause.

In Parliament, MPs clashed over asylum hotels, criminality, deportations, tagging, and deterrence. The language escalated quickly: “national emergency,” “border security crisis,” “violent disorder,” “mindless thuggery.”

Yet amid the noise, one crucial distinction was repeatedly blurred: the difference between perception and evidence.

Public debate often assumes that disorder involving migrants reflects a broader pattern of criminality. The available data does not support that assumption.

According to analysis from the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, foreign nationals account for roughly 12–13% of the prison population and criminal convictions in England and Wales — broadly in line with their estimated share of the adult population. When age and sex are taken into account, non-citizens are slightly under-represented in prison compared with British citizens.

That does not mean crime is evenly distributed. Non-citizens are over-represented in some offence categories, such as drug and fraud offences, and under-represented in others, including violent crime and robbery. Rates also vary significantly by nationality, though precise comparisons are difficult due to gaps in population data and the exclusion of people in communal accommodation, such as asylum hotels, from surveys.

Crucially, the Ministry of Justice does not record crime by immigration status. There is no comprehensive dataset showing whether asylum seekers are more or less likely to offend than the wider population.

What the data does show is this: headline-driven narratives routinely outpace the evidence.

If the Manchester clashes were not driven by a general rise in migrant criminality, what were they driven by?

The answer appears to lie less in crime statistics and more in identity fragmentation.

Kurdish and Syrian communities in the UK are shaped by recent trauma, displacement and unresolved conflict. Many arrived during or after Syria’s long civil war. Political loyalties, ethnic tensions and historical grievances did not dissolve at the border.

What Britain lacks is a clear framework for managing how those unresolved conflicts play out domestically.

Integration policy has focused heavily on employment, housing and legal status. Far less attention has been paid to civic cohesion when transnational identities collide — especially in moments of heightened geopolitical tension.

Manchester’s unrest suggests that the assumption “diversity equals harmony” is no longer sufficient on its own.

Greater Manchester Police responded with Section 34 dispersal orders, Section 60 stop-and-search powers and expanded patrols. Arrests were made. Calm was restored.

But policing can only manage symptoms.

The deeper issue is structural: Britain has become a host to multiple global conflicts without a strategy for insulating local communities from their fallout. Social media accelerates mobilisation. Rumours spread faster than corrections. Diaspora politics becomes street politics almost overnight.

As MPs across parties acknowledged during recent Commons exchanges, misinformation — particularly online — now plays a central role in turning isolated incidents into flashpoints.

There is a danger in misreading Manchester.

Downplaying the disorder risks normalising street violence as an inevitable feature of multicultural society. Overstating it risks fuelling moral panic, racialised narratives and collective blame.

The greater risk lies elsewhere: allowing foreign conflicts to repeatedly erupt on British streets without a serious conversation about integration, identity and civic responsibility.

Integration is not just about who lives here. It is about which conflicts are allowed to be fought — and which are not.

The Manchester clashes were not the largest protest Britain has seen, nor the most violent. But they may prove among the most revealing.

They exposed a gap between Britain’s self-image as a tolerant, plural society and its capacity to manage imported geopolitical tensions in real time. They showed how quickly legitimate protest can slide into communal confrontation. And they revealed how fragile public trust becomes when perception, politics and evidence pull in different directions.

The question now is not whether Britain should remain open or closed. It is whether integration can keep pace with global instability — or whether Britain will increasingly find itself hosting other people’s wars at home.

When disorder broke out in Manchester, Greater Manchester Police relied on two rarely explained but powerful legal tools: Section 34 dispersal orders and Section 60 stop-and-search powers.

Section 34 of the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act allows police to order individuals to leave a designated area for up to 48 hours if their presence is believed to contribute to harassment, alarm or distress. Failure to comply is a criminal offence. The power is preventative, not punitive — officers do not need to prove wrongdoing, only reasonable belief.

Section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act goes further. It temporarily removes the requirement for reasonable suspicion, allowing officers to stop and search individuals within a defined area if serious violence is anticipated. The threshold for authorisation is high, but once in place, civil liberties protections are significantly reduced.

Both powers are lawful, time-limited, and subject to review. But they are also blunt instruments. Civil liberties groups have long warned that frequent or prolonged use risks undermining public trust, particularly in diverse communities.

Manchester illustrates the legal dilemma clearly: the state has the authority to suppress disorder swiftly — but far less ability to prevent the conditions that trigger it.

The threat issued this Saturday was blunt and unmistakable. President Donald Trump warned Prime Minister Mark Carney that Canada could face a 100% tariff on all imports if it moves forward with a trade deal with China. On social media, Trump accused Canada of becoming a potential “drop-off port” for Chinese goods entering the United States.

It was not framed as negotiation. It was framed as punishment.

This is no ordinary dispute over dairy quotas or auto parts. The threat marks a deeper shift in how the United States now wields economic power. Tariffs are no longer trade tools — they are instruments of coercion. Alliances, once treated as durable partnerships, are now transactional assets, vulnerable to sudden liquidation.

When Trump warned that China would “eat Canada alive,” he wasn’t merely attacking Beijing. He was signaling that sovereignty itself has become conditional.

The pattern did not emerge overnight. Since returning to office, Trump has embraced volatility as leverage.

On January 20, 2025, he vowed to “tariff and tax foreign countries to enrich our citizens.” Within weeks, his administration declared a national emergency to justify 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico, bypassing Congress.

What followed was a familiar cycle: threat, partial reprieve, then escalation.

In March 2025, U.S. automakers were granted a one-month exemption — only for the tariffs to land shortly afterward. In January, Colombia was pressured with 25% tariffs until it accepted migrant deportation flights. Each episode reinforced the same message to foreign capitals: relief is temporary, and compliance is expected.

This rhythm of uncertainty forces governments into constant defensive negotiation, never knowing when the next economic strike will land.

Canada’s treatment marks a sharp break from precedent. Traditionally shielded by geography and treaty, Ottawa now finds itself spoken to like a sanctioned state.

By early 2025, aluminum tariffs had already been raised to 25%. By March, Justin Trudeau’s government retaliated with $100 billion in counter-tariffs. The political landscape shifted again with Mark Carney’s rise — but the tone from Washington hardened.

Trump’s rhetoric has grown openly predatory. After a tense Davos exchange, Carney’s invitation to Trump’s proposed “Board of Peace” was withdrawn. The message was unmistakable: follow the U.S. lead or face economic isolation.

For Canada, the threat is not theoretical. A 100% tariff would land immediately on supply chains, jobs, and consumer prices — with little room to maneuver.

The legal architecture behind this strategy allows the administration to move fast and unilaterally.

Two tools dominate:

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, which frames imports like timber, steel, and copper as national security threats

The International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), which allows sweeping economic penalties under declared emergencies

In January 2026, the White House quietly extended these emergency declarations for another year. The effect is simple: tariffs can be deployed at will, with minimal legislative oversight. The European Union has already initiated WTO action, calling the measures abusive and destabilizing.

Canada faces economic pressure. Venezuela has faced something more direct.

Following an overnight raid on January 3, 2026, the U.S. military detained President Nicolás Maduro. Days later, Trump announced that 50 million barrels of Venezuelan oil seized from tankers would be processed by U.S. refineries.

“Let’s put it this way,” Trump said. “They don’t have any oil. We take the oil.”

The operation reportedly involved a classified acoustic weapon — dubbed the “discombobulator” — used to incapacitate guards. White House officials described it as a “very intense sound wave.” The message was unmistakable: economic pressure and military force now operate on the same spectrum.

The administration’s $100 billion plan to “rebuild” Venezuela’s oil industry has been described by critics as less reconstruction than acquisition.

Trump’s “reciprocal tariff” policy, introduced in April 2025, upended decades of trade norms. By matching foreign tax rates, the U.S. imposed a 34% tariff on China, prompting Beijing to retaliate with 125% duties on American farm products.

A short-lived truce collapsed within months.

Even close allies have felt the squeeze. The United Kingdom secured a limited vehicle quota at a reduced tariff only after agreeing to import U.S. bioethanol. The deal underscored a new reality: access is conditional, and concessions are mandatory.

Britain offers a preview of what compliance looks like. A House of Commons briefing published in December acknowledged that the UK accepted a non-binding “Economic Prosperity Deal” under U.S. tariff pressure — agreeing to quotas, regulatory concessions, and large imports of U.S. bioethanol — yet still remains subject to a 10% baseline tariff on most goods.

Parliamentary committees warned the arrangement creates uncertainty for businesses and risks eroding the UK’s competitive position, underscoring a broader reality: even allies who concede do not escape Trump’s tariff regime — they merely soften its edge.

Trump has portrayed tariffs as a revenue bonanza. Economists see a different picture.

Auto-parts tariffs have disrupted supply chains at Ford and GM. Higher steel and timber prices are filtering directly to consumers. The removal of the $800 de minimis threshold in August 2025 has hit small businesses with new taxes and customs delays.

Retaliation has followed. European tariffs now target American whiskey and motorcycles, squeezing exporters already navigating rising costs.

For many households, “America First” has begun to look like consumer last.

Economists warn the cost of Trump’s tariff strategy will land fastest at home. According to analysis by the Tax Foundation, the current and threatened tariffs amount to an average tax increase of roughly $1,000 per U.S. household in 2025, rising to about $1,300 in 2026.

Even after accounting for reduced imports and behavioral shifts, the effective tariff rate would climb to its highest level since 1946, while eliminating the equivalent of nearly 450,000 full-time jobs. The projected revenue gains, analysts note, would be partially offset by slower growth, higher prices, and retaliatory tariffs abroad.

The economic stakes are substantial. Analysts at JPMorgan estimate the effective U.S. tariff rate is now climbing toward 18–20%, up from just 2.3% before Trump returned to office — a shift they describe as the largest tax increase since 1968. The bank warns the tariffs could lift consumer prices by as much as 1.5%, push real disposable income into negative territory, and materially raise the risk of recession, both in the U.S. and among close trading partners such as Canada.

The threat of a 100% tariff on Canada is not an outlier. It is the clearest expression yet of a broader shift.

Trade agreements like the USMCA still exist on paper, but in practice they have been eclipsed by bilateral pressure and brinkmanship. Whether the target is Ottawa, Caracas, or Copenhagen, the logic is the same: compliance brings relief; resistance brings punishment.

As Mark Carney warned in Davos, this is not a transition — it is a rupture. In 2026, tariffs are no longer about trade balances. They have become the primary weapon of a new, coercive global order.

US immigration authorities are facing mounting scrutiny after asserting that federal agents can forcibly enter private homes without a judge’s approval – a claim constitutional scholars, immigration lawyers and a federal judge have described as a clear violation of the Fourth Amendment.

An internal Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) memo issued in May instructs agents that they may use force to enter residences armed only with an administrative warrant, according to a whistleblower disclosure reviewed by USA Today and first reported by the Associated Press. Unlike judicial warrants, administrative warrants are signed internally by ICE officials and are not reviewed or approved by a judge.

The directive represents a sharp break from longstanding legal precedent and established policy across the Department of Homeland Security, which has historically required a warrant issued by an independent judge before agents could enter a home to make an arrest.

The memo emerged amid an aggressive expansion of the Trump administration’s deportation campaign, marked by large-scale enforcement operations and a rapid hiring push that has more than doubled ICE’s workforce. How often the policy has been used remains unclear.

What is clear, however, is the growing public fallout.

On 18 January, federal agents with guns drawn forced their way into a home in St Paul, Minnesota, detaining ChongLy Thao, a naturalized US citizen. Family members and local officials said agents never produced a judicial warrant. Images of Thao being led outside shirtless in freezing weather quickly spread online, prompting outrage and calls for an independent investigation. ICE later said agents had been searching for a different person.

Federal officials have sought to downplay constitutional concerns. Marcos Charles, a senior ICE official, said in January that agents do not “break into” homes, insisting entry is made either during “hot pursuit” or with an administrative arrest warrant – documents he claimed courts have deemed sufficient for immigration enforcement.

During a visit to Minneapolis, Vice-president JD Vance echoed that position, saying agents would not enter homes “without some kind of warrant”, while acknowledging that could include administrative paperwork rather than a judge’s order. He conceded the policy would likely face legal challenges.

Civil liberties experts say the distinction is fundamental – and dangerous.

Administrative warrants, including Form I-205, authorize the arrest of individuals with final orders of removal but are not reviewed by the judiciary. They can be signed by ICE officials, sometimes by the very agents carrying out the arrest. Judicial warrants, by contrast, require an independent judge to assess evidence and determine whether forced entry into a home is justified.

“This goes to the heart of the Fourth Amendment,” said Ric Simmons, a constitutional law professor at Ohio State University. “The entire point is to require law enforcement to justify invading someone’s home to a neutral decision-maker outside the executive branch.”

Legal scholars warn that conflating administrative paperwork with judicial warrants strips away one of the most basic safeguards against state overreach.

In 2024, a federal judge in California reached the same conclusion, ruling that ICE agents may not enter homes without a judicial warrant and declaring that such actions violate the Constitution. The new memo explicitly carves out an exception for that jurisdiction.

The Supreme Court has recognized only narrow circumstances in which officers may enter a home without a warrant – typically emergencies involving imminent danger or the risk of evidence being destroyed. Immigration enforcement, experts note, is a civil process, not an emergency.

“There’s no emergency here,” Simmons said. “They’re not claiming one. It’s a civil law violation, and the courts have been very clear about that.”

The memo also appears to contradict ICE’s own training materials. A 2021 ICE guide states explicitly that a warrant of removal “does NOT alone authorize a Fourth Amendment search of any kind”.

Despite this, the May memo – signed by the acting ICE director – claims government lawyers have recently determined that administrative warrants are sufficient under the Constitution and immigration law. No detailed legal justification has been publicly released.

Whistleblowers allege the policy was quietly rolled out, shared verbally with supervisors and new recruits rather than formally circulated. According to a disclosure submitted to members of Congress, agents were instructed to read the memo briefly and return it, limiting documentation.

The whistleblowers warn that many newly hired agents lack prior law enforcement experience and are being encouraged to rely on administrative warrants to enter homes without consent – including homes belonging to US citizens.

“That raises the risk of widespread, unlawful intrusions into private residences,” the disclosure states.

For legal experts, the secrecy surrounding the policy is itself revealing.

“This is not how an agency behaves when it’s confident its actions will withstand judicial scrutiny,” said Lindsay Nash, a law professor at Yeshiva University’s Cardozo School of Law. “ICE has long acknowledged that administrative warrants do not authorize forced home entry. Trying to reverse that quietly will be extraordinarily difficult to defend in court.”

As legal challenges loom, the directive has intensified fears among immigrant communities and civil rights advocates that constitutional protections long considered settled are being deliberately tested – or ignored – in the name of enforcement.

The central legal question raised by ICE’s directive is not abstract. It is immediate, personal and constitutional: can federal immigration agents legally force their way into your home without a judge’s warrant?

Under the Fourth Amendment, law enforcement officers may not enter a private home without either voluntary consent or a warrant issued by an independent judge, except in rare emergency circumstances. Immigration enforcement, which is civil rather than criminal, does not create a blanket exception.

Administrative warrants – the documents ICE says it relies on – do not meet that standard.

They are signed internally by ICE officials, not reviewed by a judge, and do not authorize forced entry into a home. Courts have repeatedly drawn that line, and ICE itself acknowledged it in its own training materials until recently.

ICE is leaning on a legal theory that immigration enforcement falls under “civil” authority and therefore does not require the same constitutional safeguards as criminal policing. Some government lawyers argue this places immigration arrests closer to regulatory actions than criminal searches.

But constitutional scholars say that argument collapses at the front door.

The Supreme Court has consistently ruled that the home is afforded the highest level of Fourth Amendment protection, regardless of whether the government action is civil or criminal. The “special needs” and emergency exceptions ICE may try to invoke are narrow and do not apply to routine immigration arrests.

No. Policies do not override the Constitution.

ICE can issue internal directives, but they do not become lawful simply because the agency says so. If agents enter homes without judicial warrants, those actions are vulnerable to legal challenge, suppression of evidence, civil liability and court injunctions.

In fact, a federal judge in California already barred ICE from doing exactly this in 2024, ruling that warrantless home entry violates the Fourth Amendment. That ruling remains binding in that jurisdiction and signals how other courts are likely to respond.

Legal experts are clear on this point:

You are not required to open the door unless agents present a judicial warrant signed by a judge

An administrative ICE warrant does not authorize forced entry

You have the right to ask officers to slide the warrant under the door or hold it up to a window

Silence or refusal to open the door is not consent

If agents enter anyway without a judicial warrant or exigent circumstances, that entry may later be ruled unlawful.

Because ICE’s position conflicts with:

Supreme Court precedent

Existing federal court rulings

DHS’s own historical policy

ICE’s own training manuals

That combination makes the directive legally fragile. Courts are especially skeptical when agencies quietly reverse long-standing constitutional interpretations without public explanation or legislative change.

Legal experts expect lawsuits challenging unlawful entries, requests for nationwide injunctions, and potential damages claims — particularly in cases involving US citizens or lawful residents.

ICE can say it has this authority.

That does not mean the courts will agree.

And if history is any guide, they likely won’t.

There are moments when celebrity feminism, usually delivered in neat slogans and Instagram-ready clarity, becomes something messier. This week, that mess arrived via a set of private messages, newly unsealed court documents, and a series of sharply worded texts involving Jameela Jamil, Blake Lively, and the ongoing legal battle surrounding Justin Baldoni.

The messages, exchanged in August 2024 between Jamil and Baldoni’s publicist Jennifer Abel, revealed the actor and activist describing Lively as a “suicide bomber” and a “villain” amid criticism of her promotional approach to It Ends With Us, a film centred on domestic violence. The language, once private, is now public — and Jamil has chosen not to retreat from it.

Instead, she has reframed the conversation.

In a video posted to Instagram Stories on Thursday, Jamil defended both her comments and her understanding of feminism itself. Feminism, she argued, is not about universal likability or compulsory sisterhood. It is, she said, “fighting for the political, social and economic equity for women — just gender equity.”

That definition, she stressed, allows room for conflict.

“It doesn’t mean you have to like every single woman,” Jamil said. “You can criticise them. You can beef with them. You can do whatever you want — as long as you are also fighting for their human right to the same things men have.”

The tone was deliberately provocative. Feminism, she added, is “a moral and political stance”, not “a sleepover where we braid each other’s pubes”.

Jamil did not mention Lively by name, but the timing was unmistakable. Days earlier, the Daily Mail had reported on the court documents, which surfaced as part of Baldoni’s sprawling legal dispute with Lively — a case that has become as much about reputation and power as about what allegedly occurred on set.

The original exchange centred on backlash Lively faced during the film’s press run, when critics accused her of promoting her haircare brand and fashion choices while sidestepping the film’s themes of domestic abuse. In one message, Abel vented her frustration in explicit terms. Jamil replied tersely: “She’s a suicide bomber at this point.” Later, she described Lively’s conduct as a “bizarre villain act”.

The fallout has been swift. A source close to the situation described the comments as “disappointing”, particularly given that Lively has accused Baldoni of sexual harassment — allegations he has repeatedly denied.

The legal battle itself has become labyrinthine. By December 2024, Lively had filed a formal complaint and later a lawsuit against Baldoni. He responded with a $400m countersuit, accusing Lively and her husband, Ryan Reynolds, of defamation, and separately sued The New York Times for libel over its reporting on the case. A judge later dismissed both countersuits, though Lively’s claims remain unresolved.

Against this backdrop, Jamil’s defence reads less like damage control and more like a philosophical line in the sand. Her argument is not that her language was gentle — it plainly wasn’t — but that feminism does not require silence, alignment or emotional unanimity.

It is a position that resonates with some and alarms others. Critics argue that the rhetoric undermines the principle of listening to women who speak out. Supporters counter that political solidarity does not preclude personal critique — even sharp, ill-judged critique — especially within elite celebrity spaces where power is unevenly distributed and reputations are carefully engineered.

What is clear is that this is no longer just a story about leaked texts. It is about how feminism operates when filtered through fame, legal strategy and public spectacle — and how quickly ideals fracture when they collide with real people, real money and real consequences.

In the age of unsealed documents and screenshot justice, even private language now carries a public afterlife. And once again, celebrity culture is left to debate not only who was right or wrong — but who gets to define what solidarity looks like when the stakes are this high.

Blake Lively, Justin Baldoni Legal Battle: Taylor Swift Texts

One question raised by the release of private messages is whether language alone can create legal risk. In most circumstances, it cannot — and the distinction is central to how US civil law operates.

Courts draw a firm line between alleged conduct and commentary about that conduct. Civil claims such as sexual harassment or hostile work environment hinge on behaviour, patterns of treatment and workplace conditions, not on whether third parties used offensive or hyperbolic language when reacting to a dispute. Even crude or inflammatory remarks, when expressed privately, rarely meet the legal threshold for liability.

That threshold is higher still where statements are framed as opinion rather than fact. Insults, rhetorical exaggeration and moral judgements — however distasteful — are generally protected unless they are presented as provably false assertions about a person’s actions and published in a way that causes demonstrable harm. Calling someone a “villain”, for example, is legally distinct from alleging specific wrongdoing.

Where private communications can become legally relevant is in context rather than culpability. In complex civil cases, courts may examine messaging to assess motive, alignment or escalation, particularly where reputational damage, retaliation or coordinated media strategy is alleged. Such material can shape the narrative of a case without expanding its legal scope.

Crucially, being named in unsealed documents does not make someone a party to a lawsuit, nor does it imply shared responsibility. Liability remains confined to the individuals and claims formally before the court, and courts are typically cautious about widening that boundary.

The result is a dynamic familiar to high-profile disputes: material that carries cultural and reputational impact can coexist with legal questions that remain narrowly defined. What resonates publicly does not necessarily alter what must ultimately be proven.

For readers following the case, the legal reality is straightforward. Language may influence perception, settlement pressure or public debate — but it is evidence of conduct, not commentary, that determines how the law will finally weigh the claims.

A former Conservative councillor has pleaded guilty to drugging and raping his former wife repeatedly over a period spanning more than a decade, admitting dozens of serious sexual offences.

Philip Young, 49, entered guilty pleas at Winchester Crown Court to 48 offences committed against Joanne Young between 2010 and 2024. The offences include 11 counts of rape, multiple sexual assaults, administering substances with intent to stupefy or overpower, voyeurism, and the publication of non-consensual intimate images.

Ms Young, who has waived her right to lifelong anonymity, was present in court and sat opposite her former husband during the hearing. The couple divorced following Young’s arrest in 2024.

Prosecutors said some of the offences involved other men, several of whom appeared in court alongside Young and deny allegations of sexual offences. One defendant has yet to enter pleas. Those co-accused were released ahead of a trial scheduled to begin in October and expected to last up to six weeks.

One voyeurism charge related to at least 200 occasions, while Young also admitted publishing intimate images and videos of his former wife on hundreds of occasions without her consent.

Young, who served as a Swindon borough councillor between 2007 and 2010, has been remanded in custody.

Following the hearing, the Crown Prosecution Service said Young had admitted “dozens of serious sexual offences” and paid tribute to Ms Young’s decision to come forward. Wiltshire Police also praised her “incredible bravery”, describing the guilty pleas as a significant moment in the case.

Sentencing will take place at a later date.

Amanda Knox’s return to Italy has revived public debate about exoneration, but the law treats “being cleared” far more narrowly than many assume. While her conviction was overturned and later annulled, exoneration does not automatically erase legal, reputational, or procedural consequences.

When Amanda Knox returned to Italy in 2022 and came face to face with the prosecutor from her murder case, the moment was widely presented as an act of personal reckoning — a gesture of closure, or even reconciliation.

In legal terms, however, her position had long since been resolved. The significance of the return lay less in what it reopened than in what it quietly underscored about how justice systems close cases without closing consequences.

Knox’s conviction for the 2007 murder of Meredith Kercher was overturned, and in 2015 Italy’s highest court annulled the judgment against her entirely. That ruling extinguished her criminal liability. It did not, and could not, undo the years of incarceration, the procedural record left behind, or the public narratives that hardened while the legal process unfolded.

That distinction — between legal finality and lived aftermath — has resurfaced repeatedly in Knox’s public life, including in her recent exchanges with Matt Damon, who suggested that for some people, a fixed prison sentence might be preferable to the indefinite punishment of public ostracism.

Knox’s response was pointed but grounded in experience: imprisonment is neither discreet nor finite in its effects, and exoneration does not reset the social or reputational clock.

In that sense, the renewed attention around her case illustrates a core legal reality that extends well beyond celebrity: exoneration ends criminal responsibility, but it does not erase prior proceedings, restore reputation by operation of law, or neutralise the collateral consequences that can persist long after a court has spoken. It is a gap the justice system acknowledges, but does not — and often cannot — close.

Amanda Knox was convicted in Italy in 2008 and spent nearly four years in prison before her conviction was overturned on appeal in 2011. In 2015, Italy’s Court of Cassation — the country’s highest criminal court — annulled the judgment against her entirely, bringing the case to a definitive legal close. Her former boyfriend, Raffaele Sollecito, was cleared on the same basis.

A third defendant, Rudy Guede, was convicted separately after traces of his DNA were found at the crime scene. He served a prison sentence following that conviction.

More than a decade after her release, Knox returned to Italy in 2022 to speak at an Innocence Project conference and later met with the prosecutor associated with her original prosecution. That encounter forms part of a documentary released years after her exoneration had already become final under Italian law.

No new charges were filed, no appeals reopened, and no judicial proceedings were revived as a result of the visit. From a legal standpoint, the case remained exactly where it had stood since 2015: closed.

At the centre of this story is the legal meaning of exoneration — and, just as importantly, its limits.

In practical terms, exoneration occurs when a conviction is overturned and the defendant is formally cleared under the governing appellate standards. In Italy, that process can involve annulment by the Court of Cassation, typically on the basis that the evidence was insufficient or the proceedings themselves were legally flawed. The effect is final: the conviction cannot stand.

What that ruling does not do is more often misunderstood. Exoneration does not automatically erase the procedural record of a case, remove earlier judicial findings from the public domain, or confer compensation or apology as a matter of course. Nor does it prevent third parties — including the media or cultural producers — from revisiting the events, however imperfectly.

Each of those outcomes, where they occur at all, arises through separate legal routes, subject to distinct standards and discretionary judgments. Exoneration ends criminal liability. It does not, by operation of law, restore a person to the position they occupied before the case began.

Not in the way the term is commonly understood. Exoneration means that a conviction has been found legally unsustainable and cannot stand. Appellate courts typically reach that conclusion by assessing evidentiary sufficiency, procedural fairness, or legal error. They do not conduct a separate inquiry aimed at affirmatively proving innocence, nor do they apply a distinct standard for doing so.

They are not. Earlier judgments, filings, and contemporaneous reporting generally remain part of the public and procedural record. Courts do not retroactively expunge proceedings simply because a conviction is overturned, even where the ultimate outcome is a full annulment.

In most legal systems, it does not. Compensation, where available, usually requires a separate application and proof that defined statutory or judicial thresholds have been met — such as unlawful detention or a demonstrable miscarriage of justice. Exoneration alone is rarely sufficient.

Only in exceptional circumstances. Prosecutorial conduct is typically shielded by immunity doctrines, and mechanisms for judicial accountability are narrowly drawn. The fact of exoneration does not, by itself, establish misconduct or legal fault.

Yes. Even after criminal liability has been extinguished, the effects of a prosecution can persist — through reputational damage, professional scrutiny, travel or administrative complications, and renewed public attention. Legal finality does not necessarily bring social or practical closure.

Knox’s case points to a broader legal reality that is often obscured by high-profile narratives. Criminal justice systems are built to determine liability and bring proceedings to an end; they are not designed to comprehensively repair the damage caused when a prosecution goes wrong.

For most defendants, exoneration brings an end to incarceration, supervision, or formal criminal exposure. It does not, however, guarantee financial redress, reputational recovery, or a sense of closure proportionate to what was lost. Those outcomes, where they occur at all, tend to arise unevenly and through separate processes, rather than as a natural consequence of being legally cleared.

Understanding that distinction matters well beyond this case. It shapes how wrongful convictions are discussed, how expectations are set, and how the limits of legal remedies are often mistaken for moral or social resolution.

For an individual who has been exonerated, the formal conclusion of a criminal case does not necessarily mark the end of all legal avenues.

Depending on the jurisdiction, it may be possible to seek correction or limitation of criminal records, pursue compensation through statutory schemes, or bring civil claims — each subject to its own thresholds, evidentiary burdens, and, in some cases, significant immunity barriers. Others turn instead to public advocacy or legislative reform, not as a legal remedy in itself, but as a means of addressing systemic gaps left unfilled by the courts.

These pathways operate independently of one another. None arise automatically from exoneration, and none are guaranteed to deliver outcomes proportionate to the harm experienced.

Amanda Knox’s legal status has been settled for more than a decade. Yet her case continues to illustrate the narrowness of what exoneration accomplishes in strictly legal terms. Criminal liability can be brought to a decisive end, while the professional, reputational, and personal consequences of prosecution persist.

That disjunction is not peculiar to this case. It is a structural feature of modern justice systems — and a reminder that being legally cleared is not the same as being restored.

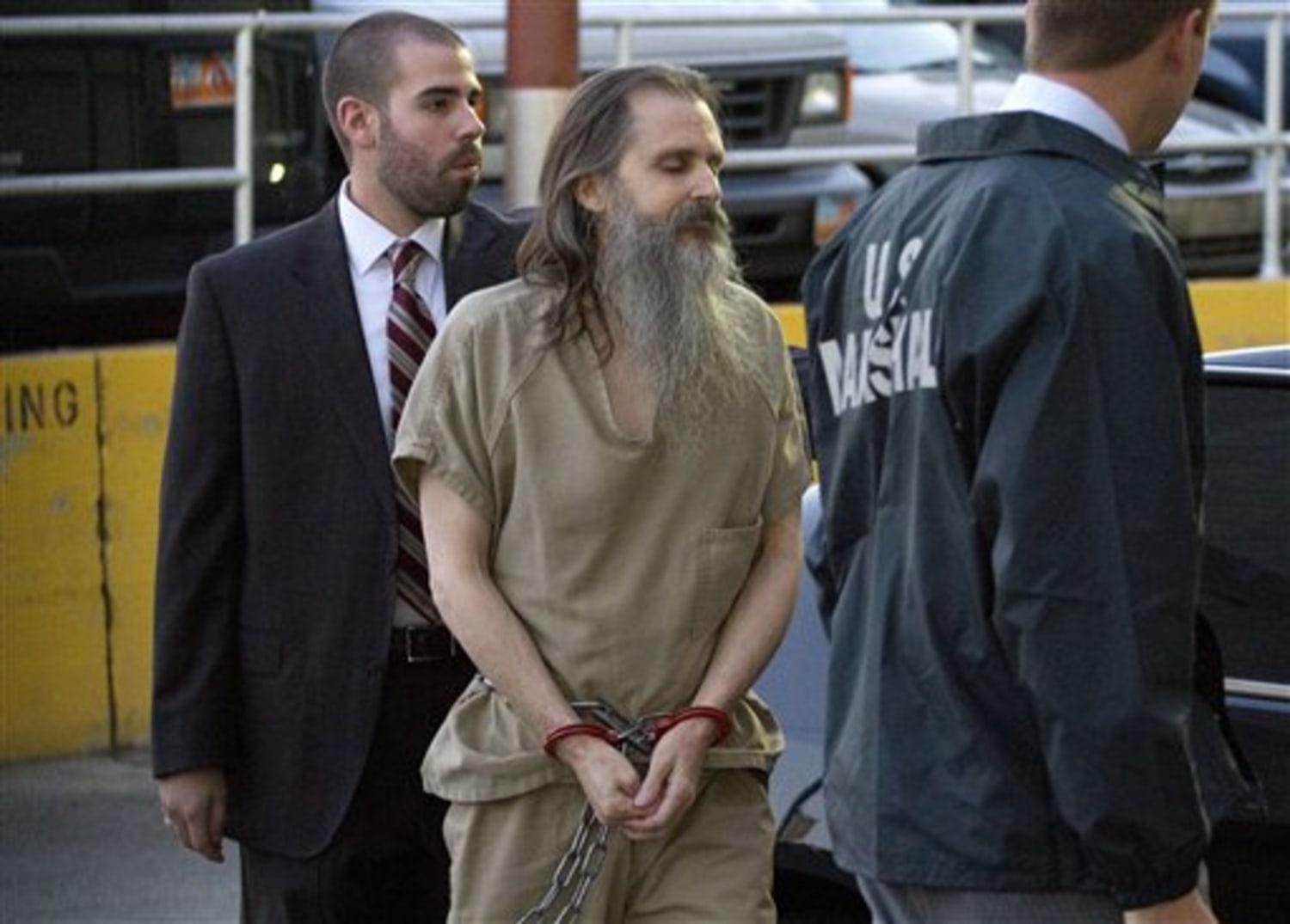

Brian David Mitchell is led by U.S. Marshals while in federal custody. Mitchell is serving a life sentence without parole for the kidnapping of Elizabeth Smart.

Brian David Mitchell was raised in a middle-class Mormon household in Salt Lake City, the third of six children. His father worked as a social worker and emphasized strict religious discipline in the home. Family members later said Mitchell was bright and capable, excelling academically and showing aptitude in music and skilled trades, including carpentry.

But even early on, those close to him noticed something was off. Teachers and relatives described him as increasingly withdrawn, prone to emotional swings, and detached from peers. As he entered adolescence, that detachment hardened into isolation, accompanied by anger and volatility, particularly in conflicts with his father over religion and authority.

At 16, Mitchell was arrested after exposing himself to a young girl. Though he avoided long-term incarceration, the incident became an early marker in a pattern of sexually inappropriate behavior that would follow him into adulthood.

Mitchell’s working life was unstable. Over the years, he cycled through jobs as a salesman, hospital orderly, and sandblaster, among others. None lasted. According to later testimony, he became increasingly consumed by fringe religious ideas, spending long periods immersed in his own interpretations of scripture and prophecy.

He married young. In 1972, Mitchell wed Karen Layne, and the couple had children before the marriage eventually collapsed. During divorce proceedings, allegations of child sexual abuse surfaced — claims that were documented but never resulted in criminal convictions. Mitchell moved on, avoiding lasting legal consequences.

In the mid-1980s, he married Wanda Barzee, a divorced mother of six. Their relationship marked a turning point. Mitchell’s religious beliefs intensified, and Barzee, by her own later account, came to see him as divinely chosen. The couple withdrew further from mainstream society, eventually selling their possessions and living transiently.

As they drifted between campsites and city streets, Mitchell’s belief system hardened. What had once appeared eccentric became rigid and absolute — a worldview in which obedience was mandatory and women and children were assigned roles within his self-declared spiritual mission.

Years later, prosecutors would argue that this isolation — paired with Mitchell’s need for control — created the conditions that made the kidnapping of Elizabeth Smart possible, echoing patterns of warning signs and missed intervention later debated in other high-profile cases, including JonBenét Ramsey and the Menendez brothers.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(971x217:973x219)/elizabeth-smart-kidnappers-brian-david-mitchell-wanda-barzee-main-060625-e8f39d9596bc4170a0fc5154fc4d4117.jpg)

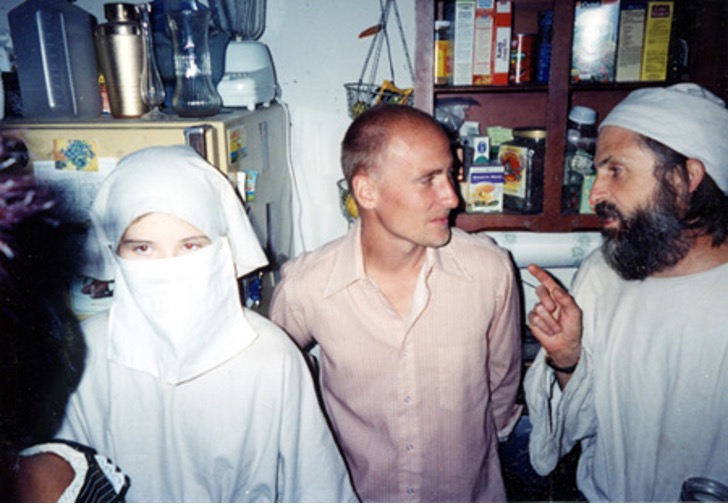

Archival images related to the Elizabeth Smart kidnapping case, showing the convicted kidnapper, Elizabeth Smart as a teenager, and his wife and accomplice during court proceedings.

In November 2001, Brian David Mitchell crossed paths with the Smart family in an unremarkable way. He was panhandling on the streets of Salt Lake City when Elizabeth Smart’s mother, Lois, stopped and spoke with him. She offered him $5 and later gave him a small roofing job at the family’s home — an act of generosity that, at the time, raised no alarms.

Months later, Mitchell returned.

In the early morning hours of June 5, 2002, he broke into the Smart home while the family slept. Armed with a knife, he entered the bedroom Elizabeth shared with her younger sister and forced the 14-year-old to leave quietly, threatening to kill her and her family if she resisted.

Elizabeth was made to walk miles into the foothills outside Salt Lake City, where Mitchell’s wife, Wanda Barzee, was waiting.

There, Elizabeth was dressed in religious clothing and subjected to a ceremony Mitchell described as a marriage. What followed was months of captivity. Elizabeth was repeatedly raped, often restrained with a cable to prevent escape, and kept under constant threat. She was deprived of food, drugged, and warned that any attempt to run would end in her death.

Barzee was present throughout the captivity. Elizabeth later said she witnessed the abuse and did nothing to intervene, believing she was obligated to obey Mitchell’s religious authority.

Despite being taken into public spaces during those nine months — including city streets and stores — Elizabeth remained hidden. Disguised, controlled, and coerced into silence, she was repeatedly seen but not recognized.

She would not be rescued until March 2003.

In the hours after Elizabeth Smart was taken from her Salt Lake City home, law enforcement launched an intensive search of the surrounding neighborhoods and foothills. Sniffer dogs were brought in and initially picked up Elizabeth’s scent, tracking it toward the edge of a wooded area near the family’s home.

The trail, however, went cold at the forest line. Investigators later said the loss of scent complicated early efforts, as Mitchell had forced Elizabeth to walk through terrain that made tracking difficult. Despite the setback, volunteers and officers continued canvassing the area, calling out Elizabeth’s name as part of organized search parties.

Elizabeth would later reveal that she could hear those searchers. While being held nearby, she listened as people called her name, aware that help was close but unable to respond without risking severe punishment. At the time, she was being held in makeshift camps, including a teepee-like shelter concealed in the foothills, where her captors moved frequently to avoid detection.

For months, the search continued without answers. The case drew national attention, but Elizabeth remained hidden — close enough to hear rescuers, yet just out of reach.

An archival image connected to the Elizabeth Smart kidnapping investigation, showing the survivor during captivity alongside her captors inside a private residence.

The investigation took a crucial turn months after Elizabeth Smart disappeared, when her younger sister, Mary Katherine Smart, told her parents she believed she recognized the kidnapper’s voice. It reminded her of a man the family had once known as “Immanuel,” who had briefly worked on their roof.

That realization led investigators to focus on Brian David Mitchell. In February 2003, police released a composite sketch, followed by photographs provided by Mitchell’s family. The images were broadcast nationally, including on America’s Most Wanted, significantly widening the search.

On March 12, 2003, two separate couples who had seen the broadcasts spotted Mitchell walking in Sandy, Utah, accompanied by two women. They contacted police, who stopped the group shortly afterward.

Elizabeth, wearing a disguise and giving officers a false name, was taken into custody along with Mitchell and his wife, Wanda Barzee. At the police station, Elizabeth eventually confirmed her identity and was reunited with her family later that day.

The legal process that followed stretched on for years, delayed by repeated mental competency evaluations. Mitchell’s attorneys argued he was not criminally responsible due to mental illness, but a federal jury ultimately rejected that defense.

In December 2010, Mitchell was convicted of interstate kidnapping with intent to commit sexual assault and sentenced to life in federal prison without the possibility of parole. Barzee pleaded guilty in a separate case and received a 15-year sentence. She was released in 2018 — a decision Elizabeth Smart later said left her “surprised and disappointed.”

The convicted kidnapper Brian David Mitchell in the Elizabeth Smart case appears in court under guard. He is currently serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole in federal prison.

Mitchell is now 72 years old and serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole. He remains in federal custody, where he is expected to spend the rest of his life.

In late 2025, Mitchell’s incarceration status changed following a reported assault while he was housed at the high-security federal prison in Terre Haute, Indiana. According to public reporting, he was attacked by another inmate, prompting prison officials to move him out of the facility.

Mitchell was subsequently transferred to Federal Correctional Institution Lewisburg in Pennsylvania, where officials confirmed he is being housed under heightened security measures. The facility is known for its use of protective custody for inmates considered at high risk within the general prison population.

Despite years of evaluations and court proceedings, Mitchell has continued to assert that his religious beliefs are divinely inspired — claims that were rejected by jurors during his trial.

The case has returned to public focus following the release of Netflix’s 2026 documentary Kidnapped: Elizabeth Smart, which revisits the investigation, the prosecution, and the long road to accountability. Elizabeth Smart, now an author and victims’ rights advocate, has continued to speak publicly about the importance of survivor protections and sentencing that reflects the lasting impact of violent crime.

More than two decades after her rescue, Smart has said she does not dwell on her captor — choosing instead to focus on advocacy, family, and helping others who have experienced trauma.

Kidnapping survivor, Elizabeth Smart who later became a bestselling author and national advocate. She now focuses on public speaking, survivor support, prevention work, and education through her foundation and published books.

Today, Elizabeth Smart is a bestselling author, a mother of three, and one of the most prominent victims’ rights advocates in the country. In the years since her rescue, she has built a life that extends far beyond the crime that once defined public attention.

Smart has been clear that she does not want her story to be framed around the man who kidnapped her. Instead, she has focused on speaking about survival, recovery, and what it means to reclaim a future after trauma.

In interviews, she has often returned to the same message — that even in the aftermath of unimaginable harm, healing is possible.

“Even after terrible things happen,” she has said, “you can still have a wonderful life.”

Brian David Mitchell encounters the Smart family while panhandling in Salt Lake City.

Elizabeth Smart’s mother, Lois Smart, offers him a small roofing job at the family’s home — a detail that later becomes central to the investigation.

Elizabeth Smart, 14, is abducted from her bedroom at knifepoint.

Her younger sister, Mary Katherine Smart, partially witnesses the kidnapping and hears the abductor’s voice.

Police are notified after Mary Katherine alerts her parents.

A large-scale search begins across Utah, quickly drawing national media attention.

Elizabeth is held captive in makeshift camps in the Utah foothills by Mitchell and his wife, Wanda Barzee.

Mitchell performs a mock “marriage” ceremony and begins repeatedly sexually assaulting Elizabeth.

Mitchell attempts to abduct Elizabeth Smart’s cousin by cutting through a bedroom window screen.

The attempt fails after a family dog begins barking.

Mitchell, Barzee, and Elizabeth travel between Utah and California.

Elizabeth is taken into public spaces while disguised in religious clothing but remains unidentified.

Mary Katherine Smart realizes the abductor’s voice matches a man the family knew as “Immanuel,” who had previously worked on their roof.

This recognition marks the first major investigative breakthrough.

Police release a composite sketch of the suspect based on witness recollections.

Mitchell’s family later provides photographs, which are distributed publicly.

Mitchell is featured on America’s Most Wanted, significantly increasing public awareness of his appearance and aliases.

Two separate couples recognize Mitchell walking in Sandy, Utah, with two women and contact police.

Elizabeth, disguised and using a false name, is taken into custody and later confirms her identity.

Mitchell and Barzee are arrested.

Mitchell and Barzee are formally charged with aggravated kidnapping, burglary, and sexual assault.

Court proceedings are repeatedly delayed due to mental competency evaluations, hospitalizations, and jurisdictional issues at both the state and federal levels.

Barzee pleads guilty to federal kidnapping charges and agrees to cooperate with prosecutors.

She is sentenced to 15 years in federal prison, with credit for time served.

Mitchell stands trial in federal court.

His defense argues insanity; prosecutors counter with evidence of planning and manipulation.

Mitchell is found guilty of interstate kidnapping and unlawful transportation of a minor with intent to commit sexual assault.

Mitchell is sentenced to life in federal prison without the possibility of parole.

Elizabeth Smart marries Matthew Gilmour and begins expanding her public work as a victims’ rights advocate.

Barzee completes her federal sentence and is transferred to Utah state custody to serve time related to the attempted kidnapping of Elizabeth’s cousin.

Barzee is released from prison after parole officials credit her federal and state confinement toward her sentence.

Elizabeth Smart publicly criticizes the decision.

Barzee lives under supervised release in Utah and is required to register as a sex offender.

Elizabeth Smart says in interviews that she does not think about her captors regularly and believes Mitchell should never be released.

Mitchell is transferred from USP Terre Haute in Indiana following reported inmate assaults.

He is moved to Federal Correctional Institution Lewisburg in Pennsylvania.

Netflix releases Kidnapped: Elizabeth Smart, featuring new interviews and reflections on the case more than two decades after her rescue.

Brian David Mitchell remains incarcerated in the federal prison system, where he is serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole.

Wanda Barzee has been released from custody but remains subject to sex offender registration requirements and court-imposed restrictions.

Elizabeth Smart continues her work as an author, advocate, and public speaker, focusing on survivor support, prevention efforts, and victims’ rights.

San Francisco Giants outfielder Jung Hoo Lee was briefly detained by U.S. border officials at LAX due to a paperwork issue. The incident did not involve an arrest or charges, but it highlights how U.S. Customs and Border Protection legally handles travelers during secondary inspection — a process that carries consequences even when resolved quickly.

Once Lee was referred to secondary inspection, border authorities were legally permitted to restrict his movement and verify admissibility without initiating any criminal or immigration proceedings.

When reports emerged that Jung Hoo Lee had been detained by immigration agents at Los Angeles International Airport, the phrasing alone suggested legal jeopardy. In reality, what occurred was a brief hold by border authorities over a documentation issue — a scenario that falls squarely within U.S. port-of-entry procedures rather than criminal or civil enforcement.

According to media reports, Lee was traveling from South Korea for a scheduled team event when he was stopped by U.S. Customs and Border Protection and placed into additional screening. The matter was clarified the same day, and Lee was released without charges.

Legally, however, the incident still represents a change in status: once a traveler is referred to secondary inspection, they are no longer simply “entering” the United States but are subject to expanded border authority. That distinction matters — not only for public figures, but for any traveler entering the country on a visa or work-related status.

Media reports state that Lee was stopped at LAX due to missing or incomplete paperwork connected to his entry. His team confirmed the issue was resolved quickly, and no further action was taken. There is no indication of arrest, criminal investigation, or immigration violation proceedings.

No prior immigration issues involving Lee have been publicly reported.

At U.S. ports of entry, border officials operate under a distinct legal framework. Travelers — including visa holders and lawful entrants — are subject to inspection authority that is broader than ordinary law-enforcement encounters inside the country.

Being “detained” in this context typically refers to secondary inspection, an administrative process used to verify identity, documentation, and admissibility. It does not require probable cause for a crime and does not trigger formal charges.

Under border inspection standards, officers may temporarily restrict a traveler’s movement, review documents, and ask detailed questions until admissibility is confirmed or denied.

Under border inspection standards, admissibility — not guilt — is the controlling legal question.

No. Available reporting indicates he was held for secondary inspection only. No arrest, charges, or detention order were issued.

At ports of entry, border officials have jurisdictional authority to determine admissibility. This allows temporary detention for verification purposes without meeting criminal charging thresholds.

It can. Incomplete or missing documents can delay entry, trigger additional review, or — in unresolved cases — result in refusal of entry. Resolution, as in this case, ends the process.

No. Constitutional protections apply differently at the border. Searches and questioning are permitted under border inspection standards that would not apply domestically.

Secondary inspections are logged administratively. While not criminal, repeated issues can affect future entries depending on circumstances.

This incident illustrates a common misunderstanding: being “detained” at an airport often reflects administrative verification, not legal wrongdoing. Millions of travelers are referred to secondary inspection each year for routine reasons ranging from paperwork discrepancies to random compliance checks.

The legal takeaway is that entry into the U.S. is not automatic, even for authorized travelers, until border officials complete their review.

From a legal process standpoint, airport detentions generally follow one of three routes:

Immediate clarification and release, as occurred here

Extended administrative review, potentially delaying entry

Refusal of entry, requiring return travel or follow-up through formal channels

These outcomes depend on documentation, admissibility standards, and verification results — not on celebrity status.

Jung Hoo Lee’s brief detention did not involve criminal or immigration enforcement action, but it underscores how U.S. border law functions in practice. Once referred to secondary inspection, travelers are legally subject to expanded authority until entry is approved.

For the public, the lasting significance is procedural: airport “detentions” are often administrative, but they still carry legal consequences that exist regardless of how quickly the issue is resolved — making preparation and documentation essential for anyone entering the United States.

Even when resolved quickly, secondary inspection represents a legally meaningful change in status — one that places travelers under expanded government authority until entry is formally granted.