Four people, including three children, were killed at a birthday gathering in Stockton, and the search for the attackers is still underway.

California are working through their investigation into a mass shooting at a birthday celebration in Stockton that left four people dead, including minors aged 8, 9 and 14, along with a 21-year-old adult.

More than ten other attendees were injured during the attack at a rented event hall in the city’s north end. Authorities continue to examine ballistic evidence and interview witnesses while no suspects have yet been identified.

The incident has prompted heightened public concern because of the number of children involved and the possibility that the shooters targeted someone at the gathering.

The case underscores ongoing public-safety challenges in California’s Central Valley, where interagency partnerships routinely address firearm-related crime. Investigators are now working to understand how the attackers accessed the venue and whether the event reflects broader patterns identified in California statistics on group-related violence.

Investigators say gunfire erupted inside the event hall during the early evening before extending into the surrounding area. Forensic teams recovered shell casings from both indoor and outdoor locations, as well as from vehicles struck during the incident. These findings will help determine how many firearms were used and whether the shooters moved through multiple positions.

In multi-scene shootings, California agencies typically combine video evidence, trajectory analysis and witness accounts to reconstruct an attack. That process remains underway as authorities work to establish the sequence of events and how the attackers left the area.

Evidence indicates the attack began indoors and rapidly extended outside, suggesting coordinated movement.

Authorities confirmed four fatalities: three children aged 8, 9 and 14, and a 21-year-old adult. More than ten additional attendees were taken to regional hospitals for treatment. Officials have not released the victims’ names pending next-of-kin notification.

Local schools activated crisis-support teams to assist students and families affected by the incident, following established protocols for traumatic events. Public-health analyses show that shootings at family celebrations are relatively uncommon, underscoring the severity of the attack and its impact across the community.

The ages of the victims have intensified public concern and expanded support efforts across local institutions.

Detectives say early evidence indicates the shooting was directed at specific individuals rather than random attendees. This assessment is based on initial interviews, ballistic patterns and risk indicators commonly associated with targeted violence.

Stockton and neighboring jurisdictions routinely monitor group-related disputes that can escalate when rival individuals meet unexpectedly at private gatherings. California’s legal framework allows for enhanced penalties in cases involving organized groups, though investigators have not stated whether those provisions may apply here.

Investigators believe the shooters had a specific objective, though the motive remains unconfirmed.

The manhunt remains active, with local deputies working alongside state and federal partners. Recovered casings and firearms will undergo tracing through national databases to identify prior recoveries or trafficking links. Multi-weapon cases can require significant laboratory time before investigators can match rounds to individual guns.

Authorities have urged residents and businesses to share security footage that may show vehicles or individuals connected to the attack. Rewards for credible information are being used to increase public cooperation in the investigation.

The search relies heavily on community submissions, firearm tracing and interagency coordination.

The shooting has renewed scrutiny of targeted gun violence in California’s Central Valley, where enforcement agencies and community groups have long collaborated on prevention strategies. Despite strict statewide firearm regulations, illegal gun movement remains a persistent challenge, particularly in regions facing concentrated group-related conflicts.

Incidents involving children often prompt reassessment of prevention initiatives, including early-intervention programs, school-based mental-health resources and cross-county intelligence sharing. The findings of the Stockton investigation may influence how state and local authorities prioritize future public-safety investments.

The attack highlights ongoing challenges in preventing targeted firearm violence, especially in high-risk communities.

How many people were killed?

Four fatalities were confirmed, including three minors and one adult.

How old were the victims?

The children were aged 8, 9 and 14; the adult was 21.

How many others were injured?

More than ten attendees were transported to hospitals with injuries.

Have investigators identified suspects?

No suspects have been publicly named.

Do officials believe the shooting was random?

Early findings suggest the attack was targeted.

The California birthday party shooting remains a major public-safety concern as investigators continue searching for those responsible and work to determine the motive behind the attack.

The deaths of three children have intensified community attention on school-based support, youth safety and regional violence-prevention strategies. As ballistic testing progresses and authorities review surveillance footage, the outcome of the investigation will shape policy discussions across the Central Valley. The incident underscores the continuing importance of coordinated public-safety efforts in addressing targeted gun violence.

If you need a clear breakdown of how California defines and prosecutes domestic violence, see our 2025 legal guide 👉👉 What Is Domestic Violence in California? The 2025 Guide to Understanding the Law, Your Rights, and the Real Consequences.

The New York Times has filed a federal lawsuit challenging new Pentagon rules that limit journalists to approved material and restrict independent reporting. The case argues the policy violates First Amendment protections and could reshape national standards for press access to government institutions.

The New York Times has sued the Pentagon in federal court, alleging that newly imposed media-access contracts unlawfully curtail journalists’ ability to gather and publish information about military affairs.

The lawsuit follows a sweeping policy shift overseen by Defense official Pete Hegseth that removed major news organisations from briefings unless they agreed to limit coverage to Pentagon-approved content. The restrictions were not confined to classified matters; they applied broadly to newsgathering, off-the-record exchanges and the publication of unreviewed material.

The challenge comes amid a visible transformation inside the briefing room, where legacy outlets have been replaced by ideologically aligned commentators.

Times reporter Julian Barnes and the newspaper are named as plaintiffs, represented by First Amendment lawyer Theodore Boutrous.

The complaint argues the rules amount to unconstitutional prior restraint and undermine the public’s ability to scrutinise decisions made within the Department of Defense. With the Pentagon declining immediate comment, the case raises fundamental legal questions about transparency, executive power and the role of independent reporting in national security oversight.

The New York Times is suing the Pentagon, arguing that new media-access rules introduced in October infringe on press freedoms protected by the Constitution. Journalists were seen leaving their offices that month as outlets evaluated whether to comply with the revised requirements.

The Times filed its lawsuit after the Pentagon introduced access contracts requiring reporters to limit coverage to pre-approved material and refrain from pursuing independent leads. Journalists who declined to sign—including CBS, ABC and The Washington Post—were removed from the briefing room.

This shift became apparent during the department’s third briefing of the year, held in a room largely populated by right-leaning online personalities. The Times argues that the restrictions interfere with constitutionally protected newsgathering and improperly condition access on compliance with content-based controls.

If successful, the lawsuit would block enforcement of the new rules and restore access for outlets that refused to sign.

Takeaway: The dispute centers on whether the Pentagon may require pre-approved reporting as a condition of attending its briefings.

The lawsuit invokes First Amendment protections that prohibit government agencies from restraining publication or conditioning access on content approval. Courts have long held that while officials may manage logistics and security, they cannot impose policies that suppress independent reporting.

At issue is whether the Pentagon’s agreements qualify as a form of prior restraint—typically defined as government action that prevents publication of lawful information. The Times argues the policy functions similarly by requiring pre-publication review and limiting scrutiny of military operations.

The court will examine whether the rules serve a compelling government interest, whether they are narrowly tailored, and whether less intrusive alternatives exist.

Takeaway: The case tests the boundary between permissible access management and unconstitutional censorship.

Agencies may regulate entry to secure areas, but courts scrutinise actions that restrict access based on viewpoint or impede independent reporting. Whether these rules constitute viewpoint discrimination will be central to the case.

They bar journalists from publishing unapproved information, which may place them within prior-restraint doctrine. Courts generally view such restrictions as constitutionally suspect.

Limits on informal exchanges can undermine newsgathering. Courts often treat restrictions on how journalists gather information as seriously as restrictions on publication itself.

Press-freedom cases directly affect how much independent information the public receives about military operations, budget decisions and national-security policy. Restrictive access rules may result in coverage that reflects only official narratives.

The case highlights the legal difference between protecting sensitive information and imposing administrative controls that suppress reporting across non-classified subjects. The outcome could influence how future administrations structure media access and whether agencies may require restrictive agreements as a condition for participation.

Takeaway: The ruling may affect the public’s ability to receive unfiltered reporting on national-security issues.

Best-case scenario:

A court could temporarily block the policy, restoring access to all outlets while the case proceeds. Agencies sometimes revise disputed rules to avoid prolonged litigation.

Worst-case scenario:

The court could uphold the contracts, giving agencies wide latitude to condition press access on adherence to internal communication controls.

Most common procedural pathway:

Access cases often turn on constitutional arguments rather than extensive factual disputes, meaning the court may resolve the matter through motions rather than a full trial.

Takeaway: Judges will focus on whether the Pentagon’s policy burdens press rights beyond what the Constitution allows.

Why were mainstream organisations removed from briefings?

They declined to sign contracts requiring reporting to be limited to Pentagon-approved material.

Is the lawsuit only about the Times?

The Times is the plaintiff, but its arguments apply broadly to all news organisations seeking equal access.

Can the Pentagon set reporting rules for journalists?

Agencies may set ground rules for location and security, but courts examine closely any policy that restricts lawful newsgathering.

Will this affect other federal agencies?

The ruling may influence how other departments craft press-access policies, especially where prior-restraint concerns are raised.

The New York Times’ lawsuit against the Pentagon marks a pivotal clash over government control of public information. At stake is whether officials may tie access to pre-publication review and restricted reporting. The case now moves to federal court, where judges will consider how far the First Amendment limits agency power and whether the Pentagon’s policy undermines the public’s right to independent oversight. The outcome could reshape national standards for press access across government.

The identification and arrest of a Virginia man in the January 6 pipe bomb case affects an ongoing federal investigation and public understanding of a long-unresolved national security incident.

Federal agents have arrested Brian Cole, a 30-year-old resident of Woodbridge, Va., in connection with the pipe bombs placed near the Democratic National Committee and Republican National Committee headquarters on Jan. 5, 2021.

The arrest occurred early Thursday as law-enforcement teams executed warrants at a suburban home, ending a years-long nationwide search for the individual seen on security footage walking through Capitol Hill the night before the attack on the U.S. Capitol.

Images posted online showed a heavy police presence around the residence as FBI personnel processed evidence.

The case is significant because the devices were discovered just hours before crowds gathered at the Capitol, prompting heightened security concerns and years of unanswered questions.

Cole’s arrest gives investigators an opportunity to test earlier theories, re-evaluate digital and physical evidence and examine how federal agencies handled one of the most complex domestic investigations since the Boston Marathon bombing.

The arrest follows a recent FBI push that included a $500,000 reward for information on the person who placed devices near the Democratic and Republican National Committee headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Cole is a Virginia resident whose name surfaced publicly for the first time on Thursday when federal officials announced the arrest. Woodbridge, the suburb where he was taken into custody, has grown rapidly in the past decade as Washington’s commuter belt expanded, and many residents travel to federal workplaces in the region.

Public records in similar federal cases have often revealed limited background information until initial court filings become available, which outline charges, alleged conduct and procedural history.

Investigations tied to improvised explosive devices frequently begin with basic demographic details before expanding into work history, travel patterns or financial records.

In past FBI cases involving homemade explosives, such details emerged gradually as courts unsealed documents, allowing the public to see how investigators traced earlier material links.

Takeaway: Public understanding of Cole’s background will likely develop as court records become available.

Images shared on social media showed a large police presence outside Cole’s home in the Woodbridge, Va., suburb.

The FBI has spent years evaluating the surveillance footage captured across several blocks of Capitol Hill the night the bombs were placed. The videos showed a hooded figure walking from South Capitol Street toward both national party headquarters, setting down items before leaving the area. Although the footage gained widespread attention, investigators said early analyses yielded few identifiable traits because the suspect wore a face mask, gloves and distinct but commercially available athletic shoes.

Federal cases involving delayed arrests typically involve a renewed assessment of earlier leads, including retailer records, location data and interviews conducted shortly after the event. In previous high-profile domestic investigations, arrests occurred only after agents revisited older evidence using improved analytic tools.

Takeaway: Cole’s identification appears to follow a pattern where older materials become more useful as forensic and digital methods advance.

The devices were built using threaded galvanized pipes, kitchen timers and black powder, according to investigators. One of the recovered bombs is shown above.

The pipe bombs, which were made from galvanized pipes, kitchen timers and black powder, prompted a rapid response from the FBI, U.S. Capitol Police and explosives technicians on Jan. 6, 2021.

The discovery required evacuations near both party headquarters and briefly redirected resources at a time of heightened emergency. Federal agencies later described the incident as one of the most complex improvised explosive device investigations since 2013, citing the overlapping crises unfolding that day.

Authorities have long warned that simple components can still pose significant risks, which is why agencies periodically release advisories on common materials used in homemade devices. In prior domestic cases, similar construction methods complicated efforts to trace items to a specific purchaser or manufacturer.

Takeaway: The bombs’ basic construction contributed to the prolonged difficulty in determining who built and placed them.

Interest in the case grew as the investigation extended beyond its first year, with online communities attempting to identify the masked individual through gait analysis and video comparison.

Several individuals were mistakenly identified by commentators, reflecting a broader trend in which high-profile cases spur public attempts at parallel investigations. False claims have appeared in other major federal cases in the past decade, prompting attorneys and officials to warn about the potential harms of premature attribution.

Federal investigators have generally emphasized that only court records and official statements should be treated as authoritative. In previous domestic security investigations, similar waves of speculation complicated public understanding as agencies continued their work.

Takeaway: Cole’s arrest provides a clearer foundation for public information after years of speculation.

The identification of a suspect in the pipe bomb case arrives as federal courts continue to process hundreds of cases related to the Capitol attack.

Although the pipe bombs were discovered before crowds reached the Capitol, their placement contributed to national security concerns that intensified the response. The arrest may prompt congressional interest in how the case evolved and whether earlier evidence could have been interpreted differently.

Federal investigations involving coordinated political targets often lead to broader reviews of security practices, including guidance for federal facilities and party organizations. Similar reviews followed incidents in 2018 and 2020 in which mailed explosive devices targeted political figures.

Takeaway: The arrest adds new detail to the broader examination of security vulnerabilities exposed in early 2021.

Was anyone injured by the pipe bombs?

No. The devices were located before detonation and were rendered safe by explosives experts.

Why did it take nearly five years to identify a suspect?

The components were common, early data comparisons were inconclusive and investigators required time to re-evaluate evidence gathered in 2021 and 2022.

Is Cole connected to the broader events of January 6?

Authorities have not indicated any link beyond the placement of the devices the night before the attack.

What happens next in the case?

Further details are expected in initial court filings, which typically outline charges and factual allegations.

Will more information about Cole become public?

Yes. Background information generally becomes available through court documents and official statements as the case proceeds.

Brian Cole’s identification in the January 6 pipe bomb case marks a significant shift in a long-running federal inquiry that has remained a point of public concern.

The arrest matters because the devices contributed to early security strain on a day shaped by multiple emergencies. As charges are filed and records become public, more detail about Cole's background and alleged actions will inform ongoing discussions about domestic security, investigative capacity and accountability tied to the January 6 events.

During a reunion episode of The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives, Jessi Ngatikaura tearfully said she had recently uncovered a memory of being raped at 19 during therapy.

Her revelation prompted a broader cast conversation about trauma, intimacy, and healing. While no legal action has been announced, her disclosure highlights the complex legal and procedural issues surrounding survivor reporting and televised statements.

The reunion special for The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives took an unexpectedly emotional turn when influencer Jessi Ngatikaura, already navigating a high-profile marital crisis on the series, disclosed that she had recently uncovered a memory in therapy of being raped at age 19.

The revelation came during a cast conversation about intimacy, chronic illness, and the long-term impact of childhood trauma, after costar Mikayla Matthews shared her own history of abuse.

What began as a discussion about relationships shifted into a raw and unfiltered examination of how past harm can shape adult connection — and how televised disclosures carry legal, psychological, and public ramifications.

The moment landed heavily in the studio. Host Stassi Schroeder paused the conversation as Jessi fought back tears, explaining how her therapeutic work around her marriage had resurfaced memories she had not previously articulated.

No complaint, report, or legal filing has been announced, but her statement — broadcast to a national audience — raises sensitive questions about the rights of survivors, the responsibilities of media platforms, and the legal frameworks that surround delayed recall of trauma.

The emotional stakes were clear: cast members cried, spouses reflected, and viewers witnessed the difficult intersection of personal history and public storytelling.

Jessi Ngatikaura and her husband Jordan

The reunion episode centred on the cast’s ongoing discussions about intimacy and emotional health. As Mikayla Matthews described returning to therapy to address the lingering effects of childhood abuse, Jessi Ngatikaura became visibly emotional and said she had uncovered, through therapy, a memory of being raped when she was 19.

No legal action has been initiated or reported. Her disclosure was presented as part of a therapeutic process connected to broader marital struggles documented throughout season 3. Jordan, her husband, has publicly acknowledged emotional conflict in their relationship, while both have spoken about working through their issues in counselling.

The cast’s response underscored the seriousness of the moment. Costar Conner, who previously shared his own history of childhood sexual assault, connected with Jessi’s comments and discussed the ways unprocessed trauma can affect adult intimacy. The conversation unfolded without accusations toward named individuals, focusing instead on the emotional weight of recovery.

Although Jessi has not reported the incident to law enforcement, her public disclosure intersects with several key legal areas:

Survivor reporting rights: In most jurisdictions, adults who disclose past sexual assault retain the right to report the incident to police at any time, subject to statutes of limitation. These laws vary widely by state and may be extended or eliminated for certain categories of sexual offences.

Delayed recall and trauma: Courts generally treat memory-related disclosures with caution. Trauma specialists often note that fragmented or delayed memories can occur, but legal systems typically require corroborating information if a case is formally pursued. This principle is procedural, not an assessment of credibility.

Televised disclosures: When a survivor speaks publicly on a broadcast platform, their statements can raise issues related to privacy, potential media scrutiny, and the emotional impact of public reaction. However, a televised disclosure does not itself initiate a legal process.

Reporting pathways: If a survivor decides to come forward, the process typically begins with a police report, followed by interviews, evidence review, and potential prosecutorial assessment. These steps are universal and do not imply any action in Jessi’s situation.

If she chooses, she may file a report with local law enforcement. Whether a case can proceed depends on jurisdictional statutes of limitation and procedural criteria. There is no indication she intends to take that step.

Generally, no. Publicly sharing a personal experience does not replace or prejudice formal reporting. It may, however, increase public visibility and emotional stakes for the survivor.

Courts assess all testimony through established evidentiary standards. Delayed recall is not uncommon in trauma cases, but legal systems typically require additional evidence before charges are considered.

Broadcast networks often have duty-of-care protocols when sensitive content arises, including psychological support access. These are industry standards rather than legal obligations unless contractual terms specify otherwise.

No individual was named. Without specific allegations against an identified person, no legal exposure is created by the disclosure itself.

Many survivors delay reporting for years due to trauma, lack of support, or fear of consequences. Understanding that the law does not require immediate disclosure is important. Statutes of limitation define how long prosecutors can bring a case, and these timelines vary dramatically, with some states allowing adult survivors to report decades later.

Therapy often plays a central role in recovery. When a disclosure arises in a therapeutic setting, survivors may choose to discuss legal options with a trained advocate or attorney before deciding on next steps. Public conversations — whether online or on television — do not create legal obligations but can influence a survivor’s emotional experience and social environment.

These principles apply broadly, regardless of celebrity status, and help illuminate how personal trauma can intersect with public narrative in the digital age.

Jessi retains full autonomy over whether to seek legal counsel, file a report, or continue addressing the matter privately through therapy. She faces no procedural deadlines unless a statute of limitation applies.

If she chose to pursue legal action and the statute of limitation for the offence had expired, prosecutors would generally be unable to proceed. This is a structural limitation of criminal procedure, not an evaluation of her account.

Many survivors continue therapy, gather support, and optionally consult legal advocates to understand their rights. Some choose to report; others opt for non-legal healing routes. Each path is personal and legally neutral.

Is Jessi making a legal accusation?

No. She described a personal memory uncovered in therapy but did not identify any individual or initiate a complaint.

Could the revelation affect her marriage storyline legally?

No legal implications arise from the disclosure itself. The emotional impact, however, is part of the show’s documented narrative.

Does public disclosure change legal deadlines?

No. Statutes of limitation operate independently of media statements. Only a formal report triggers legal evaluation.

Can televised statements be used in a future legal process?

Potentially, but only as part of a broader evidentiary record if a survivor chooses to pursue a case. That decision rests entirely with the survivor.

Jessi Ngatikaura’s emotional disclosure on the reunion special does not constitute a legal case, but it places a public spotlight on the complex legal and procedural terrain surrounding adult survivors who reveal past trauma years later.

For now, her statement remains a personal account shared in a therapeutic and broadcast context. The next steps — whether private, therapeutic, or legal — rest solely with her. What the reunion underscored is the growing visibility of survivor narratives and the legal considerations that arise when deeply personal experiences are shared in the public eye.

Growing pneumonia admissions are affecting older adults and people with underlying health conditions across the UK.

Pneumonia cases continue to attract public concern after recent hospitalisations, including that of 63-year-old Wayne Lineker, highlighted how quickly respiratory infections can escalate.

Health data from England and Wales shows that pneumonia and influenza remain significant contributors to seasonal illness and mortality, particularly among older adults.

Clinical records released this year confirmed pneumonia as the underlying cause in the deaths of actors Val Kilmer and Diane Keaton. Health officials say the pattern reflects long-term trends rather than a single cause, with winter surges influenced by circulating viruses, age-related vulnerability and existing medical conditions.

Wayne Lineker revealed he was hospitalised after contracting pneumonia

The issue matters for public health because pneumonia remains one of the most common reasons for emergency respiratory admissions.

The illness can develop from several types of infections and environmental exposures, and it strains services when flu activity is high. Understanding how pneumonia forms—and who is most at risk—helps shape prevention campaigns, vaccination planning and guidance for when people should seek care.

The rise in cases also underscores long-standing concerns about respiratory resilience in ageing populations and the role of early treatment in preventing severe complications.

Clinicians note that pneumonia often follows other respiratory infections, including seasonal influenza. The relationship is well documented: flu can weaken the airway’s natural defences, allowing bacteria to reach the lungs.

The Office for National Statistics recorded more than 23,000 deaths in 2024 in England and Wales where influenza and pneumonia were listed together as the underlying cause, reflecting how commonly the two conditions overlap. International research has shown similar patterns after severe flu years, with post-viral pneumonia contributing to excess winter mortality.

Takeaway: rising pneumonia numbers are closely linked to broader seasonal respiratory trends, especially influenza circulation.

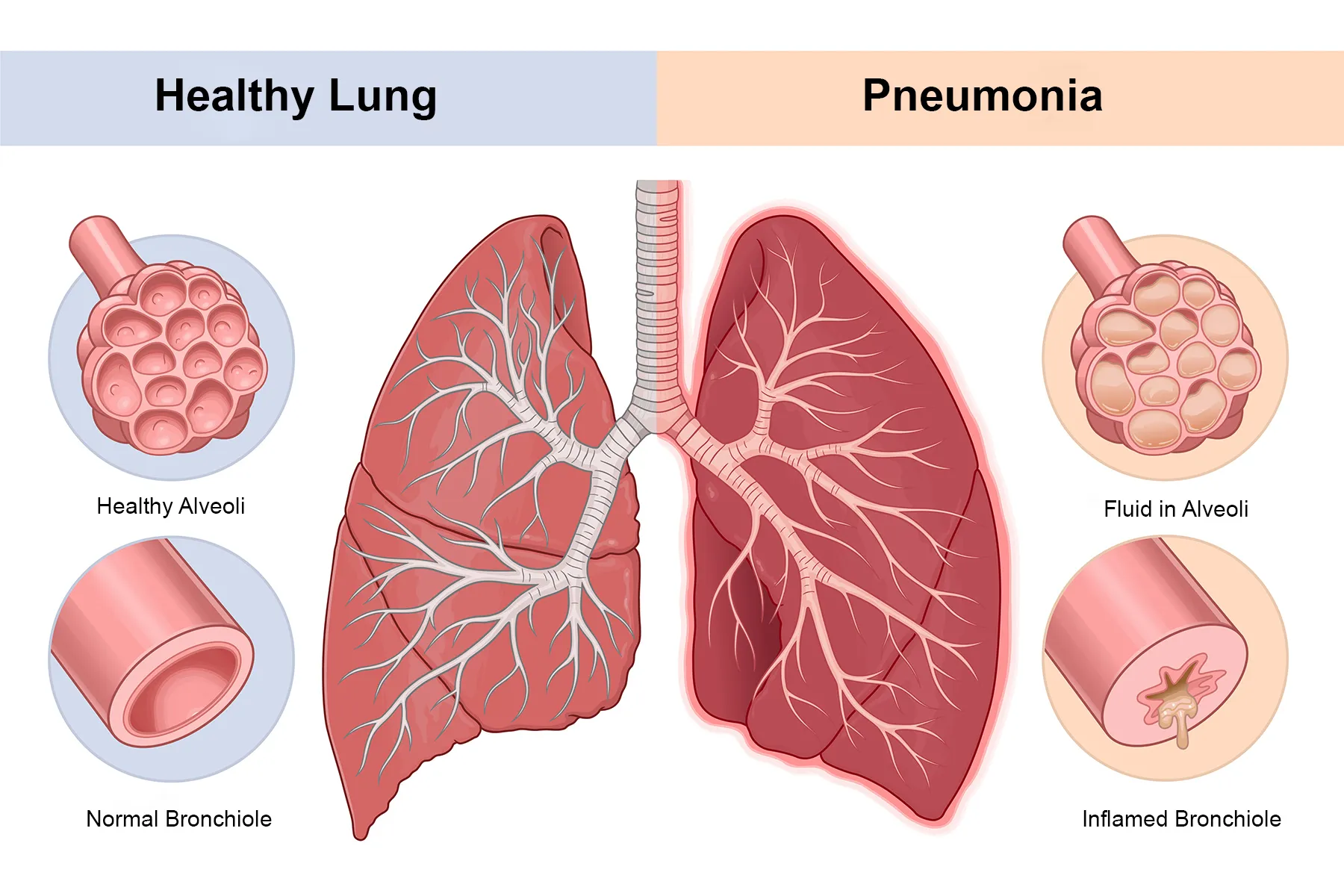

Pneumonia occurs when the air sacs of the lungs become inflamed and fill with fluid or debris, limiting oxygen exchange.

Common causes include bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, viruses including influenza and RSV, and less frequent sources like fungi. In some cases, aspiration of food or stomach contents can trigger a chemical or bacterial infection.

Global health agencies note that tuberculosis and water-related incidents, including near drownings, can also lead to lung inflammation classified as pneumonia. Treatment depends on the specific cause, and diagnostic testing has become more widely available in recent years to help clinicians tailor care.

Takeaway: pneumonia is a lung inflammation with multiple proven causes rather than a single, uniform illness.

Ageing reduces immune responsiveness and lung elasticity, making it harder to clear pathogens. Frailty, chronic conditions and reduced physical activity can increase the likelihood of infection.

Public health bodies across Europe have reported that older adults have the highest rates of pneumonia-related hospital admission. Vaccination programmes targeting influenza and pneumococcal disease are designed to protect this group, though uptake varies by region. Similar challenges are observed in countries with rapidly ageing populations, including Japan and Italy, where pneumonia prevention is a major health priority.

Takeaway: older adults are disproportionately affected because age-related changes make the lungs and immune system less resilient.

Without timely treatment, pneumonia can cause respiratory failure or lead to sepsis, which occurs when infection enters the bloodstream.

The UK Sepsis Trust and NHS guidance emphasise rapid response because early intervention reduces the likelihood of organ damage. While severe cases often require ventilation or intensive care, many people with mild pneumonia recover at home with rest, fluids and medication. Digital triage tools and expanded urgent care centres have helped clinicians identify when imaging or hospital evaluation is needed.

Takeaway: complications emerge when infection spreads or breathing becomes impaired, making early assessment essential.

Health authorities advise several evidence-based steps: getting recommended vaccines, stopping smoking, staying physically active, and managing conditions such as diabetes and heart disease.

Hospitals also follow strict ventilation and surgical protocols to reduce pneumonia associated with medical procedures. Global studies suggest that recovery timelines vary widely, with fatigue and cough often lasting weeks even after treatment. Most people who recover from pneumonia do not face an increased lifetime risk unless other long-term factors are present.

Takeaway: prevention and recovery depend on overall health, vaccination and prompt treatment decisions.

Is pneumonia contagious?

Some types are. Bacterial and viral pneumonia can spread through droplets, while aspiration and chemical pneumonia cannot.

How is pneumonia diagnosed?

Doctors typically use symptoms, chest exams, imaging such as X-rays and, when needed, blood or sputum tests to identify the cause.

Can pneumonia be treated at home?

Yes, mild cases may be managed with rest and prescribed medication, but severe symptoms require urgent medical evaluation.

Do vaccines prevent pneumonia?

Influenza and pneumococcal vaccines reduce the risk of the most common forms of pneumonia, especially in older adults.

How long does recovery take?

Recovery varies but often ranges from a few weeks to several months depending on age, severity and underlying health.

Pneumonia remains a significant public health concern because it develops from many sources and disproportionately affects older adults.

The condition places sustained pressure on health systems during periods of high flu activity, and cases such as Wayne Lineker’s highlight how suddenly symptoms can escalate. Clear guidance, timely care and vaccination remain the most effective tools for reducing illness. Continued monitoring of pneumonia trends will help authorities adapt prevention strategies and communicate risk more effectively.

👉👉 Gary Lineker Lands Multi-Million-Pound Netflix Deal for 2026 World Cup Podcast 👈👈

👉👉 Simon Jordan Returns To Watch Crystal Palace After 15-Year Absence 👈👈

Millions of AT&T customers may qualify for compensation after two major data breaches exposed personal information in 2024.

AT&T customers have only days left to submit claims for payments from a $177 million settlement tied to two data breaches disclosed in March and July 2024, with the final deadline set for Thursday, Dec. 18. The incidents exposed account passcodes, Social Security numbers and call and text metadata, leading to consolidated federal litigation and a nationwide settlement fund. Court filings show a rise in claim submissions following publication of the revised deadline.

The case is significant for consumers because the breaches involved sensitive identifiers that can persist on criminal marketplaces for years, according to guidance from the Federal Trade Commission. This increases the long-term risk of identity misuse. Customers who believe they were affected are encouraged to confirm eligibility and file before Dec. 18 to ensure they are included.

The March 30, 2024 breach led to the appearance of customer details — including addresses, Social Security numbers and passcodes — on monitored dark-web forums.

The July 12, 2024 breach involved unauthorized downloads of call and text metadata from AT&T systems.

AT&T and court filings state that more than 65 million current and former customers across 2019–2024 may have been affected.

Following the first breach, AT&T initiated a broad passcode reset for millions of users as a security measure.

Takeaway: The two breaches exposed different categories of information, expanding the pool of eligible claimants.

AT&T has maintained that it disputes the allegations but chose settlement to avoid extended litigation.

Consumer advocates have advised affected users to review their credit reports and watch for phishing attempts referencing the breaches.

State attorneys general issued reminders in 2024 urging residents to confirm the authenticity of settlement notices to avoid scams.

Takeaway: Community guidance stresses caution and use of verified settlement resources as the deadline nears.

Eligible customers may receive tiered cash payments or reimbursement for documented financial losses, depending on which breach affected them.

The structure mirrors recent settlements involving large technology and telecom firms, where compensation levels vary by sensitivity of exposed data.

Privacy researchers have noted that metadata, even without message content, can reveal patterns about an individual’s communication habits.

Large breach settlements, such as those involving credit bureaus, have shown surges in participation as filing deadlines approach.

Identity Theft Resource Center data shows U.S. data compromises rose sharply in 2023 and remained elevated in 2024, with telecom companies reporting multiple targeted incidents.

The ITRC’s comparative analyses indicate that breaches involving Social Security numbers present the highest long-term identity risks.

Takeaway: National data situates the AT&T breaches within broader trends of rising cyber incidents affecting sensitive identifiers.

Customers can file claims online at telecomdatasettlement.com, where instructions and eligibility tools are provided.

Mail-in claims must be postmarked by Thursday, Dec. 18 and sent to the address listed by Kroll Settlement Administration.

The administrator’s website includes a lookup feature to confirm whether an account was included in either breach.

Most customers will need the notice ID and confirmation code included in AT&T’s earlier notifications.

Takeaway: Filing options are accessible online and by mail, with tools available to confirm account eligibility.

Customers affected in either the March 30 or July 12, 2024 breaches—and some in both—are eligible. AT&T reports more than 7 million affected in the March incident and over 65 million potentially affected between 2019 and 2024 in the July incident.

Customers may receive up to $5,000 for verified financial losses from the March breach and up to $2,500 for losses linked to the July breach. Tiered payments are also available for those without documented losses, with higher tiers for customers whose Social Security numbers were exposed.

Only those seeking documented-loss payments must provide evidence such as receipts or bank statements. Tiered payments do not require proof of losses.

Payments are expected to be made either digitally or by check after the court grants final approval of the settlement. Distribution will follow verification of all claims.

The settlement website provides an eligibility lookup tool, and the administrator offers a toll-free number for assistance.

The claims period closes on Thursday, Dec. 18.

The court will then review the settlement for final approval before payments are processed.

AT&T must continue certain agreed-upon security practices for a defined period, according to settlement filings.

Takeaway: After Dec. 18, the process shifts to final court approval and payment administration.

Consumers affected by AT&T’s 2024 data breaches have until Thursday, Dec. 18 to seek compensation. The settlement provides tiered payments and reimbursement options depending on the type of data exposed and whether customers experienced measurable losses. Because sensitive identifiers were involved, timely participation matters for long-term financial protection. Customers should verify their eligibility and monitor upcoming court actions that will determine when payments are issued.

👉 Learn how California Class Actions for Defective Products help consumers pursue compensation when everyday items malfunction or pose safety risks.

The settlement offers compensation to people whose personal and health-related data was exposed in the 2020 EyeMed cyber incident.

EyeMed Vision Care has agreed to a $5 million class action settlement after a 2020 cybersecurity incident exposed personal information belonging to consumers across the United States. Court filings surfaced in federal court in Ohio, where the case has been underway since early 2021. The settlement applies to individuals who previously received a breach notification from the company confirming their data was involved in the June 2020 event.

The breach matters because it involved sensitive identifiers commonly targeted in identity-related fraud, including dates of birth and government-issued numbers. The case comes at a time when health-related data breaches continue to rise; the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reported more than 700 healthcare cybersecurity incidents in 2023. The EyeMed settlement outlines reimbursement options, deadlines, and expanded protections for those affected.

The 2020 incident began when an unauthorized third party accessed a webmail account linked to EyeMed’s operations, according to regulatory filings submitted to state attorneys general.

Data involved included names, contact information, policy numbers and, in some cases, government identifiers such as Medicare or Medicaid numbers.

The breach occurred in June 2020, and EyeMed began issuing breach notifications later that year, as required under state and federal privacy laws.

EyeMed serves more than 100 million members globally, and the company reported the breach to the U.S. Office for Civil Rights, which tracks incidents involving medical information.

Takeaway: The settlement addresses an incident that triggered mandatory reporting to both regulators and consumers.

EyeMed stated in regulatory filings that it enhanced security controls after discovering the breach and worked with law enforcement during the investigation. The company has not admitted wrongdoing as part of the settlement.

Consumer reactions have mirrored concerns seen in other medical-sector breaches, particularly around the long-term risks associated with compromised identification numbers that cannot be changed.

State attorneys general, including in New York and California, previously cited the importance of timely breach notifications and updated security practices in similar healthcare-related incidents, providing broader context for consumer expectations.

Takeaway: The response has focused on transparency, regulatory compliance, and long-standing consumer concerns about medical data protection.

Consumers who received a breach notice can request reimbursement for out-of-pocket costs tied to fraud, identity theft or credit monitoring. This aligns with compensation seen in other recent healthcare settlements, such as those involving insurers and hospital networks.

For people managing health benefits, the case highlights how breaches involving medical identifiers can create risks that persist for years, since many government-issued numbers cannot be replaced easily.

The settlement also arrives as federal agencies report increased cyber activity targeting insurance and benefits providers, underscoring the wider public interest in data security across health-related platforms.

Takeaway: Affected individuals gain access to financial remedies at a time of heightened cybersecurity concerns across the healthcare sector.

HHS breach statistics show that incidents involving health plans have increased steadily since 2018, with hacking events accounting for the majority of large breaches reported under HIPAA. These figures help explain why settlements in this sector often include compensation for credit monitoring and identity-theft mitigation.

Comparatively, the median size of healthcare data breaches in 2023 exceeded 90,000 affected individuals, according to the HHS breach portal.

Takeaway: Public data shows a rising trend in healthcare-related cyber incidents, placing the EyeMed breach within a much broader pattern.

Consumers eligible for compensation must submit a claim through the official settlement website, EyeMedDataSettlement.com. The site provides forms, documentation requirements and instructions for uploading receipts or proof of loss.

Claims can be filed online or by mail through the settlement administrator, Kroll Settlement Administration LLC. The filing period remains open until Dec. 11, 2025.

Participation does not require any subscription or additional service. All necessary materials are publicly accessible.

Takeaway: Affected individuals can file claims directly through the official portal with no added costs.

Only individuals who received an official EyeMed breach notice relating to the June 2020 incident are eligible. Notices were distributed under state privacy laws, which require companies to contact consumers when certain forms of data are exposed. Eligibility is limited to those specific notifications.

The settlement provides reimbursement for up to $10,000 in documented losses related to fraud, identity theft, or professional fees. It also offers up to four hours of lost-time compensation at $25 per hour, plus a residual cash payment estimated at around $50 depending on total claims.

Documentation is required for out-of-pocket reimbursement, such as bank statements, credit bureau reports, invoices or receipts. Lost-time compensation does not require the same level of documentation but must be claimed truthfully.

A federal judge has granted preliminary approval. Final approval will be considered at a hearing on Jan. 7, 2026. Payments will proceed only if the settlement receives full approval.

Processing times vary across class action settlements. Payments typically begin after final court approval and resolution of any appeals.

The exclusion and objection deadline is Nov. 11, 2025. Claim submissions close on Dec. 11, 2025.

A final approval hearing is scheduled for Jan. 7, 2026, in the Southern District of Ohio.

If the court grants final approval, distribution of payments will begin after administrative processing.

Takeaway: The next major step is the January 2026 approval hearing, which will determine when payments can begin.

The EyeMed settlement offers compensation to people whose medical and personal information was exposed in a cyber incident affecting a major vision benefits provider. The case underscores continuing concerns about data security in the healthcare sector, where breaches can involve identifiers that are difficult to replace. For affected individuals, the settlement provides a route to recover costs tied to fraud or identity-theft risks. Deadlines and documentation requirements make early action important for those planning to file.

The update brings Nickelodeon’s 2000s-era animated series Danny Phantom to Fortnite players worldwide through new, purchasable in-game cosmetics.

Epic Games will introduce Danny Phantom to Fortnite’s rotating Item Shop on December 5, expanding the game’s portfolio of licensed characters from major entertainment brands.

The company confirmed the release in an official promotional post outlining upcoming cosmetic rotations. The update includes a playable version of Danny in both his human and ghost forms, plus an outfit based on Sam Manson, one of the series’ central characters.

The addition reflects Fortnite’s continued strategy of integrating legacy television properties that appeal to multiple age groups.

Nickelodeon series have become a recurring part of Epic Games’ licensing partnerships, and players often look to these collaborations for both nostalgic value and new in-game customization options. The timing also aligns with broader seasonal updates that typically bring increased player activity.

Epic Games said the collaboration will appear in the Item Shop beginning December 5, following routine daily updates to the store. Item Shop releases operate globally and rotate at set times, which allows players across regions consistent access to new cosmetics. While Epic has not published pricing, licensed outfits in similar collaborations often follow established tiers listed in Fortnite’s public documentation.

The release confirms continued expansion of the game’s cross-media licensing portfolio.

Takeaway: The release date is set, while pricing and bundle details will follow standard Item Shop practices.

Danny’s outfit includes two selectable styles based on his human and ghost appearances from the original Nickelodeon series, according to Epic’s announcement. Sam Manson appears in a single style. Multi-style designs are common in Fortnite’s licensed sets, particularly when characters have distinct forms or recognizable alternate looks.

Fortnite’s previous collaborations with Nickelodeon properties—such as Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles—followed a similar release model, offering character-based cosmetics without competitive advantages.

Takeaway: The character designs follow Fortnite’s typical approach of providing cosmetic variety without gameplay differences.

Nickelodeon’s Danny Phantom, which aired from 2004 to 2007, remains a recognizable franchise among players who grew up during the network’s early-2000s programming era. Although the series has not had a reboot, its characters continue to appear in licensed media such as crossover video games and streaming anthologies.

Fortnite’s collaborations with older animated properties reflect a broader industry trend of repackaging archival franchises to attract both older viewers and new audiences through live-service games.

Takeaway: The collab leverages nostalgia and cross-platform media recognition.

Epic Games has steadily expanded its roster of licensed characters to include musicians, athletes, film franchises, and animated series. These partnerships are typically announced through the company’s social channels rather than through third-party leaks, reflecting Epic’s controlled rollout strategy.

Analysts have noted that these partnerships help sustain engagement in free-to-play ecosystems, particularly during major seasonal transitions.

Takeaway: The release is part of a long-term strategy to integrate widely recognizable entertainment brands into Fortnite’s rotating content model.

Fortnite players often monitor official Epic channels, including the company’s status page and Item Shop announcements, to confirm drop times. Cosmetic sets typically appear when the shop refreshes at 00:00 UTC, though regional visibility may vary slightly due to platform-specific updating.

Takeaway: The safest source for timing and availability is Epic’s daily Item Shop update.

When does the Danny Phantom Fortnite skin release?

Epic Games says it will be available on December 5 in the Item Shop.

Will Danny have multiple selectable styles?

Yes. Epic confirmed human and ghost forms for the character.

Is Sam Manson included?

Yes. Sam will appear as a separate outfit with one confirmed style.

Are prices available yet?

Epic has not released pricing, but licensed cosmetics typically follow existing Item Shop tiers.

Does the collab affect gameplay?

No. Fortnite’s licensed skins are cosmetic only.

Epic Games’ December 5 rollout of the Danny Phantom Fortnite collab adds another recognizable Nickelodeon series to the game’s expanding catalogue of licensed properties.

The update gives players cosmetic options with no competitive impact while continuing Fortnite’s long-term strategy of integrating established entertainment brands. With the core keyword Danny Phantom Fortnite collab now confirmed by Epic, players can expect standard Item Shop access and additional details as the cosmetics decrypt. The collaboration underscores how legacy media franchises continue finding new relevance inside live-service games.

Tosin Adarabioyo’s second-half mistake allowed Leeds United to extend their lead and deepen Chelsea’s gap in the Premier League title race.

Leeds United defeated Chelsea 3–1 at Elland Road on Wednesday after a defensive error from Tosin Adarabioyo handed the hosts a decisive third goal. Leeds had already established control through Jakob Bijol’s early header and Ao Tanaka’s long-range strike, while Pedro Neto briefly pulled one back for the visitors. The loss leaves Chelsea nine points behind league leaders Arsenal as the winter schedule intensifies.

The moment involving Adarabioyo came during a spell when Chelsea were regaining structure after halftime changes. Against a Leeds side deploying an aggressive press, the defender’s hesitation in his own box reflected the risk Premier League teams face when building out from deep under pressure.

The critical moment arrived shortly after the hour mark when Adarabioyo received a routine pass inside his penalty area. Pressed immediately by Noah Okafor, he delayed his clearance, and the loose ball ran across goal for Dominic Calvert-Lewin to finish from close range. Leeds’ pressure mirrored a broader tactical theme this season, with high pressing contributing to a rising share of goals generated from turnovers in defensive zones across the league.

Takeaway: A brief hesitation under pressure turned a manageable deficit into an uphill task for Chelsea.

Chelsea have maintained strong defensive numbers from open play, but their buildup has produced several high-cost mistakes in recent months. Clubs that rely on circulating possession through central defenders—common across the Premier League—often struggle when opponents commit multiple players to the press. With Wesley Fofana still unavailable, Adarabioyo has taken on a larger role in a back line still adapting to Enzo Maresca’s positional structure.

Historical league data shows that newly integrated defenders often face an extended adjustment period when transitioning to possession-dominant systems.

Takeaway: Chelsea’s defensive setup continues to carry risk when opponents press aggressively in the first phase.

Leeds opened the match with sustained pressure, producing several early attempts and earning multiple set pieces before Bijol headed in the opener. Their pressing triggered turnovers across midfield and forced Chelsea into deeper positions than usual. This approach reflects a league-wide trend in which mid-table sides use coordinated pressing to disrupt teams that prefer slow buildup play.

Elland Road’s strong home form this season has been supported by consistent crowd intensity, contributing to Leeds’ ability to force mistakes in high-pressure moments.

Takeaway: Leeds’ coordinated early pressure shaped the match and reduced Chelsea’s margin for error.

Pedro Neto’s early second-half goal briefly shifted momentum, suggesting Chelsea could mount a response. But the defensive lapse soon after diminished that opportunity and highlighted concerns about the team’s ability to manage physical contests on the road. With fixtures against title rivals approaching, Chelsea’s focus will likely centre on reducing technical errors in deep areas.

Historical precedent shows that clubs in tight top-four races often rely on defensive consistency rather than attacking output to secure late-season points.

Takeaway: Chelsea must tighten their defensive execution to maintain their top-four position.

What happened during Tosin Adarabioyo’s error?

He hesitated when receiving the ball inside his box, and Leeds capitalised to score their third goal.

How significant was the mistake to the final result?

It restored Leeds’ two-goal cushion and ended Chelsea’s momentum after their earlier goal.

Did Chelsea create enough chances to challenge Leeds?

They improved after halftime but struggled for extended periods against Leeds’ pressing.

What does the defeat mean for Chelsea’s league position?

They remain in the top four but fall further behind the leaders.

Robert Sánchez — 4

Made several routine saves but lacked authority at key moments, particularly on Leeds’ first goal. His distribution was less consistent than usual.

Takeaway: A difficult evening in which his interventions offered limited relief.

Trevoh Chalobah — 5

Lost track of movement during the early corner that led to Bijol’s opener, but settled shortly afterward and adapted when shifted centrally after halftime.

Takeaway: Mixed performance shaped by an unsettled defensive structure.

Tosin Adarabioyo — 3

Struggled to maintain composure under Leeds’ pressure and was directly responsible for the third goal after losing possession inside his own box.

Takeaway: A costly error overshadowed an otherwise steady first-half showing.

Benoît Badiashile — 3

Found it difficult to play through the press and was replaced at halftime after an uncertain opening 45 minutes.

Takeaway: Never established rhythm in possession or in duels.

Marc Cucurella — 5

Advanced well at times and contributed to Neto’s goal by driving play forward, though Leeds’ transitions caused problems behind him.

Takeaway: One of Chelsea’s more proactive outlets despite defensive strain.

Enzo Fernández — 4

Lost the ball in the buildup to Leeds’ second goal and never fully controlled the midfield tempo.

Takeaway: An uncharacteristically loose display in tight spaces.

Andrey Santos — 5

Offered energy in midfield and tracked runners well but found it difficult to slow Leeds’ counterattacks.

Takeaway: Worked hard without being able to shift the momentum.

Estevão — 4

Carried the ball with intent but made several rash decisions, including a late challenge that drew a booking.

Takeaway: Showed flashes of talent but lacked composure against a physical opponent.

João Pedro — 5

Made smart runs and linked play in moments but faded for long stretches and struggled to influence the final third.

Takeaway: Needed more consistent involvement to affect the match.

Jamie Gittens — 6

Ineffective early on but delivered a precise cross for Neto’s goal and improved with more direct running after the interval.

Takeaway: Rebounded well after a slow start.

Liam Delap — 5

Held the ball effectively on a few occasions but found chances limited against Leeds’ central pairing.

Takeaway: Competed strongly without creating decisive moments.

Pedro Neto (46') — 6

Made an immediate impact with a controlled finish at the back post.

Takeaway: Provided the spark Chelsea needed, though the comeback faded quickly.

Malo Gusto (46') — 4

Offered width but struggled in physical duels and did not significantly alter the match pattern.

Takeaway: Could not shift the defensive balance after coming on.

Alejandro Garnacho (61') — 5

Carried the ball well on the left and created one promising opening for Palmer.

Takeaway: Positive energy but limited time to influence the result.

Cole Palmer (61') — 5

Returned from injury and came close with one effort but lacked sharpness in key moments.

Takeaway: Useful minutes ahead of a busier schedule.

The defeat highlighted the fine margins Premier League defenders face when operating under high pressure. Tosin Adarabioyo’s mistake illustrated how a single error can quickly alter a match’s direction, particularly for teams relying on controlled buildup play. With the Leeds vs Chelsea result widening the gap in the title race, Chelsea now enter a decisive run of fixtures requiring greater defensive precision. The focus will be on reducing errors in key areas to protect their top-four standing.

👋👋 Coming up on the site: our look ahead at Simon Jordan’s planned return to watch Crystal Palace after a 15-year absence, examining why the former owner is expected back in the stands and what it could mean for the club. 👉 Read the preview here. 👈

Milwaukee’s assessment of Giannis Antetokounmpo’s long-term plans affects fans, team strategy and the wider NBA market.

Giannis Antetokounmpo and the Milwaukee Bucks are holding ongoing discussions about his future with the team as the Feb. 5 trade deadline approaches.

The talks, confirmed by multiple national outlets, come as Milwaukee falls below early-season expectations and the two-time NBA MVP nears eligibility for a long-term extension in 2026.

The conversations follow a stretch in which the Bucks have slipped outside the Eastern Conference’s top eight, raising questions about the direction of a roster built to compete immediately under general manager Jon Horst and head coach Doc Rivers.

The situation matters for Milwaukee supporters and the broader league because Antetokounmpo remains one of the NBA’s most influential players, averaging more than 30 points per game this season.

His decisions typically shape the competitive balance of the Eastern Conference and influence how teams position themselves with cap space and draft assets.

Any uncertainty around his future changes how the Bucks approach roster moves and affects teams monitoring potential trade or free-agency opportunities.

Milwaukee opened the season with expectations of contending in the East but has struggled to maintain consistency, including an extended losing run that dropped the team below .500.

Publicly available NBA data shows the Bucks performing far better with Antetokounmpo on the court than off, underscoring the team’s reliance on his production.

Recent injuries, including a groin issue that sidelined him for several games, further exposed depth concerns. These factors have increased the urgency surrounding the front office’s talks with Antetokounmpo’s representatives.

Takeaway: Milwaukee’s uneven early-season results have accelerated internal discussions about long-term planning.

Antetokounmpo becomes eligible for a four-year maximum extension on Oct. 1, 2026 under NBA collective bargaining rules, a contract that could exceed $270 million based on current projections.

Players of his stature historically make decisions well in advance, allowing teams to adjust roster construction and manage the salary cap.

Past examples include Stephen Curry’s and Nikola Jokić’s early extensions, which provided clarity for their franchises.

The Bucks now face similar timing pressures as they evaluate whether to build further around Antetokounmpo or consider alternative pathways should he signal uncertainty.

Takeaway: Contract timelines place meaningful pressure on Milwaukee to gain clarity well before 2026.

Public reporting indicates that Antetokounmpo evaluated outside options last offseason, including exploratory interest in the New York Knicks.

While no active negotiations have been confirmed, the NBA’s history shows that star players drive robust trade markets when uncertainty emerges.

Teams with flexible cap sheets, deep draft capital, or younger cores—similar to recent trade frameworks for players like Kevin Durant and Damian Lillard—would likely examine potential packages.

Milwaukee retains control under league rules, but outside interest is expected to intensify if the team’s record does not improve.

Takeaway: The NBA landscape suggests a strong market would form quickly if Antetokounmpo becomes available.

League tracking data shows Antetokounmpo averaging more than 30 points, 10 rebounds and six assists on high efficiency, placing him among this season’s statistical leaders.

Milwaukee’s offensive rating rises significantly when he is on the floor, a trend consistent with prior seasons in which he has been central to the Bucks’ identity.

His durability over the past decade—aside from occasional injuries—has helped Milwaukee remain a perennial playoff team, culminating in the 2021 championship. His current output reinforces why his status remains a major storyline across the league.

Takeaway: Antetokounmpo’s performance continues to rank among the league’s most impactful, shaping Milwaukee’s competitive ceiling.

A significant roster decision involving Antetokounmpo would alter playoff projections in the East, where teams such as Boston, New York and Philadelphia are already tightly clustered in the standings. Player movement among top-tier stars has historically shifted conference power, as seen with Durant’s 2022 move to Phoenix and Kawhi Leonard’s 2018 arrival in Toronto. Milwaukee’s direction will influence how rivals allocate resources and approach the trade deadline, particularly those seeking to close competitive gaps.

Takeaway: Any change in Antetokounmpo’s situation will influence how Eastern Conference teams plan for the postseason.

Is Giannis Antetokounmpo eligible for an extension now?

He becomes eligible for his next maximum extension on Oct. 1, 2026 under NBA contract rules.

Are the Bucks considering a trade?

No trade plans have been announced, but league reporting indicates conversations are ongoing about his long-term fit.

Why is the team’s record important to these talks?

Performance influences roster strategy, contract decisions and a player’s assessment of competitive prospects.

Would other teams pursue him if available?

Yes. Teams with cap flexibility and assets typically engage when a star’s situation becomes uncertain, consistent with recent NBA trade markets.

Has he publicly committed to staying?

Antetokounmpo has broadly expressed loyalty to Milwaukee but has also stated he prioritizes competing for championships.

Giannis Antetokounmpo’s ongoing dialogue with the Milwaukee Bucks matters across the NBA because it involves one of the league’s most influential players and a franchise assessing its competitive direction.

The outcome affects Milwaukee fans, the team’s roster planning, and the broader Eastern Conference landscape. With the trade deadline nearing and contract timelines approaching, the core issue is whether the Bucks can chart a path that aligns with Antetokounmpo’s long-term goals. His future with the Bucks remains a central storyline shaping the league’s competitive balance.