Public disagreements among House Republicans are affecting coordination on legislative scheduling and party strategy.

House Speaker Mike Johnson has called on Republican lawmakers to raise concerns within the conference rather than through public statements or social media, following a recent increase in intra-party criticism. The appeal comes as the House faces a crowded legislative calendar and operates with one of the narrowest majorities in modern congressional history.

The development is significant because visible divisions can limit leadership’s ability to control the floor, negotiate with the Senate, and prepare for policy deadlines. With several competitive districts up for election in 2026 and more retirements than usual for a majority party, internal cohesion has become a central factor in how effectively the House can advance its legislative agenda.

Johnson’s remarks reflect a broader trend in which disagreements that once played out in private conference meetings increasingly emerge in public venues. Such disputes can undermine leadership’s authority under House rules, which rely heavily on majority-party unity for structuring debate and limiting procedural delays. Analysts note that public rifts complicate the whip count process and weaken the party’s negotiating posture across chambers.

The Republican majority holds only a small advantage, making internal cooperation essential for passing party-line legislation. Historically, narrow majorities—as in 2001, 2011, and 2023—experienced heightened internal pressure because just a few defections can block procedural motions. This environment has pushed some lawmakers to use public messaging to influence negotiations, a tactic that becomes more common when committee priorities or regional interests diverge.

Takeaway: A slim majority gives individual members greater leverage, increasing visible friction.

Several recent initiatives have moved forward through discharge petitions, a procedure governed by House Rule XV allowing 218 members to compel a floor vote. While rarely successful, notable past examples include the 2015 petition to revive the Export-Import Bank and earlier bipartisan efforts on campaign finance. Their renewed use signals dissatisfaction with leadership’s gatekeeping role over the floor schedule, especially when bipartisan coalitions form around issues stalled in committee.

Takeaway: The rise in discharge petitions indicates pressure on leadership-controlled processes.

Republicans face a challenging 2026 midterm environment shaped by competitive suburban districts, demographic shifts, and several announced retirements. Historically, majority parties entering midterms with numerous open seats—such as in 1994 and 2018—have encountered greater difficulty retaining control. Members concerned about district-level dynamics are increasingly vocal about the need for legislative messaging that supports economic, fiscal, and national security priorities.

Takeaway: Political uncertainty is intensifying member expectations for strategic clarity.

As committees advance unrelated policy initiatives, disagreements over timing and jurisdiction have become more visible. Recent debates over labor policy, appropriations sequencing, and national security authorizations have highlighted how fragmented priorities strain coordination between leadership offices and committee chairs. Under House rules, committees provide the primary venue for drafting legislation, but leadership must still align competing calendars to maintain momentum.

Takeaway: Differing committee priorities increase the difficulty of maintaining a unified legislative strategy.

Why is Speaker Johnson asking Republicans to keep disputes private?

Because public disagreements complicate internal vote counting, weaken negotiating leverage, and disrupt leadership’s control of the legislative schedule.

What is a discharge petition?

A House mechanism under Rule XV that allows 218 members to bypass leadership and force a vote on a bill.

How does a narrow majority affect party discipline?

With such slim margins, a small number of dissenting members can halt or reshape legislation, increasing internal leverage and tension.

Are these disputes unusual?

Periods of narrow control—under either party—typically see more public disagreements because individual members have greater influence.

Speaker Johnson’s call for private dispute resolution reflects rising concern about the House’s ability to function smoothly under a narrow majority. Public disagreements influence everything from scheduling to committee workflow and bipartisan negotiations. As the 2026 elections approach, the effectiveness of Speaker Johnson in maintaining internal cohesion will help shape legislative output, institutional stability, and the majority party’s strategy for the next Congress.

Escalated strikes on Ukrainian infrastructure affect civilian services and shape ongoing international diplomacy.

Russian forces launched a broad wave of drone and missile strikes across Ukraine overnight, according to Ukrainian authorities, damaging energy and transport facilities in multiple regions. Emergency officials reported injuries and infrastructure disruptions in central and western areas as crews worked to restore essential services.

The attack occurred as U.S. and Ukrainian representatives continue discussions on a potential long-term security framework for Ukraine. The timing underscores how active diplomacy and intensified military operations frequently overlap in the nearly four-year conflict, raising concerns for energy resilience, civilian protection and regional stability.

Ukrainian officials described widespread drone and missile activity across several oblasts, consistent with earlier Russian campaigns targeting power facilities during winter months. Since late 2022, Russia has repeatedly focused on substations, grid nodes and transport hubs, aiming to increase pressure during periods of high energy demand.

Military analysts note that such operations often coincide with political or diplomatic junctures, echoing patterns seen during previous ceasefire discussions or international mediation efforts. Similar escalations accompanied talks in 2022 and 2023, when infrastructure attacks increased before major negotiation rounds.

The latest strikes reflect the long-observed link between battlefield pressure and diplomatic activity.

Ukraine’s transmission network—managed by the state operator Ukrenergo—has endured cumulative damage over several winters. Grid infrastructure, which includes substations and high-voltage connectors, is geographically dispersed but operationally interdependent, leaving the system vulnerable to cascading outages when key nodes are hit.

International agencies such as the International Energy Agency have previously warned that repeated winter strikes risk long repair cycles, heightened repair costs and reduced industrial output. Even when air defenses intercept incoming weapons, falling debris can damage distribution infrastructure and delay restoration.

Ukraine’s interconnected power network remains susceptible to winter disruptions that carry long-term operational consequences.

U.S. and Ukrainian officials have referenced ongoing meetings focused on outlining the components of a future security arrangement for Ukraine. Public statements suggest discussions include military assistance frameworks, monitoring roles and economic recovery mechanisms—elements consistent with prior multinational support initiatives dating back to 2022.

Any durable outcome would require engagement from all parties to the conflict. Previous negotiation attempts, including those facilitated by Turkey and the United Nations, highlight the challenge of securing verifiable commitments while active hostilities continue. Analysts note that absent Russian participation in structured talks, advanced proposals remain preliminary.

Current negotiations address long-term security principles but cannot progress without broader participation.

Russian officials have reported Ukrainian drone activity targeting industrial areas, echoing incidents that have affected refineries and logistics sites across several Russian regions. These reports align with Kyiv’s stated objective of limiting Russia’s fuel production capacity, a strategy that has shaped cross-border drone operations since 2023.

International bodies, including the European Union, have previously flagged risks from expanding drone ranges, such as potential threats to energy corridors, critical infrastructure and commercial transport routes. Increased cross-border activity also complicates airspace safety assessments for civilian aviation authorities.

Cross-border drone use adds broader regional risks beyond direct military targets.

Ukraine could face waves of 2,000 drones as Russia ramps up mass production

Local Ukrainian authorities have reported power outages, heating interruptions and transport disruptions following major attacks in past winters. Municipal planning has since been reinforced with backup power units, additional shelters and energy-saving protocols, supported in part by assistance programs from the European Commission and other international partners.

Despite improved contingency measures, sustained strikes can slow repairs and reduce access to essential services in heavily affected regions. Humanitarian organisations have warned that extended gaps in heating or electricity can increase health and safety risks, particularly for older residents and rural communities.

Civilian infrastructure remains highly exposed, and prolonged disruptions challenge local emergency capacity.

What was the focus of the latest Russian strikes?

Ukrainian officials reported broad attacks on energy and transport infrastructure across several regions.

How many regions were affected?

Authorities confirmed impacts across central and western Ukraine, though assessments are ongoing.

Are these strikes linked to diplomatic talks?

There is no confirmed causal link, but escalations have historically coincided with periods of active diplomacy.

Why are energy facilities frequently targeted?

Power assets are essential for civilian and industrial resilience, and they remain vulnerable during winter months.

How do cross-border drone incidents affect the wider region?

Expanded ranges raise concerns for energy corridors, logistics routes and aviation safety near the conflict zone.

The escalation of Russia drone and missile attacks demonstrates how Ukraine’s civilian infrastructure remains at risk while diplomatic discussions continue abroad. Energy networks, transport systems and emergency services face renewed pressure as winter conditions intensify operational challenges. International partners are monitoring both the humanitarian impact and the implications for regional stability. The coming period will test whether negotiations can advance amid sustained military activity.

Former DEA agent Paul Campo and associate Robert Sensi are charged in New York with conspiring to launder millions for the CJNG cartel and discussing potential access to military-grade weapons. Both men have pleaded not guilty and remain detained as federal proceedings unfold, intensifying scrutiny over law-enforcement integrity.

Former federal agent Paul Campo was charged in New York on Friday in a sweeping conspiracy case that prosecutors say reveals how a onetime DEA insider allegedly agreed to help what he believed was a representative of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG).

The core search-intent question—why was Campo charged?—is answered plainly in the indictment: prosecutors accuse him and 75-year-old associate Robert Sensi of laundering millions in purported cartel proceeds, facilitating cash-to-crypto conversions and discussing routes to obtain military-grade firearms and explosives.

Campo, 61, who retired in 2016 after a 25-year DEA career, was arrested during a controlled undercover operation involving a government informant posing as a CJNG emissary.

Both defendants pleaded not guilty and were ordered detained without bail, a decision shaped by the severity of the narcoterrorism and money-laundering conspiracy counts now facing them.

The emotional stakes are equally stark: a decorated former agent standing accused of agreeing to assist a cartel that U.S. officials say has fueled violence on both sides of the border. With electronic recordings, surveillance evidence and financial tracking at the heart of the government’s case, this prosecution is poised to become one of the most consequential federal corruption cases of the year.

The indictment alleges that Campo and Sensi entered a year-long series of meetings with a confidential informant who claimed to represent CJNG. During these meetings, prosecutors say the defendants agreed to launder around $12 million in supposed drug proceeds and converted approximately $750,000 into cryptocurrency under the belief the funds belonged to the cartel.

According to court filings, the men also provided a payment tied to what they thought would be the sale of 220 kilograms of cocaine in the U.S., expecting a financial return. Discussions reportedly widened to potential access to AR-15-type rifles, M4 carbines, grenade launchers, drones and rocket-propelled grenades.

Campo allegedly referenced his DEA experience repeatedly, describing himself as a potential “strategist” for the cartel’s operations. Prosecutors say evidence includes hours of recorded conversations, emails, surveillance images and cellphone location data.

Both defendants remain in federal custody after a magistrate judge rejected defense efforts to secure release pending trial.

At its core, this is a federal conspiracy case, involving counts linked to narcoterrorism, terrorism, narcotics distribution and money laundering. In the federal system, prosecutors do not need to show that a criminal act was completed—only that:

An agreement existed to commit a federal offence.

The defendants knowingly participated in that agreement.

An overt act took place, such as a meeting, payment, or recorded communication.

Courts typically focus on documentary evidence, recorded conversations, financial transactions and surveillance data. The government must prove each element beyond a reasonable doubt, and each conspiracy count carries serious potential penalties.

Procedurally, the case will move through discovery, evidentiary hearings, pre-trial motions and ultimately trial unless resolved earlier through legal challenges or negotiations.

Campo faces federal conspiracy counts with significant statutory penalties. No outcome can be predicted, but similar narcoterrorism-related charges have historically carried long sentences upon conviction.

The indictment lists four conspiracy counts: narcoterrorism, terrorism, narcotics distribution and money laundering. These counts relate to alleged agreements and overt actions rather than completed transactions.

Court documents indicate that discussions about weapons occurred within a controlled undercover operation. The legal issue is the alleged agreement and actions taken toward that agreement—not the ultimate delivery of weapons.

Because CJNG was designated a foreign terrorist organisation earlier this year, prosecutors may apply terrorism-related statutes that expand jurisdiction, increase penalties and allow broader investigative tools.

Complex conspiracy cases routinely take many months before trial due to voluminous discovery, digital-evidence review and procedural motions.

This case illustrates how federal money-laundering stings and conspiracy charges operate. U.S. law permits charges even when funds come from government sources and when the alleged criminal plan exists largely in recorded conversations. What matters legally is the defendant’s intent and participation in the agreement.

It also shows why law-enforcement misconduct cases have outsized public impact. When a former agent is charged with aiding a cartel, the focus shifts to internal oversight, training, and mechanisms designed to prevent insider exploitation of government expertise.

Additionally, the case highlights how terrorism designations reshape legal frameworks, expanding the tools prosecutors can use to respond to threats involving transnational criminal groups.

The court could find legal deficiencies in certain counts or limit key pieces of evidence through pre-trial motions. In rare cases, charges may be narrowed or dismissed if procedural requirements are not met.

If the case proceeds to trial with the government’s evidence admitted in full, defendants could face convictions on multiple federal conspiracy counts, each with substantial statutory penalties, including terrorism-related enhancements.

Most federal conspiracy cases progress through extensive discovery, motion practice, evidentiary hearings and ultimately a jury trial unless the parties seek a negotiated resolution.

Yes. The indictment lists only the two defendants. No additional defendants have been publicly named.

Health concerns may influence detention arguments but do not alter the charges themselves. Courts weigh medical issues when evaluating risk, not when assessing the underlying allegations.

U.S. media reports note past misconduct cases within the DEA, and agency leadership has acknowledged institutional failures. However, each federal case is adjudicated strictly on its own facts.

Upcoming procedural steps will likely include discovery deadlines and pre-trial motions challenging aspects of the indictment or evidence.

The Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) is one of Mexico’s most powerful and rapidly expanding criminal organisations, known for its aggressive tactics, global trafficking networks, and advanced military-style operations. Emerging in the early 2010s from a faction of the Sinaloa Cartel, CJNG quickly gained influence by combining rapid territorial expansion with sophisticated financial structures that move narcotics, weapons, and illicit funds across multiple continents.

U.S. and Mexican authorities describe CJNG as a vertically integrated organisation capable of producing and transporting synthetic drugs, including fentanyl and methamphetamine, at scale. Its structure blends hierarchical leadership with semi-autonomous regional cells, allowing it to adapt quickly to law-enforcement pressure.

The cartel’s public messaging—often through videos displaying heavily armed groups—serves both intimidation and recruitment functions. In 2025, the United States formally designated CJNG a foreign terrorist organisation, reflecting concerns over violence, corruption, and cross-border criminal activity. Despite sustained enforcement efforts, CJNG remains a dominant force in the Western Hemisphere’s criminal landscape.

Campo and Sensi’s indictment confronts the justice system with a rare and deeply consequential allegation: that a former DEA agent and a longtime associate entered into an agreement they believed would support one of the most dangerous criminal organisations in the hemisphere.

Both men deny the allegations and remain detained as federal prosecutors prepare to present extensive surveillance and financial evidence. The next stage will determine how much of that evidence reaches a jury—and how this case shapes the ongoing national conversation about law-enforcement accountability and cartel-related prosecutions.

Jeremy O. Harris was arrested at Naha Airport after Japanese customs officials allegedly found 0.78 grams of MDMA in his bag. Prosecutors in Okinawa are now reviewing the case under Japan’s strict drug-import laws, which allow weeks of pre-indictment detention. Here is the latest on the legal process and what it means.

Tony-nominated playwright and actor Jeremy O. Harris is under criminal investigation in Japan after customs authorities arrested him on suspicion of importing the drug MDMA into Okinawa. The arrest — confirmed by officials at Naha Airport — immediately prompted the global search-intent question now dominating coverage: why was Harris arrested, and what legal exposure does he face under Japan’s high-control narcotics regime?

Harris, 36, had travelled from London and connected through Taiwan before landing in Naha for what customs officials described as a sightseeing visit. Instead, airport officers reportedly discovered 0.78 grams of crystalised MDMA inside a container in his tote bag. He was detained on November 16 and transferred to the Tomishiro police, who later submitted a criminal complaint to the Naha District Prosecutors’ Office.

Japan’s criminal procedure places exceptional weight on the investigative stage: suspects can be held for up to 23 days without indictment, and pretrial detention may extend further depending on procedural developments. For Harris — a globally recognised figure known for pushing boundaries in theatre and television — the arrest presents a deeply consequential clash with one of the world’s strictest drug-control systems, where even small quantities can lead to serious charges.

Japanese customs officials say the alleged MDMA was discovered during routine baggage screening shortly after Harris arrived in Okinawa. Authorities confirmed that no additional drugs were found in his possessions.

Harris was taken into custody immediately and has remained under the oversight of investigators while prosecutors assess whether the statutory criteria for indictment are satisfied. His representatives have issued no public comment, and Japanese authorities are prohibited from disclosing whether he made statements during questioning.

The criminal complaint is now in the hands of the Naha District Prosecutors’ Office, which has broad discretion to charge, dismiss, or request further investigation.

This case turns on Japan’s customs and narcotics-import laws, which establish strict liability for bringing controlled substances into the country. MDMA is classified as an illegal stimulant, and its importation is treated as a smuggling offence irrespective of quantity or personal-use intent.

Prosecutors typically examine:

whether the substance is prohibited under the Narcotics and Psychotropics Control Act

whether the traveller knowingly brought the substance across Japan’s border

physical and circumstantial evidence such as packaging, placement, and travel pattern

customs documentation and officer testimony

Japan’s justice system emphasises pre-indictment investigation. Authorities use this period to verify the chemical analysis, establish importation elements, and determine whether circumstances satisfy statutory thresholds. If indicted, cases proceed to a bench trial, where penalties for drug importation may include a multi-year prison term upon conviction.

A custodial sentence is one potential outcome in drug-import cases under Japanese law. Whether that becomes relevant depends entirely on prosecutors’ charging decision and the court’s assessment if the case proceeds to trial.

Authorities are evaluating potential violations of customs and narcotics statutes related to importing a controlled substance. Prosecutors have not yet confirmed whether a formal indictment will be issued.

Yes. Prosecutors can decline to indict if the evidence does not meet statutory requirements. This review is procedural and does not reflect on public perception or celebrity status.

The pre-indictment phase may last up to 23 days from arrest, and additional steps follow if charges are filed. Trials in Japan often extend over months as courts evaluate evidence and allocate hearing schedules.

Harris’ case underscores how drug laws vary dramatically across jurisdictions. In Japan, even very small amounts of a prohibited substance discovered at the border are automatically treated as importation allegations, not simple possession. Additionally, Japan’s pre-indictment detention rules allow extended custody while investigators consolidate the evidentiary record.

For foreign travellers, the broader legal principle is clear: customs violations involving controlled substances trigger immediate criminal scrutiny, and procedural norms may differ sharply from those in their home countries.

Best-case procedural scenario:

Prosecutors decide there is insufficient basis for indictment, and Harris is released without formal charges.

Worst-case procedural scenario:

He is indicted for importing a controlled substance, the case proceeds to trial, and — if convicted — Japanese law allows multi-year imprisonment.

Most common procedural pathway in similar cases:

A full evidentiary review during detention, followed by a prosecutorial charging decision and, if indicted, a structured court process involving hearings and judge-led fact-finding.

Can a foreign national be detained for the full 23-day period?

Yes. Japan applies its detention rules uniformly, and the 23-day window is frequently used in customs-related narcotics cases.

Does the tiny quantity affect the classification?

While quantity may influence potential sentencing categories, it does not remove the legal basis for an importation allegation.

Can bail be requested before indictment?

No. Bail in Japan generally becomes available only after formal charges are filed.

Does celebrity status change how the law is applied?

No. Japanese criminal procedure is applied without regard to personal profile or profession.

Jeremy O. Harris now faces the early but decisive stages of Japan’s drug-import legal process, one defined by strict statutory standards and extended pre-charge review. Prosecutors will determine whether the evidence supports indictment — a decision that will shape every subsequent step of the case. For now, the proceedings highlight the heightened risks international travellers face under Japan’s narcotics laws and the global scrutiny that follows when a prominent artist becomes entangled in them.

Secret Lives of Mormon Wives star Chase McWhorter has confirmed he was arrested on 4 July in Utah for DUI and alleged drug possession. His new TikTok apology lays out what happened that night and underscores the serious charges and court process now ahead of him.

Chase McWhorter, the 30-year-old reality figure from The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives, has finally addressed the question driving national searches: what happened during his DUI and alleged drug-use arrest, and what does it mean for him now?

In a 4 December TikTok statement, McWhorter confirmed that reports about his 4 July traffic stop in Utah are accurate, admitting he drove after ingesting substances he “shouldn’t have” and describing the decision as “selfish” and “dangerous.”

Police documents referenced in U.S. reporting detail that the stop occurred after officers observed erratic lane movement and later claimed to find suspected narcotics inside the vehicle. Additional filings indicate he was charged with DUI, possession of a controlled substance and driving on a suspended licence. A missed September court appearance briefly triggered an arrest warrant before his attorney entered a not guilty plea and resolved the issue.

For a public personality already navigating post-divorce scrutiny, shifting co-parenting dynamics and reality-TV attention, the arrest now carries real legal consequences. His apology—raw, direct and at times emotional—has reignited interest in how this case will move through Utah’s criminal system and what it could mean for his future.

Police reports say McWhorter was pulled over on 4 July after officers received information about a white Tesla swerving in its lane. Officers stated that he showed signs of impairment and later claimed they found a substance that tested positive for controlled drugs. Toxicology testing referenced in public filings reportedly showed the presence of multiple substances.

According to court records reported by U.S. outlets, McWhorter was charged with DUI, possession or use of a controlled substance and driving on a suspended or revoked licence. A warrant was issued in September after he allegedly failed to appear for an initial hearing, but it was recalled once counsel filed a not guilty plea on his behalf.

In his TikTok video, McWhorter did not contest the underlying events. Instead, he expressed regret, apologised to his ex-wife Miranda—whom he notified the following day—and acknowledged the personal and legal fallout that continues to unfold.

@dchasemac

McWhorter’s case involves three separate criminal offences:

• Driving under the influence (DUI): Prosecutors must show the defendant operated a vehicle while impaired or over a statutory limit. Courts typically examine officer observations, sobriety testing, toxicology results and video evidence.

• Possession of a controlled substance: The issue is whether a person knowingly possessed or used an unlawful substance. Evidence usually includes where the material was found, lab confirmation and whether the search complied with constitutional requirements.

• Driving on a suspended licence: This focuses on whether the licence was valid and whether the driver knew of the suspension.

Cases like this move through arraignment, discovery, pre-trial negotiations and—if necessary—trial. Potential penalties range from fines, education or treatment programmes and probation to licence restrictions and, in some instances, short custodial terms.

Jail is legally possible for DUI, drug-possession and licence-related charges. Whether custody is imposed depends on statutory ranges, prior record and judicial discretion.

Public court filings indicate three charges: DUI, possession or use of a controlled substance and driving on a suspended licence. Each carries its own elements and potential penalties.

Reports say his attorney has filed a not guilty plea, a standard early procedural step that preserves all legal defences while evidence is reviewed.

He admitted driving after ingesting substances, called the act “dangerous,” apologised to his ex-wife and followers and acknowledged the consequences he is now facing.

Because McWhorter’s personal life and public persona are tied to family dynamics, faith and high-profile relationship breakdowns, the arrest has broader resonance—illustrating how quickly a real-world criminal case can reshape a public figure’s trajectory.

This case mirrors a common reality: even a short drive while impaired can set off parallel criminal proceedings, insurance consequences, licence suspensions and long-term record considerations. DUI laws are designed to intervene before harm occurs. A driver does not need to cause an accident to face serious charges.

Drug-possession allegations often arise from what officers say they observe or find during a traffic stop. Even minimal quantities can carry criminal exposure, especially when paired with impairment-related accusations.

For parents, a single incident can later appear in family-law disputes or professional licensing reviews. The broader message is that the legal system treats these charges the same way, regardless of a person’s public profile.

A negotiated resolution involving probation, fines, mandatory education or treatment and a defined licence restriction period, with no active jail term.

If the case went to trial and resulted in convictions across multiple counts, the court could impose a combination of jail time, longer licence suspension, higher fines and monitoring conditions.

Many first-time cases resolve through plea agreements outlining treatment, supervision and fines, avoiding a full trial. Specific outcomes depend on statutory rules and the evidence exchanged between both sides.

Does a public apology matter legally?

Not directly. Courts rely on admissible evidence and statutory criteria, though counsel may reference remorse during sentencing discussions.

Can this affect his work or sponsorships?

Potentially. Criminal cases can influence brand partnerships and employment decisions, even when penalties are relatively limited.

Is missing a court date a separate issue?

It can be. Missed hearings often trigger warrants until the defendant or counsel resolves the non-appearance with the court.

Are DUI laws the same everywhere?

No. Definitions, penalties and diversion options vary by state, meaning similar conduct can produce different legal outcomes depending on jurisdiction.

Chase McWhorter’s confirmation of his 4 July arrest anchors the case firmly within Utah’s criminal process: DUI, possession and licence-status charges, followed by a not guilty plea and ongoing court supervision. His public apology signals personal accountability, but it does not affect the legal pathway ahead.

The coming months will centre on court dates, negotiations and statutory requirements—an unmistakable reminder of how swiftly an impaired-driving incident becomes a full legal crisis with enduring personal repercussions.

👉 Related: Zachery Ty Bryan’s Fiancée Hit with No Contact Order After Dramatic DUI and Endangerment Arrest 👈

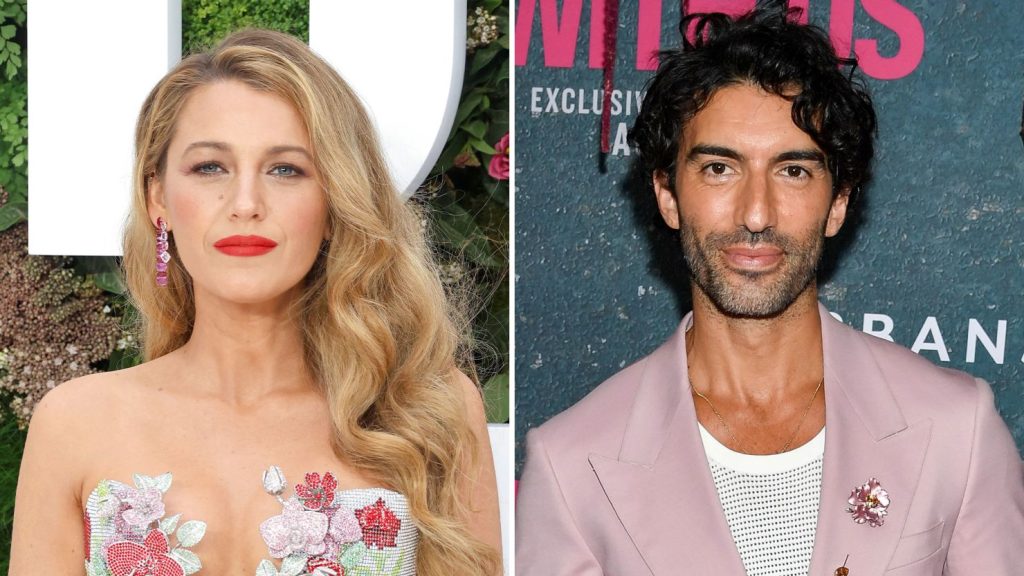

New court filings show Justin Baldoni confirmed in an October 2025 deposition that he told Blake Lively he is circumcised during a 2022 visit to her New York home. The disclosure is now a central issue in Lively’s harassment lawsuit as both sides fight over whether the case proceeds to a March 2026 jury trial.

Justin Baldoni’s own sworn testimony has pushed his legal battle with Blake Lively into an even sharper spotlight, after he confirmed in an October 2025 deposition that he told the actress he is circumcised during a December 2022 visit to her New York City apartment.

Lively, who was pregnant at the time, says the interaction deeply unsettled her and forms part of her broader harassment case linked to their work on It Ends With Us.

The deposition describes a crowded living room where Ryan Reynolds, nannies, assistants and household staff moved in and out as the two actors sat on a couch discussing several topics—including, reportedly, circumcision. Baldoni insists the conversation was neither initiated by him nor sexual; Lively’s lawyers say the remark exemplifies inappropriate professional boundaries and should be evaluated by a jury.

With Baldoni seeking summary judgment and Lively urging the court to deny it, the stakes now centre on a single question: will a federal judge allow this case to reach a jury in March 2026, or will the lawsuit end before trial? The answer will determine the next phase of one of Hollywood’s most closely watched workplace disputes.

During a December 2022 visit to Lively’s Manhattan home, the topic of circumcision arose while she and Baldoni were speaking on the couch. In his 2025 deposition, Baldoni acknowledged telling Lively he is circumcised but said she did not “directly” ask him.

He described the environment as bustling, with Ryan Reynolds moving in and out of the room, two nannies present, assistants walking through and general household activity unfolding as they spoke. When asked if he typically discusses his genitalia with colleagues, Baldoni said he does not.

Lively’s amended complaint states she was one of the “women or two” Baldoni “one million percent” made uncomfortable, and she argues the genitalia remark supports her claims. Baldoni denies wrongdoing and has asked the court to dismiss the case. Lively’s legal team filed a Dec. 4 opposition urging the judge to allow a full trial.

This is a civil sexual harassment and retaliation lawsuit, not a criminal case.

To determine whether it proceeds to trial, the court examines:

whether the conduct was unwelcome

whether context and content could contribute to a hostile environment

whether the behaviour was severe or pervasive under federal or state standards

whether any alleged retaliation followed complaints

Evidence typically includes sworn depositions, messages, emails, internal reports, witness accounts and production-related documentation.

A summary-judgment motion—like the one Baldoni filed—asks the judge to rule without a trial if no reasonable jury could find for the plaintiff. If factual disputes remain, the law requires the case to proceed toward trial.

No. This is a civil lawsuit. There are no criminal charges and no potential imprisonment.

Because it forms a concrete, undisputed event the court must slot into the broader context of Lively’s claims about inappropriate workplace behaviour and discomfort arising from interactions with Baldoni.

Yes. If the judge agrees that no material facts justify a trial, summary judgment would end the lawsuit. If not, proceedings move toward March 2026.

The parties begin trial preparation, which may involve additional discovery, pre-trial motions, witness preparation and possible settlement talks.

Not alone. Courts consider patterns, context and cumulative effect when assessing harassment claims.

This case demonstrates how seemingly informal conversations can become legally significant when they occur within professional or workplace-adjacent settings. Many employees may not realise that comments about bodies, sex or personal boundaries—even in mixed company—can be evaluated under harassment law if they make someone uncomfortable and intersect with workplace dynamics.

It also illustrates how depositions shape litigation. Once spoken under oath, an individual’s own words become central evidence and may enter the public record. Summary-judgment motions similarly show how courts act as gatekeepers, ensuring only cases with legitimate factual disputes advance to trial.

Best-case procedural scenario

The judge sides with the moving party on summary judgment—ending the lawsuit (best for Baldoni) or clearing it for trial without further challenge (best for Lively).

Worst-case procedural scenario

A full jury trial proceeds, bringing extensive testimony, public attention and prolonged legal exposure for both sides.

Most common scenario in similar disputes

Summary judgment is denied or partially denied, leading to trial preparation and, often, intensified settlement negotiations before any jury is empanelled.

Will Blake Lively have to testify if the case goes to trial?

In most civil harassment cases, plaintiffs do testify because their experiences are central to the claim.

Can Justin Baldoni speak publicly about the deposition?

Parties can comment publicly unless restricted by protective orders, though lawyers often manage communications.

Could the case settle before March 2026?

Yes. Most civil cases resolve before reaching a jury, though no settlement has been disclosed.

Does this affect the film It Ends With Us?

The lawsuit references events connected to the production, but distribution decisions are separate.

Justin Baldoni’s statement confirming he told Blake Lively he is circumcised—once a private exchange—has now become a pivotal fact before the court. It will help determine whether a federal judge views the case as one requiring a jury’s evaluation or one suitable for dismissal.

The ruling on summary judgment will define the trajectory of a dispute that blends workplace boundaries, celebrity dynamics and modern harassment law. Whether or not the case reaches trial, this moment underscores how a single candid remark can become the fulcrum of a high-stakes legal battle.

The 16-year-old boy has been placed with relatives while federal agents investigate the homicide of Florida teen Anna Kepner aboard a Carnival cruise ship.

The 16-year-old stepbrother of Florida student Anna Kepner is now living with relatives at a confidential location as federal authorities continue examining her death aboard a Caribbean cruise, according to court filings and statements in family court.

Kepner, 18, was found dead under a bed in a shared cabin on the Carnival Horizon during a November voyage from Miami. Her death certificate lists the cause as mechanical asphyxia inflicted by another person, and the case has been ruled a homicide.

The teen’s relocation was arranged by his parents after the ship returned to the United States.

The decision has heightened public interest because the FBI has not yet determined whether the case will be referred to federal or state prosecutors. The investigation touches on maritime jurisdiction, cruise-ship safety procedures, and how courts handle child welfare issues when a minor becomes connected to a homicide inquiry.

Anna was found dead in her cabin on the Carnival Horizon on the morning of Nov. 7 as the ship travelled back to port in Miami.

Court filings show the boy was placed with a relative granted power of attorney, and his whereabouts are known only to his parents and law enforcement. The move was described in court as a precaution intended to reduce potential risk to siblings and stabilize the home environment while the federal investigation continues.

Both parents acknowledged in filings that the teenager is being treated by investigators as a suspect or focal point of inquiry, though no public charging decision has been made. Child-welfare experts say voluntary placements of minors in such scenarios are often used to maintain safety and lower conflict within households during lengthy investigations.

The relocation is a preventative measure while the teen remains under federal scrutiny but faces no formal charges.

The FBI is leading the investigation because the death occurred aboard a cruise vessel operating largely in international waters but returning to a U.S. port. Agents collected evidence upon docking in Miami and reviewed findings with the Miami-Dade Medical Examiner, who confirmed homicide.

Large cruise ships present complex investigative challenges. Authorities typically analyze cabin access records, security video and passenger interviews before determining whether state or federal prosecutors should take the case. The Justice Department has not indicated when a charging decision will be made.

Federal maritime jurisdiction guides the investigation, and prosecutorial authority will depend on how evidence aligns with state and federal law.

The boy’s relocation overlaps with a custody dispute pending in Florida family court. One parent sought emergency custody of another child following Kepner’s death, arguing that the circumstances raised safety concerns. A judge denied that request, concluding the evidence did not demonstrate immediate risk.

Further hearings are scheduled to review longer-term arrangements. Judges generally wait for additional verified information from investigators before modifying parenting plans that affect children unrelated to the incident.

Family court is monitoring the case but has not altered existing custody orders absent confirmed risk.

Kepner, a high-school senior from Titusville, Florida, joined a weeklong Caribbean cruise with family members in early November. Public records indicate she shared a cabin with her 16-year-old stepbrother and a younger sibling. She was discovered dead on the morning of Nov. 7 shortly before the vessel returned to Miami.

Her death certificate states she died from mechanical asphyxia caused by another person, leading authorities to classify the case as homicide. No public evidence has identified a suspect.

Confirmed records show Kepner was killed in the shared cabin, but authorities have released limited details while the investigation continues.

Cases involving juvenile witnesses or potential suspects require specialized procedures, including forensic interviews conducted under strict child-protection standards. Agencies are barred from releasing identifying information that could compromise a minor’s legal rights.

In the Kepner case, filings indicate that psychological assessments of the 16-year-old are ongoing while investigators analyze evidence collected from the ship. These factors, along with maritime jurisdiction, typically extend investigative timelines.

Confidentiality rules and juvenile protections slow the pace of criminal inquiries involving minors.

Is the 16-year-old stepbrother officially a suspect?

Court records describe him as a suspect or focus of inquiry, but no charges have been filed and authorities have not publicly named him.

Has anyone been arrested in the case?

No arrests or charges have been announced.

Who is leading the investigation?

The FBI, with support from the Miami-Dade Medical Examiner and other agencies, has primary jurisdiction because the incident occurred at sea.

What court actions remain pending?

Family-court hearings in Florida will continue later this month to assess custody and compliance issues between the parents.

Has Carnival commented?

Carnival has said it is cooperating with law enforcement but has not released detailed statements during the active investigation.

The homicide of Anna Kepner aboard a cruise ship has prompted a multifaceted review involving federal investigators, state courts and child-welfare officials.

The relocation of the Anna Kepner's stepbrother underscores the precautionary steps families and courts take when a minor becomes part of a homicide investigation but has not been charged. The case highlights the challenges of investigating serious crimes at sea and raises broader questions about cruise-ship safety procedures and juvenile protections. As the FBI continues its work and family-court hearings progress, the central issues remain public safety, accountability and child welfare.

Brooke Mueller has filed a new court motion alleging Charlie Sheen owes more than $15 million in unpaid child support and interest for their twin sons. The filing seeks a court order compelling payment within 30 days, reigniting a decade-long financial dispute.

Charlie Sheen is once again under legal pressure after ex-wife Brooke Mueller filed a detailed enforcement motion alleging he owes more than $15 million in unpaid child support and accumulated interest.

Filed in Los Angeles Superior Court, the petition outlines what Mueller says is a decade-long pattern of partial payments, missed instalments, and mounting arrears tied to the former couple’s 16-year-old twin sons, Bob and Max.

Early media summaries of the filing state that Mueller calculates roughly $8.9 million in unpaid support and more than $6.4 million in interest, bringing the total to about $15.3 million.

She is asking the court to order Sheen, now 60, to pay the full amount within 30 days and to cover $25,000 of her legal fees associated with the motion.

The stakes are significant. Child support arrears function as a form of judgment debt, and once they accumulate, they cannot normally be reduced retroactively.

If a judge confirms the amounts, the court could impose repayment plans, wage garnishment, or other enforcement tools. For Sheen—whose finances have been scrutinised since his exit from Two and a Half Men—the latest claims revive a long-running dispute with real legal and financial consequences.

Charlie Sheen and Brooke Mueller pictured dining with their two young children during an outing years before the current child-support dispute.

Mueller and Sheen divorced in 2011, with earlier court orders requiring Sheen to pay $55,000 per month in support for their sons. According to Mueller’s new filing, Sheen paid in full through June 2011 but began making only partial payments from July onward.

The filing alleges that some years saw no payments at all, while others included sporadic amounts far below the ordered sum. Based on those records, Mueller claims $8.97 million in unpaid support and more than $6.4 million in statutory interest. She is now asking the court to verify the calculations and require repayment within 30 days of a judicial order.

Sheen has not yet responded publicly. The court will now determine hearing schedules, evidence submissions, and next steps in the enforcement process.

This case is a child support enforcement action, not a criminal prosecution. Once a child support instalment becomes due, it is treated as a vested debt—meaning it cannot typically be altered retroactively. If a parent’s ability to pay changes, they must request a modification before future payments come due.

Key legal principles include:

Arrears are enforceable debts. Courts treat them similarly to other forms of judgment debt.

Interest accrues automatically. Many states require statutory interest on unpaid support, often at high annual rates.

Courts examine documentation. Payment history, bank records, and prior orders determine whether arrears exist.

Enforcement tools escalate gradually. Judges often begin with payment plans and wage withholding, reserving stronger measures for persistent non-compliance.

Not at this stage. Jail is rare in the early phases of child support enforcement and typically applies only after a court finds wilful, ongoing refusal to comply with confirmed orders.

She seeks confirmation of approximately $15.3 million in arrears and interest, an order requiring payment within 30 days, and reimbursement of $25,000 in attorney’s fees.

Sheen is accused of making sporadic or partial payments from mid-2011 to 2025. Over time, each missed instalment becomes a separate debt, and statutory interest accumulates, causing totals to grow significantly.

Income changes can justify modifying future support if raised promptly before the court. They generally do not erase historical arrears.

Custody arrangements may influence future support obligations but do not erase past debts already accrued.

This case highlights several universal features of child support law:

Obligations do not automatically adjust when a parent’s circumstances change.

Missed payments can grow into substantial arrears, especially once interest accumulates.

Courts rely heavily on documentation, not memory or informal agreements.

Support is seen as the child’s right, not just a financial dispute between parents.

For any parent, the lesson is clear: if income changes, the only safe route is to seek a formal modification from the court.

Both parties could reconcile payment records, agree on a verified arrears figure, and establish a court-approved repayment plan without extended litigation.

If the court confirms large arrears and orders go unmet, enforcement could escalate to wage garnishment, liens, or—only in extreme cases—contempt proceedings.

Courts usually confirm the arrears, calculate interest, and issue a written enforcement order outlining repayment steps, followed by periodic compliance reviews.

👉🟡 Charlie Sheen Net Worth 2026: From $150 Million Peak to $3 Million Today 🟡👈

(A deep dive into Sheen’s earnings, losses, TV fortune, asset sales, legal costs, and how his net worth transformed over two decades.)

No. Arrears remain collectible for many years and often behave like long-term judgment debt.

Only with court approval, and even then, some categories of arrears—such as those owed to the state—cannot be waived.

Courts consider addiction only when it affects parenting time or earning capacity. It does not forgive arrears owed under prior orders.

The motion concerns alleged non-payment, not a full assessment of Sheen’s current finances. That determination comes later through required disclosures.

Brooke Mueller’s enforcement motion marks a critical moment in a long-running financial dispute with Charlie Sheen. The case now moves into a technical legal phase, where the court will assess historical records, confirm—if applicable—the arrears amount, and determine how repayment should proceed.

The dispute underscores a wider legal truth: child support orders remain enforceable long after they are issued, and interest can turn years of missed payments into substantial liabilities. Whatever happens next, the outcome will hinge on documentation, judicial review, and the best interests of the children at the centre of the case.

A new 2025 interview with designer Oscar G. Lopez claims Jay-Z’s compliment about Rachel Roy’s Met Gala dress helped spark Solange Knowles’ infamous 2014 elevator outburst. The confrontation, caught on hotel security footage, never led to criminal charges but remains one of the most dissected celebrity conflicts of the decade. Here’s the legal meaning behind the resurfaced claim.

On the night of the 2014 Met Gala, a silent elevator at The Standard, High Line in Manhattan captured one of the most viral celebrity moments of the modern era.

As the doors slid shut, Solange Knowles stepped toward her brother-in-law Jay-Z, kicking and swinging as a bodyguard intervened and Beyoncé watched from inches away. The leaked footage — grainy, wordless and instantly iconic — exploded across global media and raised a simple but urgent question: what actually caused the fight, and did the law ever have a role to play?

That question has resurfaced in December 2025 after fashion designer Oscar G. Lopez, who created Rachel Roy’s black lace Met Gala gown, publicly claimed that Jay-Z complimented Roy’s dress earlier in the evening and that Solange viewed the exchange as improper. His account reignites long-running speculation around the emotional context of the confrontation while reviving public interest in why the high-profile altercation never evolved into a criminal case.

Despite the intensity of the footage, no police report was filed, no injuries were documented and no civil complaint ever emerged. For the family, the moment was a private matter resolved internally; for the public, it became a symbol of fame colliding with surveillance culture; and for the law, it remained a closed non-case.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(999x0:1001x2)/beyonce-solange-6-0556f683d54f48709d1c63b76623f2f3.jpg)

A new detail has emerged offering fresh insight into what sparked Jay-Z and Solange Knowles’ now-infamous elevator confrontation.

The incident occurred shortly after the Met Gala afterparty in May 2014. Jay-Z, Beyoncé and Solange entered the hotel elevator alongside a bodyguard. Moments later, Solange advanced toward Jay-Z, appearing to strike him while the bodyguard pressed the emergency stop and attempted to restrain her. The footage leaked days later, reportedly recorded off a monitor by an employee who was subsequently dismissed.

A joint family statement issued soon afterward said the parties had apologised to one another and “moved forward as a united family.” There were no public complaints, no reports of injury and no indication that anyone sought legal intervention. The moment nevertheless dominated cultural conversation, amplified by later artistic references: Beyoncé’s “Flawless” remix nodding to elevator drama and Jay-Z’s admissions of marital infidelity in later music.

Designer Oscar G. Lopez’s 2025 claim — that Jay-Z complimented Rachel Roy’s dress and Solange perceived it as inappropriate — adds context to the emotional backdrop but does not alter the legal history. The fight never entered a courtroom, and the resurfaced explanation does not create new legal exposure.

Fashion designer Oscar G. Lopez, who created Rachel Roy’s 2014 Met Gala gown, has said that Jay-Z complimented Roy’s dress that night — a moment he believes contributed to tension with Solange Knowles.

The central legal question is when a physical altercation becomes a prosecutable assault. In most U.S. jurisdictions, prosecutors typically need:

conduct that meets the statutory definition of an assault or harassment

evidence of injury or risk

a complainant or cooperative witnesses

In this case, none of the participants filed a police report. With no identified injuries, no statements and no complainant, the incident did not meet the threshold for law enforcement involvement. Viral footage alone is rarely enough to prompt prosecutors to launch an unsolicited case, especially where the individuals involved prefer private resolution.

Had a report been made, authorities would have assessed video evidence, witness accounts and any medical information to determine whether the conduct met legal standards for intent, harm or threat. Outcomes in such cases range from diversion programmes to fines or, in more serious matters, probation or short custodial sentences. None of those processes were triggered here.

No. The altercation is more than a decade old, and any statute of limitations for minor assault or harassment has long expired. The 2025 claim does not change that.

Unlikely. Police rarely act on video alone without cooperation from the people involved and without clear evidence of significant harm.

Yes. The footage belonged to the hotel, and the unauthorised leak raised serious privacy concerns. The employee responsible was reportedly terminated, but no public civil or criminal case followed.

No. His account offers potential emotional context, not new evidence of criminal conduct. The absence of a complaint remains decisive.

Because Lopez’s explanation touches on long-running rumours about the relationships and dynamics surrounding that night, renewing public curiosity about an incident the legal system never pursued.

The episode highlights a crucial point in assault law: police involvement is not automatic. Physical contact does not always equal a criminal case. Prosecutors generally need a victim willing to cooperate, evidence of harm and a clear legal basis to proceed.

It also shows how surveillance footage can reshape a narrative instantly. A private disagreement that once would have faded quietly became a cultural landmark when the video leaked — despite the absence of legal consequences.

Most importantly, it demonstrates how family-related disputes often resolve outside formal systems. Prosecutors prioritise cases involving significant injury, ongoing danger or vulnerable victims, not one-off altercations among adults who decline to press charges.

No complaint, no law-enforcement involvement and a private reconciliation, supported by a joint family statement. The matter stayed personal, not legal.

If someone alleged injury or fear and cooperated with police, authorities could investigate, gather statements and potentially bring assault or harassment charges, resulting in court dates, protective orders or fines.

Most low-level disputes between family members or acquaintances end privately when no one files a report. Without cooperation, prosecutors typically decline to proceed.

Was Jay-Z required to press charges?

No. In low-level assault cases, the person involved can choose not to make a statement. Without a cooperative complainant, cases rarely move forward.

Could Beyoncé or hotel staff have triggered a case instead?

They could have reported the incident, but there is no record that they did. Hotels often address leaks internally without involving law enforcement.

Does the 2025 explanation prove motive?

No. It reflects Lopez’s perspective on the events surrounding the evening, not a legal finding. The family’s own statement emphasised reconciliation.

Is this connected to other legal matters involving the family?

No. The elevator incident stands alone and has no formal legal connection to later artistic or personal disclosures.

The 2025 claim sheds new light on interpersonal dynamics but does not reopen a legal matter that never became a case. The 2014 elevator fight remains a cultural moment defined by viral footage and family tension rather than criminal process. Its enduring relevance lies in what it reveals about privacy, surveillance and the limits of the justice system — not in unresolved legal questions.

For readers navigating California’s family-violence statutes, this guide breaks down the key definitions and protections.

👉 What Is Domestic Violence in California? The 2025 Guide to Understanding the Law, Your Rights, and the Real Consequences 👈

A deposition remark by Justin Baldoni has intensified scrutiny of an ongoing workplace-conduct lawsuit involving Blake Lively, affecting industry discussions on set safety and accountability.

Court records released this week detail comments actor-director Justin Baldoni, 41, made about actor Blake Lively, 38, during a 2025 deposition connected to her civil lawsuit alleging harassment and retaliation during the production of It Ends With Us.

The filing describes Baldoni characterizing Lively’s actions as a strategic effort to frame workplace concerns, referring to what he called a “Taylor Swift playbook.” The remark appeared in text messages introduced as part of the discovery process and is now part of the broader evidentiary record.

The disclosure matters because it highlights how off-camera interactions are increasingly evaluated through legal frameworks governing workplace safety in the entertainment sector.

Lively’s claims fall under state and federal anti-harassment standards, and the litigation raises questions about oversight obligations, boundary protocols and the role of personal communications in assessing disputed conduct on film sets.

The case is scheduled for trial in 2026, making the comment relevant to how courts will interpret the dynamics between the two performers.

Justin Baldoni criticized Blake Lively’s conduct on the set of It Ends With Us, alleging she portrayed herself as a victim during production.

The comment emerged from text messages Baldoni sent after a January 2024 production meeting where Lively outlined conditions she said were necessary to ensure a safe working environment.

His deposition confirms he perceived her concerns as part of a broader reputational risk for him and the film. Attorneys for both sides introduced the messages to clarify his state of mind during the escalation of the dispute.

Under U.S. civil-procedure rules, written communications relevant to motive or workplace perception can be admitted to help courts assess whether conduct met legal thresholds for harassment or retaliation.

The remark is relevant because it illustrates Baldoni’s understanding of the conflict, which may influence how a jury interprets intent and workplace context.

Lively filed a complaint in late 2024 alleging that comments and interactions during filming created an unsafe environment and that raising concerns led to retaliation and negative characterizations of her role on set.

She later filed a civil action seeking financial damages for harassment-related violations, emotional distress and lost earnings. Baldoni denied the allegations and previously filed his own claims, though those counterclaims were later dismissed by the court.

Entertainment-industry employment disputes often involve overlapping legal questions, including whether reported conduct constituted protected activity, whether subsequent actions could be considered retaliatory and whether safety protocols were followed.

California and New York, where aspects of the production took place, have strengthened employee protections in recent years, making compliance a central issue in litigation involving creative workplaces.

The lawsuit grew from on-set disagreements into a multifaceted legal case testing evolving workplace-conduct standards.

Filings show Baldoni described Lively as having significant influence due to longstanding professional and personal relationships, including with figures such as Taylor Swift. His attorneys argued the remark reflected his perception of potential reputational harm, while Lively’s team says it demonstrates a pattern of minimizing her workplace concerns by framing them as strategic rather than substantive.

Courts regularly assess whether comments about a complainant’s industry standing or public visibility are relevant to claims of retaliation or credibility attacks. In this case, such references may help the judge determine whether characterizations made about Lively formed part of a defensive posture or an attempt to undermine her workplace assertions.

Mentions of high-profile relationships are legally significant because they relate to influence, motive and perceived leverage.

He called it the “Taylor Swift playbook.”

According to the filings, Lively requested updated safety measures aligned with prevailing entertainment-industry guidelines: regular presence of an intimacy coordinator, closed sets for sensitive scenes, clear boundaries regarding physical contact outside of filming and the prohibition of unscripted intimate improvisation. These practices are widely adopted following industry reforms introduced in the late 2010s.

Such protocols intersect with state workplace-safety requirements designed to prevent harassment and ensure informed consent during performance staging. Whether the production fulfilled those requirements, and whether concerns raised were met with appropriate responses, will be key elements for the court to consider.

The case hinges in part on whether modern intimacy-coordination standards were followed and whether responses to concerns met legal obligations.

As of December 2025, Baldoni’s countersuit has been dismissed, leaving Lively’s claims as the central matter moving toward trial. Baldoni has sought dismissal of the remaining allegations, arguing the conduct described does not meet legal thresholds for harassment, retaliation or damages. Lively’s attorneys argue the case should proceed to a jury because the record includes evidence of boundary disputes, contested communications and alleged reputational harm.

The court will need to determine whether the allegations, supported by documents and testimony, present factual questions appropriate for a jury under employment and civil-rights law. The trial schedule indicates the dispute remains active, with further hearings expected in early 2026.

The primary unresolved question is whether the court will allow a jury to weigh the competing accounts of on-set conduct and workplace response.

What prompted public attention to the remark?

The comment was disclosed through deposition materials included in a publicly filed motion in the ongoing civil case.

Is the lawsuit resolved?

No. Counterclaims have been dismissed, but Lively’s allegations remain active and are expected to proceed unless the court grants dismissal.

Does the remark affect the film’s release?

The film was released in 2024; current litigation affects workplace-conduct assessments, not distribution.

Is Taylor Swift involved in the case?

She is not a party. Her name appears only in relation to messages and references describing perceived industry influence.

The dispute involving Justin Baldoni’s “Taylor Swift playbook” remark underscores broader questions about accountability, workplace safety and the use of personal communications as evidence in entertainment-industry litigation.

The core issue is whether the production met legal obligations to prevent harassment and respond appropriately when concerns were raised.

As the case proceeds, it may influence how studios implement safety standards and manage disputes involving high-profile performers. The outcome will shape ongoing discussions about professional protections across film sets, where issues of power, perception and protocol increasingly intersect.