Viral headlines come and go, but the deaths of the ultra-wealthy tend to leave a different kind of footprint: investigators, families, insurers, business partners, and the public all pull at the same thread—what really happened, and who benefits now? In many cases, the official conclusion is clear. In others, the “official” story is only the first layer.

This list focuses on billionaires who died in tragic or suspicious circumstances—murders, disappearances, catastrophic accidents, or deaths ruled as suicide that remained controversial in public debate. No routine illness. No quiet old age. Just the cases that still spark questions (or at least uneasy fascination), even years later.

Date of birth: 6 August 1932

Place of birth: Beirut, Lebanon

Date of death: 3 December 1999

Place of death: Monte Carlo, Monaco

What happened: Edmond Safra, the billionaire private banker, died in a fire inside his Monaco penthouse. The official finding was that he died from smoke inhalation as the blaze spread, trapping him.

Official case outcome: Safra’s nurse, Ted Maher, was convicted in Monaco for arson causing death after admitting he started the fire as part of an attempt to stage a “heroic rescue.”

Why people still argue about it: Even with a conviction, the case has never fully settled in the public imagination. The story intersects with wealth, private security, banking secrecy, and claims around organised crime theories that circulated after Safra’s death—fuel that has kept interest alive, especially with renewed attention in late 2025.

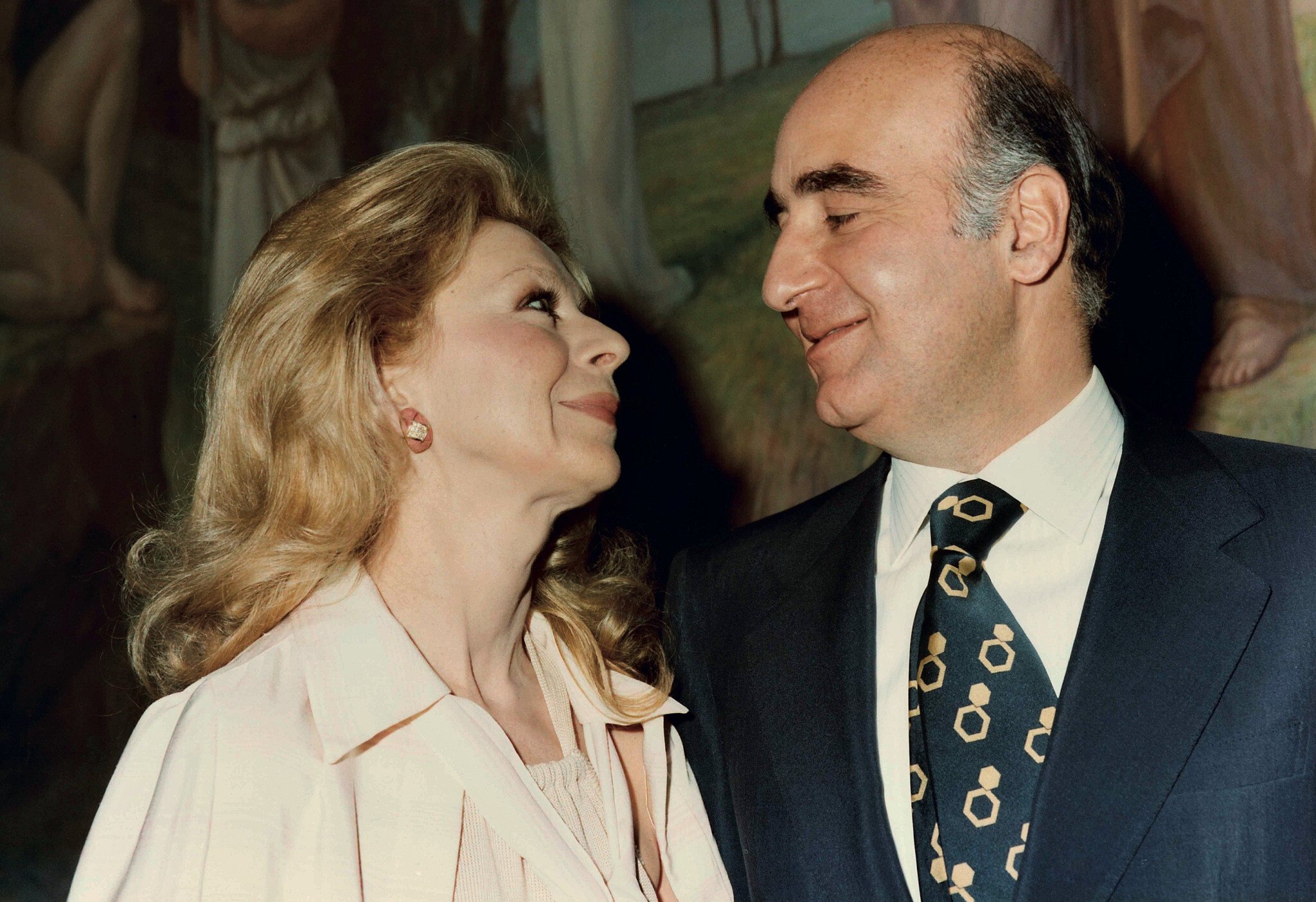

Who benefited / inheritance: Safra’s widow, Lily Safra, became the central steward of his legacy and wealth, later becoming widely known for high-profile philanthropy.

Date of birth: 21 February 1942

Place of birth: Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Date of death: 13 December 2017 (police believe), found 15 December 2017

Place of death: Toronto, Ontario, Canada

What happened: Barry Sherman, founder of pharmaceutical giant Apotex and a billionaire philanthropist, was found dead in his home. The confirmed cause of death was ligature neck compression—in plain terms, strangulation—and Toronto police ultimately treated it as a homicide investigation.

Official cause of death: Ligature neck compression (strangulation).

Why it remains disturbing: The murders drew national attention because of the victims’ profile, the unusual staging described publicly, and the long-running absence of arrests that kept the case in the public eye for years.

Who benefited / inheritance: Sherman’s wealth and estate became tied to his heirs and broader legal and corporate aftermath, with the family deeply invested in pushing back against early public speculation and pressing for answers.

Date of birth: 20 October 1947

Place of birth: Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Date of death: 13 December 2017 (police believe), found 15 December 2017

Place of death: Toronto, Ontario, Canada

What happened: Honey Sherman was found dead alongside her husband, Barry, in the same Toronto residence. Her cause of death was also ligature neck compression, and the case was treated as a homicide investigation.

Official cause of death: Ligature neck compression (strangulation).

Why her death matters in the story: Many high-profile cases collapse into one “headline name,” but the investigation repeatedly stressed two victims, and outside investigators publicly argued the scene did not fit simplistic narratives that circulated early on.

Who benefited / inheritance: As with Barry, the aftermath involved estate and family-level consequences, and the family’s public stance played a notable role in shaping media coverage.

Date of birth: 20 May 1964

Place of birth: Česká Lípa, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic)

Date of death: 27 March 2021

Place of death: Near Knik Glacier, Alaska, United States

What happened: Petr Kellner, the Czech Republic’s richest man and a Forbes-listed billionaire, died in a helicopter crash during a heli-skiing trip in Alaska.

Official cause of death: Death resulting from the helicopter crash; investigative reporting around the crash has included findings pointing to accident factors in difficult conditions.

Why it resonated globally: The scale of Kellner’s wealth and influence made the crash international news, and later reporting underscored how remote-location aviation accidents can become lethal fast, even when rescue eventually arrives.

Who benefited / inheritance: Kellner’s death triggered succession questions around the PPF group and the stewardship of his fortune, with family structures taking on greater public visibility in the aftermath.

Date of birth: 4 April 1958

Place of birth: Bangkok, Thailand

Date of death: 27 October 2018

Place of death: Leicester, England, United Kingdom

What happened: Thai billionaire Vichai Srivaddhanaprabha, owner of Leicester City FC, died when his helicopter crashed shortly after takeoff from the stadium. Official investigations reported mechanical failure factors, and later legal action and reporting kept the crash in public view.

Official cause of death: Death resulting from the crash and subsequent fire; investigative findings reported tail-rotor/control issues consistent with mechanical failure.

Why it stayed headline-worthy: A billionaire sports owner dying in a stadium-adjacent crash became a defining trauma event for the club and city, and the continuing legal and technical dispute has kept public interest alive years later.

Who benefited / inheritance: The King Power business empire and football club ownership continuity became immediate questions, with the family remaining central to legacy and control.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x409:751x411)/Thomas-H-Lee-dead-022323-3b9dcd91764e4fe6891ca0cdadb778a7.jpg)

Date of birth: 27 March 1946

Place of birth: New York City, New York, United States

Date of death: 23 February 2023

Place of death: New York City, New York, United States

What happened: Thomas H. Lee, a billionaire private-equity pioneer, died after being found at his Manhattan office. The New York City Medical Examiner recorded his death as a suicide caused by a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Official cause of death: Suicide by self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Why it hit the business world hard: Lee’s death was treated as a shock not because of mystery, but because it punctured a common myth around elite wealth and mental stability: that success insulates people from collapse.

Who benefited / inheritance: Estate planning and family inheritance structures became the practical aftermath, with the Lee family and philanthropic ties forming part of the public record around his legacy.

Date of birth: 16 June 1965

Place of birth: Ilford, London, England, United Kingdom

Date of death: 19 August 2024

Place of death: Off Porticello, Sicily, Italy

What happened: British tech entrepreneur Mike Lynch died when the superyacht Bayesian sank in extreme weather off Sicily. An inquest recorded his cause of death as drowning, and subsequent reporting tied the sinking to violent winds and rapid capsize dynamics.

Official cause of death: Drowning.

Why it became a global business tragedy: The incident blended modern wealth rituals—celebration travel, superyachts, high-profile guests—with the brutal physics of maritime disasters: when a vessel goes, it can go in seconds.

Who benefited / inheritance: Family inheritance and corporate legacy issues followed, amplified by the timing—Lynch’s death came after major legal drama around his business life, making the ending feel, to many, like an epilogue no one expected.

Date of birth: 18 March 1934

Place of birth: Dresden, Germany

Date of death: 5 January 2009

Place of death: Near Blaubeuren, Germany

What happened: Adolf Merckle, a German billionaire industrialist, died by suicide after the financial crisis and reported massive losses, including market turmoil tied to Volkswagen shares. Prosecutors and reporting described his death as occurring when he threw himself in front of a train.

Official cause of death: Suicide by train.

Why it still matters: Merckle’s case is often referenced as a stark illustration of market stress at the very top: even billionaire balance sheets can implode under leverage, panic, and reputation collapse.

Who benefited / inheritance: The Merckle family’s corporate interests continued through heirs and restructuring, a reminder that personal tragedy doesn’t stop the machinery of holdings and succession.

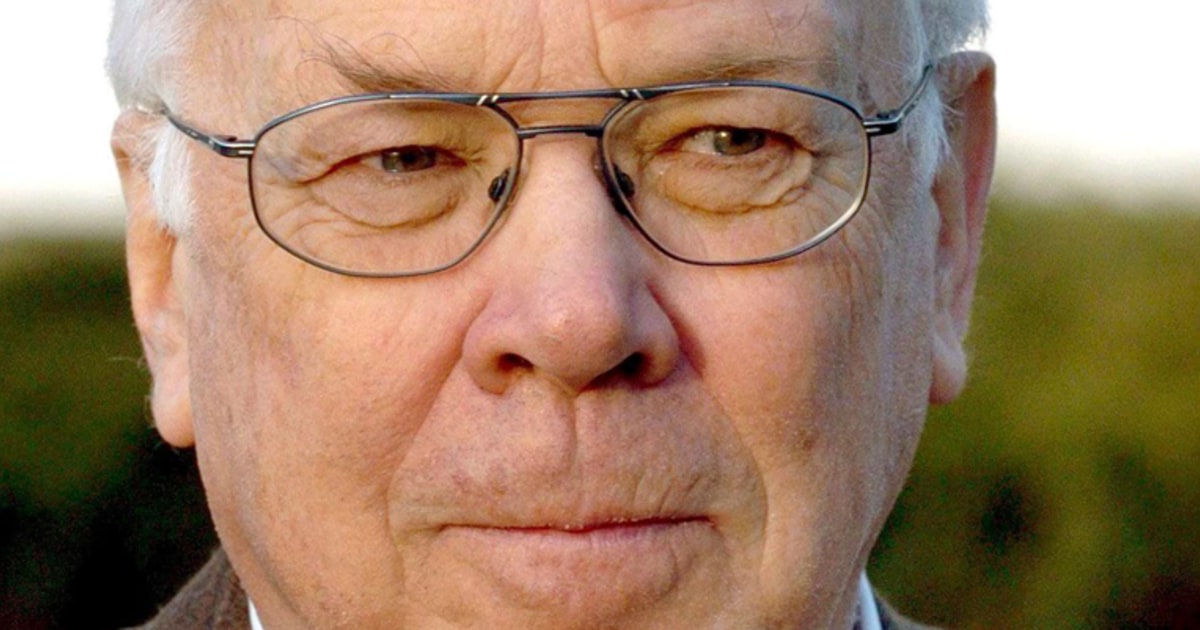

Date of birth: 23 January 1946

Place of birth: Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union

Date of death: 23 March 2013

Place of death: Sunninghill, Berkshire, England, United Kingdom

What happened: Exiled Russian oligarch Boris Berezovsky was found dead in a locked bathroom at his Berkshire home, with a ligature around his neck. A postmortem identified hanging as the cause of death, while police publicly treated the death as “unexplained” during investigation and the case became a magnet for speculation.

Official cause of death: Hanging (postmortem finding).

Why suspicion lingered publicly: Berezovsky’s political history, enemies, financial distress, and the “locked-room” optics made the case one the public never accepted as emotionally simple, even where official findings pointed one direction.

Who benefited / inheritance: Berezovsky’s finances were widely reported as strained toward the end, with legal and debt pressures shaping public discussion of his final months.

Date of birth: 2 March 1960

Place of birth: Tacoma, Washington, United States

Date last seen: 7 April 2018

Place last seen: Klein Matterhorn area, Swiss Alps, Switzerland

Declared dead: 14 May 2021 (German court)

What happened: Karl-Erivan Haub, a German-American-Russian billionaire retail executive, vanished while ski mountaineering in the Swiss Alps. After years without confirmed recovery, a German court officially declared him dead.

Official status: Missing, then legally declared dead.

Why the story became bigger than a disappearance: A billionaire disappearing on a mountain produces an almost inevitable second narrative: accident versus something more deliberate. Public reporting and later investigations have kept the case alive well beyond the typical missing-person cycle.

Who benefited / inheritance: With Haub gone, succession and control questions naturally followed for the business empire and family governance.

Were all of these people confirmed billionaires?

Yes. Each person on this list is widely reported as a billionaire or described in major reporting as such at the time of their death or disappearance, including multiple cases directly described as billionaire in mainstream coverage.

Why include suicides if the point is “suspicious”?

Because the list is “tragic or suspicious circumstances,” and in several cases the public controversy comes from the surrounding context, stakes, and unanswered questions—even when official findings are clear.

Why no routine illness deaths?

Because you explicitly asked for deaths that were not mundane illness, and the premise of the article is the circumstances and aftermath.

Should the article include “last known location” and theories?

Only where it’s relevant and responsible. For disappearances like Haub, the last known location is central. For deaths with official causes, “theories” should be framed as public speculation, not asserted fact.

To most people, the idea that reporters can access official death records feels intrusive — especially when families haven’t spoken publicly.

Under U.S. public records law, certain government documents become accessible once they are created as part of an official investigation.

That principle is now drawing attention following reporting on the death of James Ransone, after a county medical examiner confirmed the manner of death. The disclosure does not determine intent beyond medical classification, assign blame, or override a family’s other privacy rights.

Medical examiner and coroner reports are government records. Once finalized, core findings are often public under state transparency laws. Fame, sensitivity, or family preference generally does not control release.

Public record does not mean full disclosure: Summary findings may be released, while photographs, detailed notes, or investigative materials can remain restricted or redacted.

Next-of-kin consent isn’t required: Access is governed by statute, not family approval.

Timing is procedural: Records are typically unavailable until the examiner completes and certifies the determination.

In practice, medical examiners and coroners are public officials. When they certify a death, they generate records as part of their official duties. Courts generally presume these records are open because transparency ensures accountability and consistency in death investigations.

Legally, this means that once an investigation reaches a defined procedural endpoint—often certification of cause and manner of death—core documents can be requested by the public or media. The scope and timing vary by state, but the baseline rule is the same: government records are open unless a specific exemption applies.

Because these records are public, confirmed facts can be reported quickly, which may intensify attention before families choose to speak. That reality can influence litigation strategy, public statements, memorial planning, and charitable efforts. For public figures and private individuals alike, it underscores how privacy expectations change once an official investigation concludes.

This disclosure is a procedural step, not a judgment. It does not predict civil or criminal liability, imply wrongdoing, or determine responsibility. It reflects how transparency law operates once a government process is completed.

Most people expect grief to pause bureaucracy. The law doesn’t work that way. Open-records rules apply uniformly—whether the subject is famous or unknown—to prevent selective secrecy and ensure equal treatment.

For employers, business owners, litigants, and families, the same principle applies: when a government agency creates records as part of its duties, those records may become public. Understanding where privacy ends and transparency begins helps people prepare for disclosure and avoid being blindsided at a vulnerable moment.

Can a family block the release of a medical examiner’s report?

Usually no. Families may request redactions in limited circumstances, but the authority to release records is set by statute.

Why can the media get this information at all?

Because the records belong to the government, not the individual. Transparency laws prioritize public access once official determinations are finalized.

Does a public finding mean there will be legal action?

No. Medical examiner findings are medical classifications, not legal judgments.

Why does this apply even when the death is deeply personal?

Open-records rules apply consistently to prevent case-by-case secrecy, even when circumstances are sensitive.

Is this different outside the United States?

Yes. Disclosure rules vary widely by jurisdiction, but many U.S. states favor openness after certification.

If you or someone you know is struggling, help is available. In the U.S., the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline can be reached by calling or texting 988. Support is confidential and available 24/7.

👉👉 Related: Why Florida Law Allowed a Parkland Shooting Survivor to Legally Buy a Gun

Donovan Joshua Leigh Metayer, a survivor of the 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, died by suicide earlier this month at the age of 26, according to his family.

Metayer had lived for years with the psychological aftermath of the attack, alongside serious mental health challenges that required ongoing treatment and, at times, involuntary intervention. His death has renewed public scrutiny of how mental health law, firearm restrictions, and time-limited court orders intersect in Florida.

In the weeks before his death, Metayer was legally permitted to purchase a handgun after a prior court-ordered restriction expired. For many readers, that fact is difficult to reconcile with his documented history of mental health crises and previous involuntary treatment. The case raises a deeply unsettling question: how can someone who has been subject to mental health holds later regain the legal right to buy a firearm?

Under Florida law, involuntary mental health treatment and firearm restrictions are governed by specific statutes with defined time limits and procedural safeguards. Those measures are designed to address immediate risk, not to impose permanent legal disability. Understanding how those rules operate — and where their limits lie — is essential to understanding what happened here.

Florida’s mental health and firearm laws allow courts to impose temporary restrictions during periods of acute crisis. Once those orders expire, firearm eligibility can be restored unless a new legal action is taken. The law focuses on present risk, not past diagnosis.

Florida permits involuntary mental health evaluation and treatment when a person is believed to pose an immediate danger to themselves or others. These holds are intended as crisis-stabilisation tools, allowing clinicians to assess risk and provide short-term care.

Crucially, an involuntary hold does not function as a criminal conviction, nor does it automatically result in long-term civil penalties. In practice, the legal system treats these interventions as temporary responses to acute conditions, not as determinations of permanent incapacity.

Courts may order additional protections during or following such treatment, including restrictions on firearm access. But those protections exist only for as long as the law allows — and only if the legal criteria continue to be met.

Florida law allows courts to issue Risk Protection Orders (RPOs), sometimes called “red flag” orders, when evidence suggests that a person poses a significant danger. These orders can temporarily prohibit firearm possession and purchase.

However, RPOs are time-limited by design. They must be reviewed, renewed, or replaced through additional legal proceedings. If no extension is sought — or if a court determines the legal threshold is no longer met — the order lapses automatically.

When that happens, firearm eligibility is restored under the law, even if the individual has a history of mental health treatment. The system prioritises due process and current evidence of risk, rather than indefinite restrictions based on prior crises.

Involuntary mental health treatment does not permanently remove firearm rights

Firearm restrictions require active, ongoing court orders

Courts must rely on legally admissible evidence of present danger

Once an order expires, eligibility is restored unless new action is taken

It is critical to distinguish legal process from personal outcome. The expiration of a firearm restriction does not imply that a person is “well,” safe, or free from risk. It reflects only that the legal criteria for continued restriction were no longer met or pursued within the statutory framework.

Similarly, the existence of safeguards does not guarantee that tragedy will be prevented. The law can manage risk, but it cannot predict individual outcomes with certainty.

To many people, it feels intuitive that someone who has experienced repeated mental health crises should remain indefinitely restricted from accessing firearms. The law, however, does not operate on intuition or hindsight. It operates on defined thresholds, evidence standards, and constitutional protections.

Florida’s system is designed to balance public safety with individual rights, requiring courts to reassess restrictions rather than impose them permanently. That balance can feel deeply uncomfortable when it collides with real-world loss.

This case has implications far beyond one family or one tragedy. It highlights the limits of time-bound legal safeguards, the challenges of monitoring ongoing risk, and the gaps that can emerge when mental health treatment, court oversight, and firearm regulation operate on separate tracks.

For families, clinicians, and policymakers, it raises difficult questions about whether current laws adequately address long-term vulnerability — and whether additional mechanisms are needed to bridge the space between crisis intervention and lasting protection.

Can someone regain gun rights after involuntary mental health treatment?

Yes. In Florida, involuntary treatment alone does not permanently remove firearm eligibility. Restrictions depend on active court orders.

Why don’t firearm bans last indefinitely in these cases?

Because the law requires ongoing legal justification. Permanent restrictions typically require criminal convictions or separate judicial findings.

Does an expired Risk Protection Order mean the system failed?

Not necessarily. It means the legal process reached its endpoint under current evidence and procedure, not that risk no longer existed.

Could the order have been extended?

Only if a new legal action was filed and supported by sufficient evidence within the required timeframe.

Does this case change Florida law?

No. But it adds to a growing public debate about whether existing safeguards are sufficient.

If you or someone you know is struggling, confidential mental health support is available through local services and national helplines.

This article explains legal processes and public-interest implications. It does not speculate on personal intent, assign blame, or offer legal advice.

When billionaire banker Edmond Safra died in his Monaco penthouse in the early hours of December 3, 1999, the initial explanation sounded straightforward: a fire, smoke inhalation, a tragic accident.

But almost immediately, the facts refused to align. Safra was one of the most security-conscious financiers on earth, living inside a residence engineered to withstand kidnappings and assassinations. And yet, he died not because help never arrived—but because help could not reach him in time.

More than twenty-five years later, renewed interest sparked by Netflix’s Murder in Monaco has brought the story back into public conversation. Much of the coverage focuses on Ted Maher, the nurse convicted of arson causing death. What’s still missing from most retellings is the larger truth: this case sits at the intersection of extreme security, institutional hesitation, and narrow legal framing—a convergence that turned a survivable emergency into a fatal one.

This article asks the questions many summaries don’t, answers what can be answered, and explains why the rest still matters.

Edmond Safra was born in Beirut on August 6, 1932, into a Sephardic Jewish banking family whose trading roots stretched back centuries. By his teens, he was immersed in finance; by his twenties, he was building banks across Europe and South America. Over decades, he founded and controlled institutions including Republic National Bank of New York and Trade Development Bank, becoming a trusted adviser to governments, institutions, and ultra-wealthy clients.

Safra’s wealth brought influence—and suspicion. For years, rumors circulated linking his banks to money laundering and organized crime. Courts later ruled those allegations defamatory or unsupported, but the reputational toll lingered. Safra responded by retreating further behind layers of protection. By the 1990s, his life was defined by privacy, ritual, and security protocols designed for worst-case scenarios.

As his Parkinson’s disease progressed, Safra required constant medical care. That necessity introduced private nurses into his most secure spaces—people vetted for clinical competence, not crisis management inside fortress-like residences.

Ted Maher’s life could not have been more different. Raised in upstate New York, he served as a medic with the U.S. Army’s Special Forces before training as a registered nurse. He worked in neonatal intensive care at Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital—skilled, disciplined, and far removed from the world of billionaires.

Through a chance connection involving Safra’s extended family, Maher was offered a lucrative position on Safra’s private nursing staff, earning more than $200,000 a year and splitting time between New York and Monaco. He spoke no French. He had no background navigating elite European security systems. He had been employed for months, not years, when the fire occurred.

That context matters, because it frames what happened next not just as a crime, but as a collision between human error and an unforgiving system.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(739x272:741x274):format(webp)/Ted-Maher-2002-121825-1093a52e2b06410793a4f5a7511874a8.jpg)

Ted Maher on December 2, 2002.

In the early morning hours of December 3, 1999, Maher reported that intruders had attacked him inside the penthouse. Safra and another nurse, Vivian Torrente, retreated into a steel-reinforced bathroom designed to function as a panic room. Elsewhere in the apartment, a fire began.

Police arrived quickly. Firefighters were dispatched. And then time slipped away.

The penthouse was protected by reinforced doors, layered alarms, and protocols meant to repel armed attackers. Responders treated the scene as a potential ongoing threat. Entry was delayed. Decisions were cautious and fragmented. The very features designed to keep Safra safe prevented rapid rescue.

When authorities finally breached the apartment hours later, Safra and Torrente had died from smoke inhalation.

Within days, Monaco authorities concluded there were no intruders. Investigators alleged Maher had staged the attack, injured himself, and started the fire to appear heroic and secure his job. Maher confessed, reenacted events, and was charged with arson causing death—a crime that does not require intent to kill under Monaco law.

In December 2002, he was convicted and sentenced to ten years in prison.

Legally, the case was resolved. Historically—and morally—it was not.

Aug. 6, 1932 — Edmond Safra is born in Beirut, Lebanon.

1947 — At age 15, Safra is sent to Milan, where he begins gold and currency trading.

1954 — Safra relocates to Brazil, expanding banking operations in South America.

1966 — Safra founds Trade Development Bank in Geneva.

1970s–1980s — Safra becomes a dominant figure in global private banking.

1983–1988 — Corporate disputes and reputational battles shape Safra’s security posture.

1990s — Safra intensifies personal security amid rumors and legal scrutiny.

Late 1990s — Safra’s Parkinson’s disease progresses; private nursing care becomes essential.

Summer 1999 — Ted Maher joins Safra’s nursing staff in Monaco.

Dec. 3, 1999 (early morning) — Fire breaks out in Safra’s Monaco penthouse; Safra and Vivian Torrente retreat to a panic room.

Dec. 3, 1999 (hours later) — Firefighters breach the residence; Safra and Torrente are found dead from smoke inhalation.

Dec. 6, 1999 — Monaco police announce Maher’s confession narrative.

Oct. 29, 2000 — The Guardian publishes a major investigative feature highlighting inconsistencies and unanswered questions.

Dec. 2002 — Maher is convicted of arson causing death and sentenced to ten years.

Jan. 2003 — Maher attempts to escape custody and is quickly recaptured.

Oct. 2007 — Maher is released from prison.

March 2008 — Maher recants elements of his confession in U.S. media interviews, alleging coercion.

2013 — Maher’s nursing license is revoked in Texas.

2022–2023 — Maher (now using the name Jon Green) is convicted of forgery-related crimes in the U.S.

March 2025 — Maher is found guilty in a murder-for-hire case.

July 2025 — He is sentenced to an additional nine years in prison.

Dec. 17, 2025 — Netflix releases Murder in Monaco, reigniting public scrutiny.

The most revealing aspect of Safra’s death is not who was convicted, but what was never fully examined.

Safra’s penthouse was so secure that emergency responders could not act decisively. Police treated the scene as an active threat rather than a rescue. Firefighters waited for authorization. No single authority assumed command. Each delay compounded the danger.

The panic room—a space designed to isolate Safra from harm—became a sealed chamber of smoke. Its purpose worked against him once fire entered the equation.

By focusing narrowly on Maher’s act of starting the fire, the legal process avoided confronting a harder truth: even reckless behavior does not have to be fatal if systems function properly. No institution—police, fire services, building security—faced criminal scrutiny. No systemic reforms followed.

Despite a conviction, unresolved issues remain central to understanding the case. Investigators reportedly identified more than one fire origin. Early accounts conflicted on whether Safra communicated with his wife or security while trapped. Security recordings were described as unavailable or nonfunctional. And it remains unclear why it took hours to breach a bathroom in one of the most heavily policed places on Earth.

These questions do not overturn the verdict. They explain why doubt persists.

After his release in 2007, Maher returned to the United States, changed his name to Jon Green, lost his nursing license, and was later convicted of additional crimes, including murder-for-hire. In July 2025, he received an additional nine-year sentence and is currently incarcerated in New Mexico, reportedly suffering from late-stage throat cancer.

His later crimes harden public perception—but they do not retroactively explain what happened in Monaco.

Legally, Edmond Safra died because of arson causing death. Practically, he died because smoke filled a room rescuers could not reach. Historically, his death represents something more complex: a moment when fear, secrecy, and over-securitization combined with institutional hesitation to produce a fatal outcome.

Safra did not die because help never came.

He died because help could not reach him in time.

That distinction—uncomfortable and unresolved—is why this case still matters, and why it continues to rank among the most baffling deaths in modern financial history.

👉👉 Related: Top 10 Billionaires Who Died in Tragic or Suspicious Circumstances 👈👈

Kyle Chrisley, the eldest son of Todd Chrisley and Julie Chrisley, was arrested Saturday night in Rutherford County, Tennessee, on a sweeping list of criminal charges that go far beyond a routine celebrity arrest.

According to booking records, Kyle was taken into custody by the Rutherford County Sheriff’s Office around 7 p.m. Saturday and later booked into the Rutherford County Adult Detention Center. The charges include domestic assault, public intoxication, disorderly conduct, resisting arrest, three counts of assaulting a first responder, and three counts of retaliation for past actions.

While authorities have not released a full incident report, the scope of the charges alone places Kyle’s case in a far more serious legal category than a standard misdemeanor arrest.

Kyle Chrisley has not been convicted of any of the charges, and all allegations remain unproven at this stage.

Not all assault cases are treated equally under Tennessee law. Allegations involving first responders and retaliation carry enhanced penalties and signal that prosecutors believe the incident involved deliberate escalation rather than a momentary lapse in judgment.

Assaulting a first responder—such as a sheriff’s deputy or EMT—can elevate charges to felony-level exposure, depending on the facts alleged. Prosecutors must show the accused knowingly assaulted someone acting in an official capacity. If sustained, convictions can result in mandatory jail time, longer probation periods, and permanent criminal records.

The retaliation for past actions charges are particularly unusual. These typically allege that a defendant threatened or harmed someone because of something they previously did—often related to law enforcement, testimony, or prior legal disputes. Officials declined to clarify who the alleged victims were, but the inclusion of these counts suggests the case may involve more than a single spontaneous confrontation.

To secure convictions, prosecutors will need to establish distinct legal elements for each charge, including:

Domestic assault: Proof of intentional or knowing physical contact or threat against a qualifying domestic victim.

Assault on a first responder: Evidence the alleged victim was performing official duties and that Kyle knew their status.

Resisting arrest: Proof that Kyle intentionally prevented or obstructed a lawful arrest.

Retaliation for past actions: Evidence of a causal link between the alleged conduct and a prior action taken by the victim.

Each charge stands on its own, meaning even if some counts are dismissed, others could still proceed.

Kyle Chrisley rose to public attention through his family’s hit reality series Chrisley Knows Best, but he was largely absent from later seasons. Unlike his siblings, Kyle has long maintained a strained relationship with his parents, marked by periods of estrangement, reconciliation, and very public conflict.

Now in his early 30s, Kyle has spoken openly about struggles with bipolar disorder, substance abuse, and financial instability. His turbulent personal life has frequently spilled into public view through social media disputes, custody battles, and prior criminal cases, making him one of the more controversial figures associated with the Chrisley family brand.

No. Kyle was arrested just over a year ago on an aggravated assault charge. That case later became the basis for a civil lawsuit he filed against Rutherford County and two sheriff’s deputies, seeking approximately $1.7 million in damages.

In that lawsuit, Kyle alleged his arrest was unlawful and violated his civil rights. That history may now take on new relevance. Prosecutors could argue a pattern of behavior, while defense attorneys may raise concerns about prior law enforcement interactions, alleged bias, or procedural misconduct.

Several factors make this arrest more consequential than Kyle’s prior run-ins with the law:

Multiple charges from a single incident

Three separate counts involving first responders

Rare retaliation allegations

An active or recent civil dispute with the sheriff’s office

Taken together, these elements increase both legal exposure and prosecutorial leverage during plea negotiations.

Kyle’s arrest comes the same year his parents were pardoned by Donald Trump after serving sentences related to bank fraud and tax evasion convictions.

Legally, the pardon has no bearing on Kyle’s case. Each defendant is treated individually under criminal law. However, the Chrisley family’s extensive legal history may amplify media attention and public scrutiny surrounding Kyle’s proceedings.

Kyle is expected to proceed through the standard Tennessee criminal process, which typically includes:

An initial court appearance and bond determination

Formal charging decisions by prosecutors

Discovery and pretrial motions

Possible plea negotiations or trial

Cases involving first responders rarely resolve quietly, and outcomes often hinge on body-camera footage, witness testimony, and medical or toxicology reports.

TMZ reports that Kyle’s attorney has not yet responded to requests for comment.

Could Kyle Chrisley face jail time?

Yes. Convictions involving assault on a first responder can carry mandatory incarceration.

Does his prior lawsuit help or hurt his defense?

It could cut both ways, depending on whether the defense frames it as evidence of bias or prosecutors argue retaliation.

Will this affect family or custody matters?

Domestic assault allegations often trigger protective orders and can influence family court decisions.

Is fame a factor in court?

Legally, no. Practically, high-profile defendants often face less judicial patience for repeat conduct.

Kyle Chrisley’s arrest is not just another celebrity police blotter headline. With allegations involving first responders, retaliation, and a documented history of legal conflict, the case carries significant legal risk and could mark a turning point in his long-running struggles with the justice system.

As the case unfolds, the details—still largely undisclosed—will determine whether this becomes another chapter in the Chrisley family’s legal saga or a far more consequential reckoning.

Under US law, the Department of Justice may release investigative materials — including photographs and documents — without making findings of criminal wrongdoing against the individuals depicted.

Many people assume that appearing in DOJ-released files means criminal guilt, but US law does not work that way. That legal process has drawn intense public scrutiny following the release of Epstein-related files that include images of Bill Clinton. The disclosure of such material does not determine guilt, imply criminal conduct, or establish legal liability.

The Justice Department released a large, heavily redacted cache of materials connected to investigations involving Jeffrey Epstein, who died in federal custody in 2019 while awaiting trial on sex-trafficking charges. Epstein had previously pleaded guilty in Florida state court in 2008 to soliciting a minor for prostitution and later faced federal charges alleging sex trafficking of minors.

The newly released materials include photographs and travel records showing Epstein with a number of prominent figures, including former President Clinton. Some images depict Clinton in social settings with unidentified women. Clinton has not been charged in connection with Epstein’s crimes and has denied wrongdoing.

DOJ document releases may include unproven, unadjudicated, or purely contextual materials gathered during investigations. Disclosure can be required by court order, statute, or congressional mandate. Release does not equal accusation, and inclusion does not equal guilt.

Disclosure is not a finding of criminal responsibility

Photographs and social association are not evidence of a crime

Redactions protect victims, witnesses, and privacy interests — not specific individuals

Investigative files often include people who were never suspects

In practice, federal agencies may be compelled to release investigative records even when no charges were filed or when investigations are closed. Courts and Congress can require disclosure in the interest of transparency, particularly in historically significant or high-profile matters.

Legally, this means materials can become public without the government asserting that a crime occurred, let alone that a particular person committed one. The evidentiary standard for disclosure is far lower than the standard required to bring criminal charges.

US criminal law does not impose liability based on proximity, travel, or social interaction alone. To charge someone with a crime, prosecutors must establish specific unlawful acts, intent, and jurisdictional elements — none of which can be inferred solely from photographs or presence.

This is why individuals may appear repeatedly in investigative files without ever being charged or formally accused.

This release is procedural, not adjudicative. It does not predict future charges, imply misconduct, or alter the legal status of anyone depicted. Courts routinely stress that investigative disclosures should not be mistaken for findings of fact or determinations of guilt.

Failing to separate procedure from outcome is one of the most common sources of public misunderstanding in high-profile cases.

For public figures, business leaders, and private individuals alike, appearing in disclosed investigative materials does not create criminal exposure on its own. Employers, institutions, and the public should understand that legal responsibility is established in court — not through document dumps or photo releases.

More broadly, these cases illustrate how transparency mechanisms can clash with public assumptions about guilt, particularly when serious crimes are involved.

Can someone be criminally liable just for appearing in DOJ files?

No. Criminal liability requires proof of specific unlawful conduct, not mere inclusion in investigative materials.

Why does the DOJ release files if no charges were filed?

Releases may be required by law, court order, or congressional mandate, even when investigations do not result in prosecution.

Do redactions mean the government is hiding evidence?

Not necessarily. Redactions often protect victims, witnesses, privacy rights, or sensitive investigative methods.

Does association with a criminal prove wrongdoing?

No. Association alone is not a crime under US law.

Could charges still be filed in the future?

Only if prosecutors obtain admissible evidence meeting the legal threshold for prosecution. Disclosure alone does not change that standard.

The legal principles discussed here apply broadly under US criminal and constitutional law and are not limited to any individual named in released materials.

If you are dealing with persistent unwanted contact, California law allows courts to extend restraining orders and expand who they protect when the risk has not gone away.

This legal process has drawn attention following a renewed restraining order involving Natalia Bryant, which was extended for several years and expanded to include immediate family members. This article explains how restraining orders work for anyone facing ongoing harassment — not the facts or merits of the underlying dispute — and the ruling does not determine criminal guilt or civil liability.

Many people are surprised to learn how long these orders can last, and how easily they can be expanded when courts believe protection is still necessary.

Under California law, a civil harassment restraining order may be renewed if a court finds that fear or risk remains. Judges can also include family members when contact with them is used to reach the protected person. These orders are preventive safeguards, not punishments.

Restraining orders operate under civil law, not criminal law. That means courts do not need proof beyond a reasonable doubt or a criminal charge to act. Instead, judges assess patterns of behaviour and whether restrictions are still necessary to prevent future harm.

This is why restraining orders can be extended — or expanded — even when no criminal case is pending.

Whether recent behaviour shows continued unwanted contact or fixation

Whether indirect communication undermines the original order

Whether family members face exposure due to proximity or shared appearances

Courts do not decide criminal guilt, intent, or who is “at fault”

Most California civil harassment restraining orders last up to five years. As an order approaches expiration, the protected person may ask the court to renew it by showing that the risk has not meaningfully changed.

In everyday terms, courts focus on what has happened since the order was issued. Even limited contact can matter if it suggests boundaries are no longer being respected. The court’s role is prevention — not punishment.

Courts recognise that harassment is not always direct. If someone attempts to make contact through relatives, workplaces, or public events, judges may expand the order to close those access points.

This applies whether the person involved is well known or not. The legal standard is risk — not status.

Extending or expanding a restraining order does not mean a crime was committed. It does not establish liability or predict the outcome of any future legal action. These orders exist to reduce risk and set enforceable boundaries, nothing more.

For example, a small business owner dealing with repeated unwanted contact from a former client could rely on the same legal process — even if messages are sent through staff or family members. Courts assess behaviour and risk, not personal background.

The same principles apply to employees, freelancers, and anyone whose work or family connections create access points that can be exploited.

Can a restraining order be extended without criminal charges?

Yes. Courts may renew restraining orders based on ongoing fear or violations, even if no criminal case exists.

Can family members really be protected too?

Yes. If contact with family members is being used to bypass restrictions, courts can include them.

Can you go to jail for violating a restraining order by mistake?

Yes. Violating a restraining order can carry criminal consequences even if the person claims misunderstanding. Courts expect strict compliance.

Does a restraining order mean someone is guilty of a crime?

No. These are civil protective measures, not criminal judgments.

How long can a restraining order last in California?

Orders can last up to five years at a time and may be renewed if the court believes protection is still necessary.

The legal principles discussed here apply broadly under California civil procedure and are not limited to high-profile cases.

The settlement highlights how legally required abuse reports allegedly went unfiled before an 11-year-old girl died, raising broader concerns about child-protection systems in San Diego.

San Diego city and county agencies agreed to pay a combined $31.5 million to settle a civil lawsuit alleging that legally required child-abuse reports were not made before the 2022 death of 11-year-old Arabella McCormack. The agreement, announced Friday, also includes payments from a homeschooling program and a church and was filed on behalf of Arabella’s two younger sisters, who were living in the same household at the time and are now in foster care.

The settlement matters beyond this case because it centers on how mandated reporting laws are supposed to work—and what can happen when warning signs of abuse are allegedly missed or not acted on. Under California law, certain professionals must report suspected abuse quickly to trigger intervention. The civil agreement does not determine criminal guilt, but it explains how failures in that reporting system can lead to significant legal and financial consequences for public agencies and institutions.

In short: California law requires certain professionals to report suspected child abuse immediately, based on reasonable suspicion. When those reports are not made, agencies and institutions can face civil liability if harm later occurs. This settlement reflects that legal exposure, not a criminal verdict.

For many readers, the question is simple: how many chances were there to intervene before help arrived?

California’s Child Abuse and Neglect Reporting Act requires teachers, social workers, school administrators, and other designated professionals to act when they reasonably suspect a child is being abused or neglected. The law does not require certainty or proof. Instead, mandated reporters must make an initial report immediately or as soon as practicable by telephone, followed by a written report within 36 hours.

The goal is early intervention. When reports are made promptly, child protective services or law enforcement can investigate, assess safety, and take protective steps. When reports are delayed or never filed, the opportunity to intervene may be lost.

According to public court filings, the settlement includes $10 million from the city of San Diego, $10 million from San Diego County, $8.5 million from Pacific Coast Academy, and $3 million from Rock Church. Pacific Coast Academy oversaw Arabella’s homeschooling, and her adoptive mother held a leadership role at Rock Church.

The agreement resolves the civil claims against those entities without a trial or admission of wrongdoing. Because the beneficiaries are minors, the settlement will be subject to court oversight to determine how the funds are held and distributed for the sisters’ long-term care and support.

Takeaway: The civil case is closing, but how the money is managed will remain under judicial supervision.

👉 Related: Why the Tyler Skaggs wrongful-death case against the LA Angels settled during jury deliberations 👈

Sheriff’s deputies responded on Aug. 30, 2022, to a report of a child in distress at the family’s home. Authorities said Arabella was found severely malnourished with visible bruising and was taken to a hospital, where she later died.

The lawsuit alleged that multiple agencies and organizations encountered warning signs over time but failed to report suspected abuse as required. The focus of the civil case was not a single missed moment, but an alleged pattern of breakdowns across systems designed to protect children.

Takeaway: The lawsuit centers on whether safeguards meant to detect abuse were activated in time.

Arabella’s adoptive mother, Leticia McCormack, and her parents, Adella and Stanley Tom, have been charged with murder, conspiracy, child abuse, and torture. All three have pleaded not guilty, and the criminal case remains ongoing in San Diego County Superior Court.

Civil settlements do not determine criminal responsibility. Prosecutors must prove the criminal charges beyond a reasonable doubt, a higher standard than applies in civil lawsuits.

Takeaway: The settlement does not affect the outcome or timeline of the criminal case.

California has faced repeated scrutiny over how child-abuse reports are tracked and acted upon. A California State Auditor report has previously described the state’s reporting and data systems as fragmented, noting that reports are not always consistently forwarded or recorded across agencies.

Cases involving homeschooling can present additional challenges because children may have fewer daily contact points with teachers or medical professionals. In those situations, mandated reporters who do have contact may play an especially critical role.

Takeaway: The settlement lands amid ongoing concerns about how reliably child-protection systems function across counties.

For Arabella’s two surviving sisters, the settlement is intended to provide long-term stability, including support for education, housing, and care following severe trauma. Their attorney has said the girls are now 9 and 11 and are in good health.

For schools, churches, and public agencies, the case underscores that mandated reporting is not merely a policy expectation—it is a legal duty with real consequences when it is not fulfilled.

Takeaway: The outcome reinforces that early reporting obligations are central to child safety and institutional accountability.

State guidance instructs mandated reporters to contact a designated agency—such as child protective services or law enforcement—immediately by phone when abuse is suspected, followed by a written report within 36 hours using the state’s Suspected Child Abuse Report form (SS-8572).

Members of the public who believe a child is in immediate danger should contact emergency services. For non-emergency concerns, counties operate child protective services hotlines with publicly listed numbers.

Takeaway: The reporting system is designed for speed, because delays can reduce the chance of intervention.

No. Civil settlements commonly resolve claims without admissions of liability or a court judgment on fault.

The funds are designated for Arabella’s two younger sisters and will be distributed under court supervision to protect their interests.

The lawsuit alleged those organizations had contact with the child and failed to report warning signs as required by law.

No. The criminal case proceeds independently under a different legal standard.

After court approval, funds are typically placed in protected accounts or structured arrangements rather than paid as a lump sum.

The settlement must still complete court approval steps related to minors’ funds. Separately, the criminal case against the adoptive caregivers will continue through pretrial proceedings and any trial schedule set by the court.

Takeaway: Civil claims are nearing resolution, while criminal accountability remains undecided.

This case illustrates how child-protection laws rely on early reporting to prevent irreversible harm. It affects two children directly, but it also raises broader questions about how mandated reporting systems function when children have limited outside visibility. As the criminal case continues, attention will remain on whether existing safeguards are sufficient—and whether they are being followed.

When police responded to an early-morning welfare call at a Frisco, Texas residence shortly before 6 a.m., they were not investigating a reported crime. Yet by the end of the response, former UCLA standout and NFL linebacker Myles Jack was in custody, injured, and facing a felony charge that has confused many readers: deadly conduct involving a firearm — even though no one was shot or physically harmed.

That apparent contradiction has driven much of the public reaction. How can someone be charged with a serious firearm offence when no one was injured? The answer lies in how Texas criminal law is written to address risk to public safety, not just physical harm after the fact.

Under Texas law, deadly conduct focuses on danger, not damage. Prosecutors do not need to show that anyone was hurt, targeted, or even intended to be harmed. Instead, the legal threshold is whether a firearm was allegedly discharged in a manner that created a substantial and unjustifiable risk to others.

At this stage, the charge is an allegation only, not a determination of guilt.

This is why deadly conduct charges can be filed even when no one is shot and no victim is identified.

According to police statements, officers were dispatched to the residence after receiving a welfare concern. After arriving, officers reported hearing gunshots from inside the home. Based on that perceived risk, officers established a perimeter and evacuated nearby residences as a precaution.

During the response, a second-story window was broken and Jack allegedly exited the residence, falling to the ground below. He was taken into custody several hours later and transported to hospital with non-life-threatening injuries. A subsequent search of the residence reportedly found no other occupants inside. The investigation remains ongoing.

These details matter legally because Texas firearm statutes allow law enforcement to intervene at the moment a serious public risk is perceived — not after someone is injured.

To many readers, the charge may feel counter-intuitive. No injuries were reported, and authorities have not alleged that anyone was deliberately targeted. But under Texas law, that gap between what happened and what could have happened is precisely where deadly conduct statutes operate.

In practice, courts typically look at:

Where a firearm was allegedly discharged

Who might reasonably have been nearby

Whether the conduct created immediate danger to the public or responding officers

The statute is designed to prioritise prevention over aftermath.

Legally, intent, motive, and injury are not required at the charging stage.

No.

A deadly conduct charge:

Does not establish guilt or criminal intent

Does not require proof that anyone was shot or harmed

Does not predict whether the case will go to trial

Does allow police and prosecutors to secure custody, set bail, and continue investigating

In practical terms, firearm-related charges often function like a legal pause button — allowing authorities to stabilise a potentially dangerous situation first and determine responsibility later.

With charges filed, prosecutors will review police reports, forensic evidence, and any witness statements before deciding how the case proceeds. Charges may be amended, reduced, or dismissed as the investigation develops.

Defence counsel may challenge whether the alleged conduct meets the statutory definition of deadly conduct or whether the available evidence supports the charge as filed.

Bail, which was set at $100,000, is not a judgment on guilt. It is a procedural mechanism designed to manage public safety and ensure court appearances while the case remains pending.

This stage of the case is procedural, not determinative. Filing charges does not imply guilt, predict conviction, or establish criminal liability. It simply reflects the state’s view that further legal scrutiny is warranted.

That separation between accusation and outcome is a core protection within the criminal justice system — including in high-profile cases.

For the public, the case highlights how firearm laws are enforced based on perceived risk rather than final harm. For homeowners, it shows how welfare calls can escalate rapidly when firearms are involved. And for public figures, it underscores that status does not change how public-safety statutes are applied — even if it intensifies attention.

More broadly, it reflects a recurring reality of criminal law: the system often acts early and explains itself later.

Can someone be charged with deadly conduct if no one was hurt?

Yes. Texas law focuses on whether the alleged conduct created a substantial risk to others, not whether an injury occurred.

Does this mean Myles Jack is guilty?

No. Charges are allegations only. Guilt can be determined only through a plea or trial.

Why were nearby homes evacuated?

Evacuations are a standard police response when officers believe there is an unresolved firearm-related risk.

Could the charges change or be dropped?

Yes. Prosecutors can amend, reduce, or dismiss charges as evidence is reviewed.

Is posting bail the end of the case?

No. Bail allows temporary release while the case continues through the courts.

Editorial rule of thumb: when headlines focus on the arrest, Lawyer Monthly explains how the law actually works.

👉 Related: Why the Tyler Skaggs wrongful-death case against the LA Angels settled during jury deliberations 👈

Under California law, a wrongful-death lawsuit can legally settle at any point before a verdict is read into the court record—even if jurors are already deep into deliberations.

That procedural rule is what brought a sudden end to the civil case filed by the family of Tyler Skaggs against the Los Angeles Angels, stopping the trial just as jurors were nearing a decision. The settlement ends the case entirely, but it does not amount to a legal finding of fault or an admission of wrongdoing.

For readers watching from the outside, the timing can feel confusing—even suspicious. In reality, this is often the most predictable moment for a civil case to resolve.

A wrongful-death settlement during jury deliberations is a private legal agreement, not a court ruling. It replaces the uncertainty of a jury verdict with guaranteed compensation. No damages are “awarded,” no liability is formally decided, and no precedent is created.

By the time jurors began deliberating, the legal die was largely cast. Weeks of testimony were over. Experts had testified. Lawyers had delivered their closing arguments. The only thing left was a number—and who would be ordered to pay it.

At that point, both sides gained something they did not have before: clarity about risk.

Juror questions about damages, requests to review testimony, and the structure of verdict forms often signal how responsibility is likely to be divided and whether a substantial financial award is coming. Even without knowing the final vote, lawyers can usually tell when a case is tipping in one direction.

That is why so many civil cases—especially wrongful-death suits—settle late. It is not about panic. It is about certainty.

This was never a criminal trial. No one in this courtroom was being asked to decide guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Instead, jurors were working through a narrower civil framework under California law.

They were asked to determine whether the Angels were negligent in their supervision of a team employee, whether that negligence played a substantial role in Skaggs’ death, and how responsibility should be divided among multiple parties. Only after answering those questions would damages be calculated, including future earnings and emotional loss.

Those answers never became official, because the settlement froze the process before the verdict could be delivered.

It does guarantee compensation without appeal

It does end the lawsuit permanently

It does not legally assign fault

It does not reflect a court’s judgment

This distinction matters. Settlements are contracts, not conclusions.

When a wrongful-death case settles during deliberations, the dollar figure is rarely a shot in the dark. By this stage, both sides know the realistic range of outcomes.

Plaintiffs weigh the possibility that jurors could reduce damages, assign blame elsewhere, or return a defense verdict. Defendants face the risk of a massive award, punitive damages, and years of appeals. Insurance coverage limits, deductibles, and consent requirements often play a decisive role behind the scenes.

What emerges is usually a number that reflects what lawyers believe the jury was about to do—discounted slightly so everyone walks away without the risk of losing everything.

Once the judge is told a settlement has been reached, the courtroom process ends quickly. Jurors are dismissed, deliberations stop, and verdict forms are void. The judge does not weigh in on fault or damages. The court’s role becomes purely administrative.

From that moment on, the case exists only as a settlement agreement waiting to be finalized.

Payment does not arrive instantly, but the process is usually straightforward. First, the written settlement agreement is finalized and signed. Then insurers release funds, often within 30 to 60 days depending on policy terms.

Because wrongful-death claims involve multiple beneficiaries, courts typically review how the settlement is divided among surviving family members. Attorneys’ contingency fees and litigation costs are deducted before the remaining funds are distributed.

Only after those steps are completed does the family receive payment.

The civil case did not exist in a vacuum. It followed a long and painful sequence of events.

Skaggs died on July 1, 2019, during a team road trip after ingesting a fentanyl-laced pill. A federal investigation later led to the conviction of Eric Kay, a team employee who was sentenced to 22 years in prison. That criminal case established individual responsibility, but it did not resolve questions of organizational liability.

The wrongful-death lawsuit that followed took years—marked by discovery battles, expert testimony, and delays—before finally reaching trial. More than 30 days of testimony later, the jury began deliberating. Within days, the case was over.

This settlement does not rewrite history, undo a death, or answer every moral question surrounding the case. What it does is bring finality. No appeals. No retrials. No years of uncertainty.

That is why civil law allows settlements so late in the process. The system prioritizes resolution over spectacle.

For employers and organizations, the case is a reminder that civil exposure can extend long after criminal accountability is resolved. For families, it shows how leverage often peaks at the very end of trial. For insurers and defendants, it underscores a hard truth of litigation: the closer a jury gets to deciding damages, the more expensive uncertainty becomes.

Can a wrongful-death case really settle after jurors start deliberating?

Yes. Until a verdict is officially entered, settlement remains legally available.

Does settling mean the defendant admitted fault?

No. Civil settlements typically include no admission of liability.

Will the jury’s internal decision ever be made public?

No. Once jurors are dismissed, their deliberations have no legal standing.

Does this affect the criminal case?

No. Criminal convictions and civil settlements operate independently.

Is this common in high-stakes civil trials?

Very. Many of the largest settlements occur when verdicts are imminent.

Editorial rule of thumb: when the headlines stop at “they settled,” Lawyer Monthly explains what that actually means.