Who Was Edmond Safra? Inside the Monaco Death That Exposed a System Failure — and Why the Case Still Won’t Fully Close

When billionaire banker Edmond Safra died in his Monaco penthouse in the early hours of December 3, 1999, the initial explanation sounded straightforward: a fire, smoke inhalation, a tragic accident.

But almost immediately, the facts refused to align. Safra was one of the most security-conscious financiers on earth, living inside a residence engineered to withstand kidnappings and assassinations. And yet, he died not because help never arrived—but because help could not reach him in time.

More than twenty-five years later, renewed interest sparked by Netflix’s Murder in Monaco has brought the story back into public conversation. Much of the coverage focuses on Ted Maher, the nurse convicted of arson causing death. What’s still missing from most retellings is the larger truth: this case sits at the intersection of extreme security, institutional hesitation, and narrow legal framing—a convergence that turned a survivable emergency into a fatal one.

This article asks the questions many summaries don’t, answers what can be answered, and explains why the rest still matters.

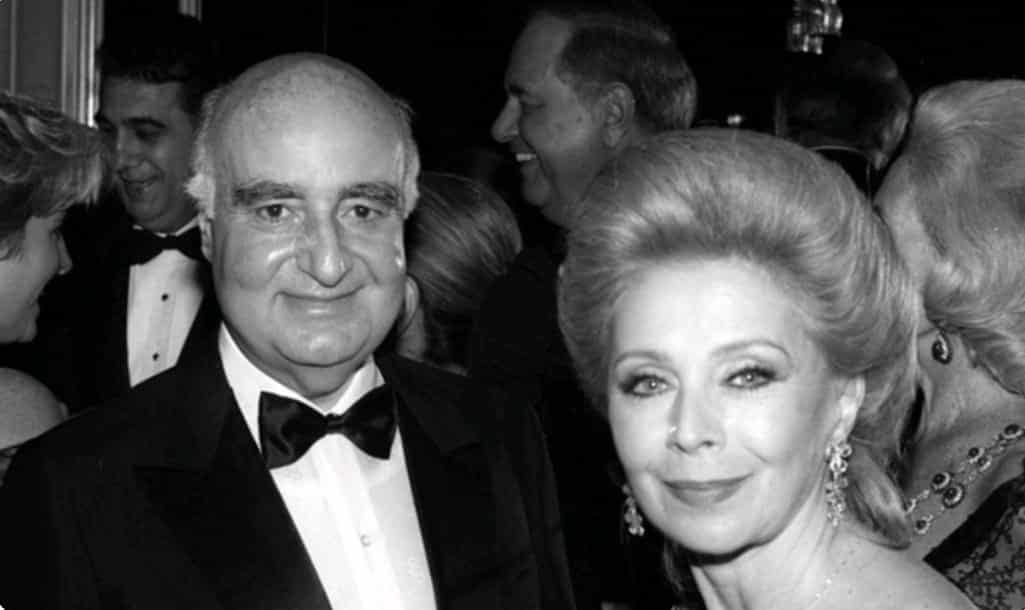

Edmond Safra: Power, Privacy, and the Cost of Absolute Security

Edmond Safra was born in Beirut on August 6, 1932, into a Sephardic Jewish banking family whose trading roots stretched back centuries. By his teens, he was immersed in finance; by his twenties, he was building banks across Europe and South America. Over decades, he founded and controlled institutions including Republic National Bank of New York and Trade Development Bank, becoming a trusted adviser to governments, institutions, and ultra-wealthy clients.

Safra’s wealth brought influence—and suspicion. For years, rumors circulated linking his banks to money laundering and organized crime. Courts later ruled those allegations defamatory or unsupported, but the reputational toll lingered. Safra responded by retreating further behind layers of protection. By the 1990s, his life was defined by privacy, ritual, and security protocols designed for worst-case scenarios.

As his Parkinson’s disease progressed, Safra required constant medical care. That necessity introduced private nurses into his most secure spaces—people vetted for clinical competence, not crisis management inside fortress-like residences.

Ted Maher: How an Outsider Entered the Inner Circle

Ted Maher’s life could not have been more different. Raised in upstate New York, he served as a medic with the U.S. Army’s Special Forces before training as a registered nurse. He worked in neonatal intensive care at Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital—skilled, disciplined, and far removed from the world of billionaires.

Through a chance connection involving Safra’s extended family, Maher was offered a lucrative position on Safra’s private nursing staff, earning more than $200,000 a year and splitting time between New York and Monaco. He spoke no French. He had no background navigating elite European security systems. He had been employed for months, not years, when the fire occurred.

That context matters, because it frames what happened next not just as a crime, but as a collision between human error and an unforgiving system.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(739x272:741x274):format(webp)/Ted-Maher-2002-121825-1093a52e2b06410793a4f5a7511874a8.jpg)

Ted Maher on December 2, 2002.

What Happened the Night Edmond Safra Died?

In the early morning hours of December 3, 1999, Maher reported that intruders had attacked him inside the penthouse. Safra and another nurse, Vivian Torrente, retreated into a steel-reinforced bathroom designed to function as a panic room. Elsewhere in the apartment, a fire began.

Police arrived quickly. Firefighters were dispatched. And then time slipped away.

The penthouse was protected by reinforced doors, layered alarms, and protocols meant to repel armed attackers. Responders treated the scene as a potential ongoing threat. Entry was delayed. Decisions were cautious and fragmented. The very features designed to keep Safra safe prevented rapid rescue.

When authorities finally breached the apartment hours later, Safra and Torrente had died from smoke inhalation.

Why the Case Turned on Ted Maher

Within days, Monaco authorities concluded there were no intruders. Investigators alleged Maher had staged the attack, injured himself, and started the fire to appear heroic and secure his job. Maher confessed, reenacted events, and was charged with arson causing death—a crime that does not require intent to kill under Monaco law.

In December 2002, he was convicted and sentenced to ten years in prison.

Legally, the case was resolved. Historically—and morally—it was not.

A Comprehensive Timeline of the Safra Case

-

Aug. 6, 1932 — Edmond Safra is born in Beirut, Lebanon.

-

1947 — At age 15, Safra is sent to Milan, where he begins gold and currency trading.

-

1954 — Safra relocates to Brazil, expanding banking operations in South America.

-

1966 — Safra founds Trade Development Bank in Geneva.

-

1970s–1980s — Safra becomes a dominant figure in global private banking.

-

1983–1988 — Corporate disputes and reputational battles shape Safra’s security posture.

-

1990s — Safra intensifies personal security amid rumors and legal scrutiny.

-

Late 1990s — Safra’s Parkinson’s disease progresses; private nursing care becomes essential.

-

Summer 1999 — Ted Maher joins Safra’s nursing staff in Monaco.

-

Dec. 3, 1999 (early morning) — Fire breaks out in Safra’s Monaco penthouse; Safra and Vivian Torrente retreat to a panic room.

-

Dec. 3, 1999 (hours later) — Firefighters breach the residence; Safra and Torrente are found dead from smoke inhalation.

-

Dec. 6, 1999 — Monaco police announce Maher’s confession narrative.

-

Oct. 29, 2000 — The Guardian publishes a major investigative feature highlighting inconsistencies and unanswered questions.

-

Dec. 2002 — Maher is convicted of arson causing death and sentenced to ten years.

-

Jan. 2003 — Maher attempts to escape custody and is quickly recaptured.

-

Oct. 2007 — Maher is released from prison.

-

March 2008 — Maher recants elements of his confession in U.S. media interviews, alleging coercion.

-

2013 — Maher’s nursing license is revoked in Texas.

-

2022–2023 — Maher (now using the name Jon Green) is convicted of forgery-related crimes in the U.S.

-

March 2025 — Maher is found guilty in a murder-for-hire case.

-

July 2025 — He is sentenced to an additional nine years in prison.

-

Dec. 17, 2025 — Netflix releases Murder in Monaco, reigniting public scrutiny.

The Institutional Failure Most Coverage Avoids

The most revealing aspect of Safra’s death is not who was convicted, but what was never fully examined.

Safra’s penthouse was so secure that emergency responders could not act decisively. Police treated the scene as an active threat rather than a rescue. Firefighters waited for authorization. No single authority assumed command. Each delay compounded the danger.

The panic room—a space designed to isolate Safra from harm—became a sealed chamber of smoke. Its purpose worked against him once fire entered the equation.

By focusing narrowly on Maher’s act of starting the fire, the legal process avoided confronting a harder truth: even reckless behavior does not have to be fatal if systems function properly. No institution—police, fire services, building security—faced criminal scrutiny. No systemic reforms followed.

The Questions That Still Demand Answers

Despite a conviction, unresolved issues remain central to understanding the case. Investigators reportedly identified more than one fire origin. Early accounts conflicted on whether Safra communicated with his wife or security while trapped. Security recordings were described as unavailable or nonfunctional. And it remains unclear why it took hours to breach a bathroom in one of the most heavily policed places on Earth.

These questions do not overturn the verdict. They explain why doubt persists.

Where Ted Maher Is Now—and Why It Matters Less Than You Think

After his release in 2007, Maher returned to the United States, changed his name to Jon Green, lost his nursing license, and was later convicted of additional crimes, including murder-for-hire. In July 2025, he received an additional nine-year sentence and is currently incarcerated in New Mexico, reportedly suffering from late-stage throat cancer.

His later crimes harden public perception—but they do not retroactively explain what happened in Monaco.

So What Really Killed Edmond Safra?

Legally, Edmond Safra died because of arson causing death. Practically, he died because smoke filled a room rescuers could not reach. Historically, his death represents something more complex: a moment when fear, secrecy, and over-securitization combined with institutional hesitation to produce a fatal outcome.

Safra did not die because help never came.

He died because help could not reach him in time.

That distinction—uncomfortable and unresolved—is why this case still matters, and why it continues to rank among the most baffling deaths in modern financial history.