Arizona Police Use AI to Improve Suspect Composite Images

Goodyear police are piloting AI-enhanced suspect composites, raising new questions about identification accuracy, public alerts and how digital images will be treated in criminal cases.

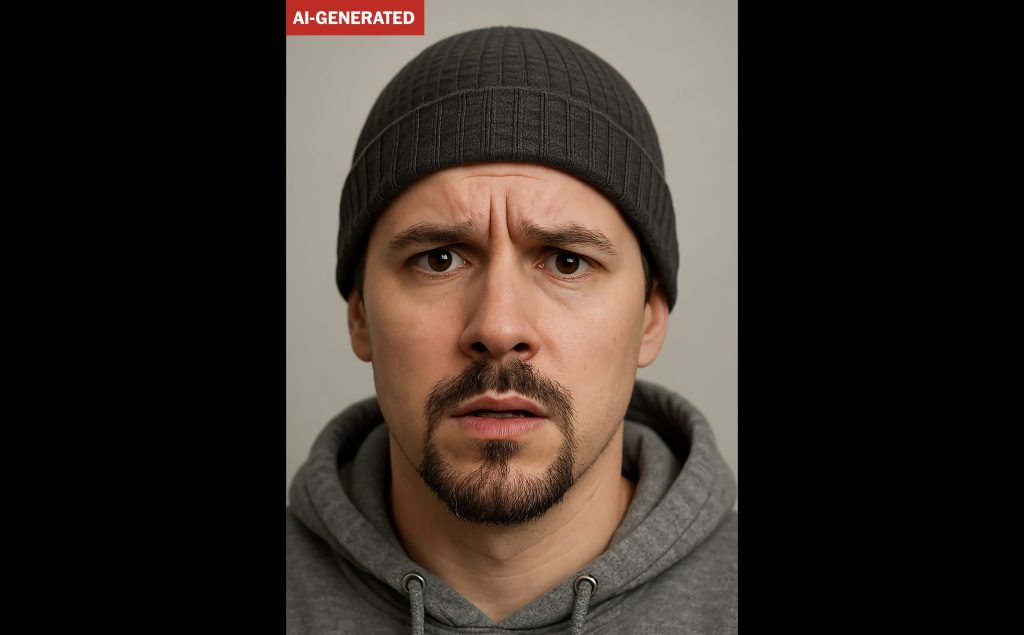

Two days after a late-November shooting in Goodyear, a fast-growing suburb of Phoenix, police asked residents for help identifying a man shown in what looked like a mug shot: a middle-aged figure in a hoodie and beanie, with a short goatee and blank expression.

The department stressed that the picture was not a real photograph but an AI-generated image built from a witness interview and a traditional hand sketch.

The approach follows an earlier April 2025 case, when Goodyear first released an AI composite for an attempted kidnapping of a 14-year-old girl.

The shift matters because image-based identification is already under scrutiny in U.S. courts and legislatures, especially as police adopt facial recognition and other automated tools.

Federal agencies and major AI companies have agreed to voluntary commitments encouraging watermarking and clear labelling of AI-generated content, while the Biden administration’s 2023 executive order on AI presses for transparency and safeguards around high-risk systems.

These developments form the backdrop for experiments like Goodyear’s, where lifelike AI faces may influence what witnesses, jurors and members of the public think they are seeing.

How Goodyear’s AI composite system works in practice

Goodyear’s process still begins with a standard investigative interview. A trained forensic artist speaks with victims and witnesses, asking structured questions about facial shape, hair, age range and other features, in line with long-standing composite sketch protocols.

The artist first produces a pencil sketch, then uses an AI tool to convert that drawing into a photorealistic face, iterating on the image while the witness watches and suggests adjustments.

The April 2025 AI image, released after the attempted abduction of a 14-year-old on 144th Avenue, shows a white man believed to be between 50 and 60 years old, around six feet tall and about 200 pounds, with blue eyes and brown hair.

Officials say the same workflow was used in November’s shooting case, with a witness repeatedly describing the suspect’s “dumbfounded” look, which the artist then asked the AI system to convey.

Both AI-assisted cases remain open, and police say neither image has yet produced an arrest. However, the department reports that its first AI composite generated a noticeably larger volume of public tips than earlier hand-drawn sketches.

How officials and communities are reacting

Goodyear’s forensic artist, Officer Mike Bonasera, has publicly endorsed the AI tool as a way to modernise suspect appeals and capture public attention on social media feeds that are saturated with high-resolution imagery.

He has sketched suspects for about five years and now says he plans to use AI for all future composites after securing sign-off from department leadership and the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office.

Elsewhere, law-enforcement use of AI images has already triggered backlash. In July 2025, the Westbrook Police Department in Maine apologised after posting an image of seized drugs that turned out to be an AI-generated fabrication.

An officer had used ChatGPT to add a department badge to a real evidence photo; the tool instead produced a fully synthetic picture, which the agency mistakenly shared and initially defended as genuine before acknowledging the error.

Civil-rights and technology advocates have warned that highly realistic AI imagery can be misleading if not clearly labelled.

National and international guidance has increasingly pushed for transparency: the White House’s 2023 voluntary AI commitments and subsequent executive order both highlight watermarking and disclosure for AI-generated content as a basic safeguard.

What AI suspect images mean for public identification

For members of the public, AI-generated composites may feel more “real” than traditional sketches, even though both are rooted in the same fallible human memory.

Research on facial composites has long shown that people often struggle to match or correctly name a suspect from a sketch, with recognition rates in some studies hovering around 20 percent for modern composite systems.

At the same time, facial-recognition benchmarks from the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have documented persistent accuracy gaps across demographic groups, with some algorithms misidentifying Black and Asian faces more frequently than white faces.

If an AI composite were later fed into such systems without safeguards, those combined weaknesses could amplify the risk of mistaken identity.

A 2019 campaign and technical review by Georgetown Law’s Center on Privacy & Technology advised agencies not to submit artist sketches to face-recognition databases at all, warning that sketches are “highly unlikely” to produce a correct match and may generate misleading candidate lists.

That concern remains relevant when the “sketch” is AI-enhanced and appears closer to a candid photograph.

Research evidence on composites, memory and AI tools

Decades of cognitive-psychology research show that human memory for faces degrades quickly and can be reshaped by later information.

Meta-analyses of composite systems such as E-FIT, PROfit and EvoFIT have repeatedly found that correct naming rates are low and can drop further when there is a long delay between seeing the face and constructing the composite.

A comprehensive 2020 review in Criminal Justice and Behavior concluded that viewing facial composites can even distort a witness’s later memory, sometimes pulling recollection toward the composite rather than the original face.

Separate studies comparing professional facial examiners, “super-recognisers” and algorithms find that top-tier algorithms can now match trained experts on high-quality images—but those tests typically use real photographs, not sketches or AI renditions.

Legal scholars, including those at the University of Arizona and George Washington University, have highlighted a procedural gap: a forensic artist can explain their choices under oath, but the internal workings of a large generative model are far harder to interrogate in court.

How residents can respond and report information

Goodyear officials say AI composites are used solely to request leads. Under Arizona’s public-records law, A.R.S. § 39-121, residents have a general right to inspect existing public records, though active investigative materials can be withheld in some circumstances.

Anyone who believes they recognise a person from an AI composite is urged not to confront individuals directly. Instead, Goodyear’s official guidance is to report crimes in progress via 911 and use the 24-hour non-emergency line — 623-932-1220 — for tips about past incidents or possible suspects.

The department also offers online reporting for certain non-violent offences via its city website.

Residents who want to understand how their information will be handled can consult local public-records policies or ask to speak with a case detective before sharing detailed statements.

Next steps for Goodyear and other agencies

Goodyear police say they intend to keep using AI to enhance suspect sketches in future cases, now that the process has internal approval and has produced a larger volume of public tips.

Investigators will continue to treat the images as one tool among many, alongside witness interviews, physical evidence and any available surveillance footage.

Professionally, Bonasera has begun sharing his workflow with other departments, and law-enforcement trade outlets have covered Goodyear’s approach in detail, which could encourage pilot projects elsewhere.

Any broader rollout is likely to be shaped by future case law, state-level AI policies and internal guidelines on how and when such composites may be entered into evidence.

Why this story matters for public identification and policing

This development highlights how a long-standing investigative tool, the witness-based composite sketch is being adapted with new digital methods.

It affects residents who may encounter these images in public alerts, witnesses whose descriptions are translated into visual form, and individuals whose likeness may be approximated without a photograph.

The approach raises practical questions about accuracy, fairness and how memory-based images should be presented and interpreted.

As more agencies examine similar tools, clear explanation, proper labelling and transparent rules on how these images are used in investigations will be essential for maintaining public confidence.