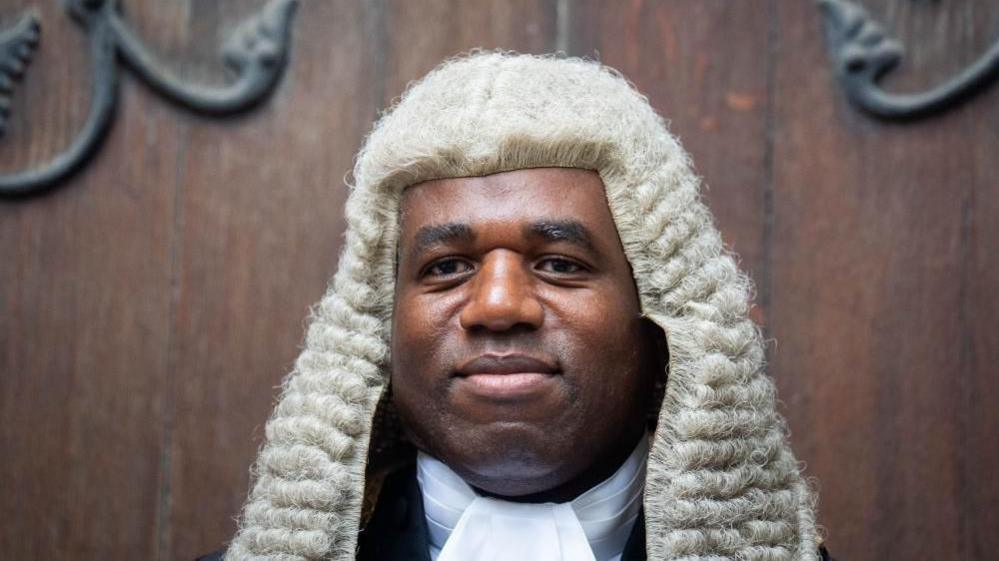

David Lammy’s Jury Trial Reform Plan: What Judge-Only Cases Could Mean for UK Justice

A leaked Ministry of Justice memo has revealed plans to shift most criminal cases carrying potential sentences of up to five years from jury trials to judge-only hearings. The proposal—now reportedly being scaled back following intense political and legal backlash—aims to reduce the severe Crown Court backlog but has drawn scrutiny because it would significantly curtail the long-standing role of juries in England and Wales.

Policy Breaking News

The Government was thrown into chaos this week after a confidential Ministry of Justice briefing revealed that Justice Secretary David Lammy had approved proposals to remove jury trials from the overwhelming majority of Crown Court cases. The plan, which surfaced only 48 hours ago, outlined a major structural reform: criminal cases with a possible sentence of up to five years would be decided by a judge sitting alone, with juries reserved only for the most serious offences.

The leak triggered immediate uproar across Parliament, the judiciary and the criminal bar. Senior MPs accused the Government of “constitutional vandalism,” while legal commentators warned that shifting up to 95% of trials to judge-only hearings would fundamentally alter the balance of public participation in justice.

Amid the backlash, new reports now suggest ministers are preparing to scale back the reforms, signalling uncertainty at the heart of government policy. For lawyers, defendants, victims and court administrators, the stakes are high: the proposals are designed to tackle a backlog exceeding 78,000 Crown Court cases, yet may reshape centuries of jury tradition.

What the Law / Bill / Rule Actually Does

The leaked policy document proposes:

-

A new Crown Court Bench Division (CCBD) to hear cases usually attracting sentences of up to five years.

-

Judge-only trials for the majority of non-fatal, non-sexual offences currently tried before juries.

-

Retention of juries for murder, rape, manslaughter and a narrow set of “public interest” cases.

-

A new allocation system, under which judges would triage incoming cases and determine whether jury trial is necessary.

If implemented, this would mean:

-

Most Crown Court cases currently waiting for trial would no longer be sent to juries.

-

Only the most serious cases would remain in the traditional Crown Court structure.

-

Enforcement would fall under new procedural rules and potentially a primary Act of Parliament.

The reforms represent a significant departure from current law, where juries hear serious indictable offences unless a defendant elects otherwise or the case is transferred downward.

Why the Policy Was Introduced

The Government argues the proposals are a response to:

-

A record Crown Court backlog, with tens of thousands of cases delayed for years.

-

Victims withdrawing, particularly in sexual offence cases where long delays lead to emotional and evidential collapse.

-

Concerns about system capacity, following years of courtroom closures, judicial shortages and underfunded legal aid.

-

A belief that judge-only trials could deliver faster, more predictable outcomes.

Officials also referenced earlier recommendations from senior judicial figures calling for structural reform to prevent the criminal courts from reaching crisis point.

However, critics argue the reforms address symptoms, not causes — and that jury trials are not the reason delays exist.

Legal Framework + What the Law Means

The proposal fits within the realm of criminal procedure and administrative law, where Parliament is free to determine how serious offences are tried, provided fair-trial rights remain intact.

Key points:

-

Jury trials are not constitutionally guaranteed in the UK, though they hold deep historical weight.

-

Article 6 of the ECHR allows judge-only trials if they are fair, independent and proportionate.

-

Courts typically examine whether a defendant retains:

-

access to evidence,

-

the right to challenge witnesses,

-

an impartial tribunal,

-

and appeal rights.

-

-

Similar judge-only models exist internationally, especially for fraud and technical cases.

If passed, the reforms would create a dual-tier system requiring new compliance protocols, judicial training and clear allocation rules to avoid arbitrary decision-making.

Impact on Businesses

For law firms, insurers and litigation-support companies, the reforms would reshape:

-

Case strategy — less emphasis on narrative persuasion, more on legal and evidential precision.

-

Workflows — earlier document review, tighter case preparation and increased reliance on expert evidence.

-

Budgets — potentially shorter hearings but heavier front-loading of work.

Corporate defendants in fraud or regulatory matters may face faster trial dates, altering settlement and risk-management strategies.

A new judge-only system would also increase scrutiny on judicial decision-making, with appeal routes expected to become more active and more closely monitored.

Impact on Consumers

For the public, the consequences are far-reaching:

-

Fewer opportunities for jury service, reducing direct civic engagement in criminal justice.

-

Faster case resolution, which could help victims gain closure sooner.

-

Concerns about fairness, particularly for defendants from under-represented communities who may trust juries more than judicial decision-makers.

-

Debate over discrimination, given research suggesting juries tend to show less racial bias than other parts of the system.

For victims, defendants and witnesses, the question is whether speed should prevail over tradition and perceived legitimacy.

Key Questions About the Bill / Policy

Can businesses or defendants still request a jury trial?

Under the leaked proposals, the default for mid-level offences would be judge-only. Only the most serious cases would retain automatic juries unless Parliament inserts a right to request one.

Does this conflict with constitutional principles?

The UK does not have a constitutional right to a jury, but jury trials are a long-standing safeguard. Any reform must still satisfy fair-trial standards and be proportionate to the crisis it aims to solve.

Will fraud and financial crime be included?

Yes. Technical cases such as complex fraud are among those likely to move to judge-only hearings, a change some judges have previously supported for efficiency.

Could this increase appeals?

Possibly. Concentrating decision-making in a single judge may produce more appeal challenges, especially on findings of fact.

Does this affect all UK jurisdictions?

No. The proposals apply only to England and Wales, not Scotland or Northern Ireland.

What Happens Next in the Legislative / Regulatory Process

The Ministry of Justice says no final decision has been taken. The expected next steps include:

-

internal Whitehall negotiations,

-

potential announcement of a scaled-down proposal,

-

publication of a policy paper or draft Bill,

-

committee scrutiny in both Houses,

-

formal Parliamentary debate and possible amendments,

-

development of procedures for judicial allocation and appeals,

-

phased implementation if legislation passes.

Given the political backlash, significant revisions are likely before any Bill is introduced.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is this an emergency measure?

No. Any reform would require legislation, meaning it would become a permanent structural change unless later repealed.

Are juries being abolished?

No, but their role would be sharply reduced. Jury service would remain only for the most serious offences.

What prompted the backlash?

Lawyers, judges and MPs argue that removing juries risks miscarriages of justice and undermines public trust in criminal verdicts.

Does this reduce discrimination?

Some MPs argue the opposite, noting that juries have historically shown lower levels of racial bias than other justice processes.

Final Legal Takeaway

David Lammy’s leaked jury-trial reforms mark one of the most consequential modern debates on how criminal justice should function in England and Wales. They aim to solve a severe backlog but raise fundamental questions about fairness, tradition and public legitimacy. The proposals affect defendants, victims, legal practitioners and the wider public, and any enacted version would permanently reshape criminal procedure.

The Government is already reconsidering the scope of its plan, but the direction of travel is clear: the balance between efficiency and public participation is being renegotiated. What Parliament decides next will determine whether the UK’s 800-year-old jury tradition remains central to justice or evolves into a narrower, more symbolic role.

👉 When Countries Say No: The Legal Grounds That Let Nations Reject Extradition Requests 👈