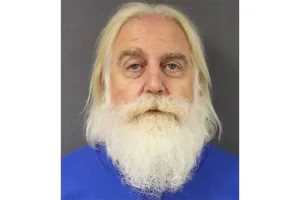

Former Deputy Police Commissioner Jevon McSkimming’s criminal charges for accessing illegal sexual images on police devices illustrate how misconduct at senior levels can trigger broader questions about internal safeguards and the legal standards that apply when law enforcement personnel are accused of criminal wrongdoing. Once allegations reach this rank, the law shifts from focusing solely on individual behaviour to evaluating the mechanisms designed to ensure accountability.

What the Charges Mean

Charges involving the possession or viewing of child sexual abuse material fall under some of the most serious provisions in New Zealand’s Crimes Act. These offences are assessed through factors such as the type of material, the frequency of access, and the use of government systems. Courts typically consider:

-

the quantity and nature of the material

-

the context in which the images were accessed

-

whether workplace systems were involved

-

the defendant’s position of responsibility

For any law enforcement officer, and especially for one in a senior role, breach of trust can be viewed as an aggravating feature during sentencing.

How Internal Misconduct Investigations Normally Work

Misconduct processes in policing rely on structured reporting channels. When allegations involve senior officials, those processes must account for conflicts of interest. A standard pathway includes:

-

Receipt and recording of the complaint

-

Initial assessment for independence concerns

-

Preservation and examination of digital evidence

-

Parallel administrative and criminal reviews, each with different evidentiary thresholds

Where the accused holds authority over those conducting the inquiry, oversight bodies such as the Independent Police Conduct Authority (IPCA) often play a role to reinforce process integrity.

Power Imbalances and Public Misunderstandings

When an accused individual holds institutional authority, public confusion often centres on what “abuse of power” means under the law. New Zealand law does not treat power imbalance as a standalone criminal offence. Instead, it influences several downstream assessments, including:

-

how investigators weigh the circumstances of a complaint

-

whether any workplace dynamics affect credibility evaluations

-

whether impartiality in the process needs extra scrutiny

These considerations guide the process, not the determination of criminal guilt itself, and they help ensure assessments are grounded in verifiable evidence.

How Digital Evidence Is Evaluated

Investigations involving illegal images typically rely on detailed forensic analysis of digital devices. Examiners review:

-

search history and timestamps

-

cached or temporary files

-

login and access logs

-

metadata linking content to specific accounts

-

chain-of-custody documentation for seized devices

A common misconception is that streaming imagery avoids liability. In New Zealand, knowingly accessing illegal sexual images can be an offence regardless of whether the material is stored or downloaded, provided investigators can show intentional viewing.

Read: 👉 Curious About Forensics? Here’s What Experts Want You to Know Before You Dive In 👈

Oversight and Investigations Involving Senior Officials

Oversight bodies intervene when allegations involve people with significant organisational influence. Their involvement centres on whether:

-

standard procedures were followed

-

investigators had the independence required for impartial analysis

-

any deviations from protocol require review or correction

This external scrutiny is intended to reinforce public confidence and ensure that seniority does not affect investigative decisions.

What Happens After an Admission of Charges

Following a guilty plea to offences involving illegal sexual images, the case moves directly toward sentencing. Judges consider statutory maximums, the specifics of the offending, and recognised mitigating or aggravating factors.

Separate from the criminal process, law enforcement officers typically face employment consequences, removal of access privileges, and restrictions resulting from internal policy requirements. These administrative outcomes proceed under their own rules and are independent of the court’s decision.

Common Misconceptions in Cases Involving Police Personnel

Myth 1: A complaint must be “proven” before police can investigate.

Investigations begin when credible information is provided; proof applies later, under courtroom standards.

Myth 2: If certain allegations are not prosecuted, they were dismissed as unfounded.

Prosecution decisions turn on available evidence and the ability to meet the “beyond reasonable doubt” standard for each charge.

Myth 3: Police always investigate misconduct internally.

Serious allegations—especially involving senior roles—are often reviewed or overseen by independent bodies to maintain impartiality.

As the case moves toward sentencing, the legal system’s attention shifts to the structural safeguards surrounding high-ranking officials. Cases involving senior police figures often prompt renewed discussion about oversight, internal controls, and the practical steps institutions must take to ensure that investigative processes operate independently of hierarchy.

Frequently Asked Legal Questions About the McSkimming Case

What is the maximum penalty for accessing illegal sexual images in New Zealand?

The Crimes Act permits penalties of up to 10 years’ imprisonment, depending on the circumstances and severity of the material.

Can workplace computer activity be used in court?

Yes. Activity on government devices is routinely logged and can be preserved for forensic analysis.

Who provides external oversight in police misconduct cases?

The Independent Police Conduct Authority (IPCA) reviews or oversees cases involving potential conflicts of interest or serious allegations.

Do criminal and employment investigations run together?

They can. Internal employment processes follow separate standards and timelines and do not depend on the outcome of criminal proceedings.