Can Lily Allen Be Sued for Her Lyrics? Defining the Legal Boundaries of Art

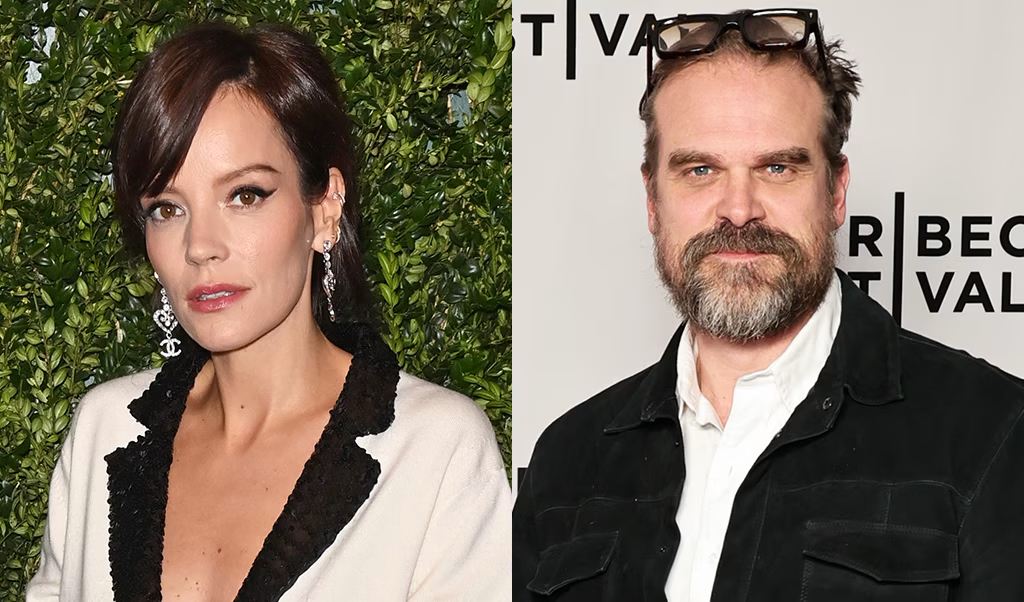

After months of speculation and whispered clues hidden in Lily Allen’s explosive new album West End Girl, actor David Harbour has finally spoken out.

In a rare interview with Esquire Spain, the Stranger Things star opened up about turning 50, reflecting on heartbreak, mistakes, and the search for redemption following his split from Allen — whose latest record lays bare a marriage that once looked golden from the outside.

“You either accept your path completely,” Harbour said quietly, “and realize that even the pain, the slip-ups, and the mistakes are all part of the journey. There’s growth and empathy in all that.”

It was a strikingly self-aware confession from an actor more often seen wielding sarcasm and a sheriff’s badge. Yet the timing was no accident. Allen’s album — written in just 10 days after their separation — paints a vivid picture of betrayal, secrecy, and emotional exhaustion.

Through tracks like “Tennis” and “Madeline,” she channels raw anger and disbelief: “You won’t play with me — who the f** is Madeline?”*

The Album That Shook Pop Culture

Fans have called West End Girl the British Lemonade — a reference to Beyoncé’s 2016 confessional masterpiece. But Allen’s lyrics go further, detailing late-night texts, double lives, and one name that’s become its own cultural riddle: Madeline.

When Allen appeared at a Halloween party dressed as the children’s-book character Madeline, the internet erupted. “We got Jolene, Becky with the good hair, and now Madeline,” one fan joked on X.

Speculation grew that the mysterious Madeline wasn’t real but a pseudonym created for legal protection, allowing Allen to tell her story without identifying anyone directly. Her label declined to comment — a silence that said plenty.

Harbour, meanwhile, didn’t mention the album directly but admitted to “regret and deep learning.” Looking ahead, he said there are still people he wants “to love, to be good to, and to nurture.”

Related Exclusive: Stranger Things Scandal

Legal Spotlight: Can Lily Allen Be Sued for Her Lyrics? What UK Law Says About Turning Private Pain Into Art

Whenever a public breakup becomes the subject of a chart-topping record, one question inevitably follows: Can you be sued for what you sing?

Under UK defamation law, a person may sue if a publication — including a song — damages their reputation by making false claims. To win, the claimant must prove that:

-

The words are about them;

-

The words were published to others; and

-

The content caused serious harm.

But here’s the legal twist: truth is a complete defense. If Allen’s lyrics reflect events that genuinely happened — even if painful or unflattering — she’s shielded from liability. UK courts also protect freedom of artistic expression under Article 10 of the Human Rights Act 1998, granting wide creative latitude to musicians and writers.

The “Madeline Clause” — How Artists Protect Themselves

In today’s music industry, it’s common to disguise real identities behind composite characters or pseudonyms — informally dubbed the Madeline Clause. By fictionalizing names and altering details, artists can explore personal experiences without directly identifying anyone. Labels often run every lyric through legal review before release, especially in albums based on real relationships.

So What Does This Mean for You?

Even ordinary people posting about relationships online face similar rules. You can share your truth, but accuracy and respect for privacy matter. If you blog, post, or write music about a breakup, avoid publishing identifiable details that could harm someone’s reputation. Stick to your own experience — not unverified accusations — and your story remains legally protected self-expression.

Expert Takeaway:

In Allen’s case, the decision to rename her alleged rival Madeline was likely a deliberate legal safeguard. It lets her vent emotional truth while protecting both her label and herself from a potential defamation claim. Harbour could theoretically challenge specific lyrics, but doing so would require proving both falsity and measurable reputational damage — a steep uphill climb in creative works.

According to Tom Double, a media and communications lawyer at Brett Wilson LLP, “under the Defamation Act 2013, a claimant must show that the words complained of were published to a third party, referred to the claimant (directly or by inference), carried a meaning which would lower the claimant in the estimation of right-thinking members of society, and caused or are likely to cause serious harm to the claimant’s reputation. For a body that trades for profit, that means serious financial loss.”

The Bigger Picture

What began as a breakup ballad has ignited a broader conversation about truth, privacy, and the limits of public storytelling. Lily Allen’s record may chronicle heartbreak, but it also exposes the modern tension between artistic freedom and personal boundaries — a space where law, love, and pop culture collide.

As Harbour looks ahead to “being good to people” and Allen basks in newfound critical acclaim, one truth remains: in the court of public opinion, the lines between confession and creation have never been more blurred.

Lily Allen Madeline People Also Ask

Who is Lily Allen’s “Madeline”?

The identity of Madeline has not been confirmed. Most observers believe it’s a pseudonym used for privacy and legal protection under UK defamation law.

Could David Harbour sue Lily Allen over her lyrics?

Technically yes — but success would be unlikely. Truth and artistic expression provide strong legal defenses, especially in music and creative storytelling.

What is Lily Allen’s album West End Girl about?

The album chronicles Allen’s marriage breakdown and emotional recovery, using metaphor and character storytelling to explore love, betrayal, and self-rediscovery.

Final Takeaway:

The David Harbour–Lily Allen saga is more than celebrity gossip — it’s a modern case study in how far truth can travel when filtered through art. For anyone watching their favorite stars navigate heartbreak in public, one thing’s clear: behind every lyric and lawsuit lies the same fragile question — how much of your own story is truly yours to tell?