I Was Told to Say Sorry": Florida Lawsuit Tests Qualified Immunity After Child Forced to Apologize to Her Rapist

A Child’s Apology That Became a Constitutional Question

When a Florida teenager was forced to apologise to the man who raped her, it didn’t just expose investigative failure — it triggered a constitutional firestorm.

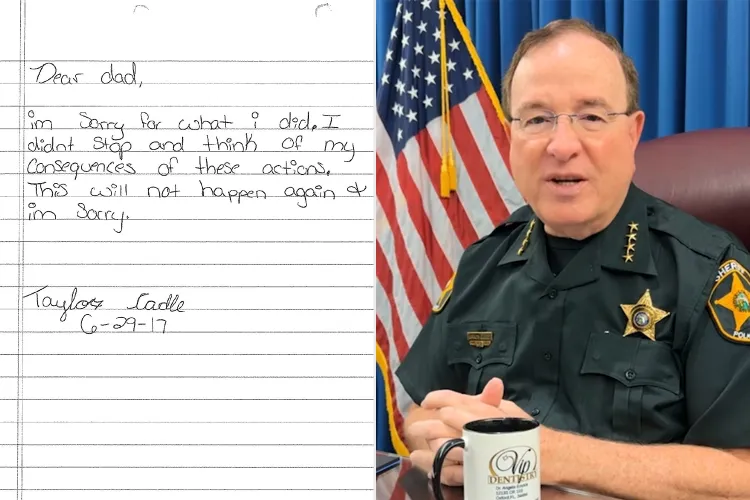

Taylor Cadle, now 22, has named Sheriff Grady Judd and investigator Melissa Turnage in a federal civil-rights suit, alleging that deputies coerced her—while a minor—to write apology letters to her abuser and to law enforcement, thereby violating her Fourteenth Amendment due-process rights and pushing past the shield of qualified immunity.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(742x162:744x164):format(webp)/letter-grady-judd-complaint-102425-98075bea1e9a4d5a940f83a0412501df.jpg)

Letters by Taylor Cadle. Credit: State of Florida

Evidence and Alleged Misconduct

Her complaint centres on two handwritten notes filed as exhibits:

-

“Dear Dad, I’m sorry for what I did. I didn’t stop and think of my consequences.” (addressed to her adoptive father)

-

“I know what I did wasn’t right; therefore I face my consequences.” (addressed to a law-enforcement officer)

The suit claims these were not voluntary but were dictated by deputies to justify terminating the original abuse investigation. Taylor was later returned to her father’s home, where she secretly captured further abuse on video — evidence that led to Henry Cadle’s conviction for sexual battery of a child by a custodian under Florida Statutes.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(731x205:733x207):format(webp)/letter-grady-judd-complaint-3-102425-e89b486264b04fefb01f89e8e573756d.jpg)

Letters by Taylor Cadle. Credit: State of Florida

Legal Foundation: Due Process, Qualified Immunity & State-Created Danger Doctrine

Taylor’s cause of action is grounded in 42 U.S.C. § 1983, which permits individuals to sue state actors for constitutional rights violations. Her legal team argues that forcing a minor to retract truthful abuse claims and apologise to her abuser constitutes affirmative misconduct under the state-created danger doctrine.

Under this doctrine, liability can attach when state actors increase a victim’s risk of harm through affirmative acts — not merely by failing to act. The suit distinguishes itself from DeShaney v. Winnebago County (1989), which addressed omissions rather than coercive acts. Because this case arises in the Eleventh Circuit, where qualified-immunity precedent is tightly maintained, a successful claim could significantly narrow immunity protections in future child-victim investigations.

David S. Weinstein, a former federal prosecutor and now a criminal defense attorney with Jones Walker LLP in Miami, told Lawyer Monthly:

“If these allegations hold, they present a textbook challenge to qualified immunity. Forcing a victim to recant under official authority goes beyond negligence — it’s an act that could clearly violate established due-process rights.”

Claims and Relief Sought

Taylor seeks compensatory, punitive and special damages, along with attorney’s fees and costs. The complaint alleges that the Polk County Sheriff’s Office failed to train investigators in child-abuse interview protocols and trauma-informed questioning.

In response, the sheriff’s office described the lawsuit as “a publicity stunt,” declaring that deputies “acted deliberately and rationally based on available evidence.”

Jurisdictional and Policy Impact

If the case survives early motions, it could set a fact-pattern precedent in the Middle District of Florida (Eleventh Circuit) for when coercive police conduct voids qualified immunity. Beyond the courtroom, advocacy groups are calling for federal training mandates and independent oversight of child-victim interviews. Florida’s Department of Law Enforcement is reportedly reviewing internal guidelines in light of the case.

Human and Ethical Dimensions

For Taylor Cadle, the apology letter remains a stark symbol of betrayal by those who should have protected her.

“I was a child who needed protection… instead, I was told to say sorry to the man who hurt me.”

Her case raises a core question: Can law-enforcement authority ever excuse moral failure when the victim is a child?

Key Legal Questions About the Florida Sheriff Lawsuit

Q1: Can officers lose qualified immunity for coercing a victim’s statement?

A: Yes. If a court finds the coercion violated clearly established constitutional rights—such as due process under the Fourteenth Amendment—the shield of qualified immunity falls away. The Cadle case could clarify this boundary within the Eleventh Circuit and shape how child-victim investigations are handled nationwide.

Q2: What is the state-created danger doctrine?

A: It’s a legal principle allowing victims to sue when government officials increase the risk of harm through their actions. In Taylor Cadle’s case, forcing her to recant and apologise could meet that threshold, distinguishing it from mere inaction.

Q3: Why is the Florida lawsuit significant for other states?

A: Because the Eleventh Circuit’s interpretation of qualified immunity covers Florida, Georgia, and Alabama. A ruling here could influence how future police-misconduct and child-protection cases are prosecuted across the South.