Swiss prosecutors have launched proceedings against an Australian racing driver accused of raping one of Michael Schumacher’s private nurses inside the Formula 1 champion’s Lake Geneva residence.

The alleged assault took place in November 2019 following a private cocktail gathering at the Schumacher family estate in Gland, Switzerland.

The suspect reportedly a close associate of Schumacher’s son, Mick, has since become unreachable, prompting international attention to the case’s jurisdictional and procedural complexities.

The proceedings have drawn significant scrutiny within legal circles, raising questions about international criminal jurisdiction, cross-border extradition, and victims’ rights under Swiss sexual-assault legislation.

Swiss prosecutors from the District of La Côte are asserting full jurisdiction, as the alleged offence occurred on Swiss territory.

Yet the accused’s Australian nationality complicates the matter, setting up a potential test case in international criminal liability and how nations cooperate when justice crosses borders.

International criminal jurisdiction refers to the power of a country or court to investigate and prosecute crimes that involve more than one nation, for example, when the accused and the crime are in different countries.

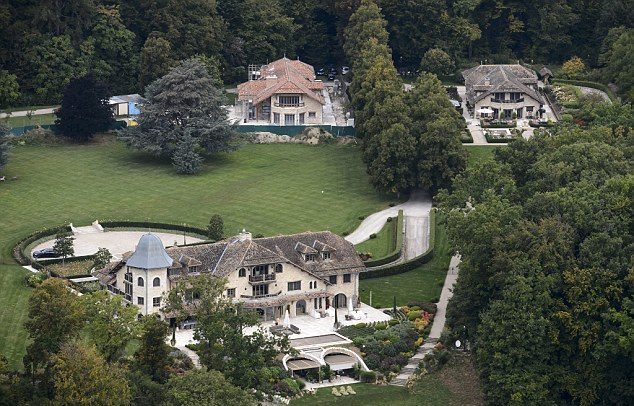

An aerial photograph of Michael Schumacher’s private estate in Gland, Switzerland, where prosecutors allege the assault took place in 2019.

It decides which country’s laws apply and who has the right to put a suspect on trial when the case spans borders.

In this instance, Switzerland claims authority because the alleged rape happened on its soil, while Australia could become involved if extradition or mutual legal assistance is required.

The alleged assault happened within the Schumacher estate, one of Europe’s most private residences.

Although the family is not implicated, legal experts say the event highlights the duty of care employers owe to medical staff working inside private homes.

If investigators determine that inadequate security measures allowed unsupervised guest access to staff areas during the cocktail event, potential civil liability could follow.

Such claims would not depend on direct fault but on whether the environment was reasonably safe for staff members.

According to prosecutors, the nurse reportedly in her 30s, became too intoxicated to stand after drinking vodka following a long shift.

She was later carried to a room and allegedly raped twice while unconscious.

Under Article 190 of the Swiss Criminal Code, sexual acts with a person incapable of resistance are classed as rape, punishable by up to ten years in prison.

The accused, however, maintains that he and the nurse had previously kissed, a claim she denies.

This clash of accounts will likely turn on medical evidence, consent interpretation, and credibility assessments, which Swiss courts weigh carefully in sexual-assault proceedings.

Since 2024, prosecutors have been unable to locate the suspect.

If he is indeed in Australia, his return to Switzerland may hinge on complex extradition procedures governed by the 1974 Switzerland–Australia Treaty.

Switzerland can issue an Interpol Red Notice, effectively alerting global law enforcement that he is wanted for rape.

But unless Australia acts on the request, the notice remains only a warning.

This case underscores how international justice can falter when the accused disappears, leaving victims waiting for closure that may never come.

Under the Council of Europe Convention on Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters, which Australia joined in 1992, Swiss prosecutors can still request document sharing and testimony gathering.

For a detailed look at how international defense lawyers navigate extradition and cross-border cases, see our feature: Why Working with an International Criminal Defense Attorney Is Essential in Today’s Global Justice Landscape.

But without physical custody of the accused, trial in absentia becomes the only path - a process often criticized for its limited enforcement power.

In practical terms, even if convicted, the offender would remain free unless he entered Swiss or EU territory again.

Such limitations reveal why international criminal enforcement often feels more diplomatic than judicial.

The Schumacher family, who have guarded their privacy since Michael’s devastating 2013 ski accident, have no role in the case.

Still, Swiss privacy and press laws make this a sensitive matter.

Reporters must balance the victim’s right to anonymity with the public’s right to information, a balance shaped by European human-rights rulings under Article 8 of the ECHR.

As celebrity homes increasingly double as workplaces, lawyers anticipate a growing wave of litigation at the intersection of employment law, personal privacy, and criminal justice.

If the accused resurfaces, Swiss authorities could detain him immediately.

If not, the case may remain frozen - a haunting symbol of how cross-border sexual-assault prosecutions often stall when jurisdiction meets geography.

Meanwhile, the nurse may still pursue compensation under Switzerland’s Federal Victim Assistance Act, which offers financial and psychological support for victims of violent crime.

If a suspect leaves the country before charges are filed, the local prosecutor can still issue a warrant and request international cooperation. In most cases, authorities rely on Interpol Red Notices or extradition treaties to bring the suspect back to face trial, though the process can take months or even years.

Yes if a crime was committed on Swiss territory, Switzerland has territorial jurisdiction. However, the accused must be either extradited or voluntarily return to stand trial, since Swiss courts cannot enforce criminal sentences abroad without international cooperation.

Switzerland and Australia are bound by a 1974 Extradition Treaty, which requires both nations to recognize the offence as a crime (“dual criminality”). The Swiss government must submit detailed evidence through diplomatic channels, and Australian courts decide whether the extradition meets human-rights and legal standards.

Victims of sexual assault in Switzerland have the right to legal representation, anonymity, and compensation under the Federal Victim Assistance Act. They may also receive psychological support and financial aid from state-funded victim services while the case is investigated or prosecuted.

Under Article 190 of the Swiss Criminal Code, rape involves sexual acts carried out against a person’s will or when the victim is unable to resist due to unconsciousness or intoxication. The maximum penalty can reach ten years in prison, depending on the severity of the act and aggravating factors.

Not unless negligence can be proven. Swiss civil law requires property owners to maintain a safe environment, but criminal liability for third-party acts generally applies only if they failed to take reasonable preventive measures.

If a country refuses extradition, prosecutors may try the case in absentia or pursue mutual legal assistance to collect evidence. However, enforcement of any conviction is limited the suspect remains free unless they enter a jurisdiction willing to enforce the sentence.