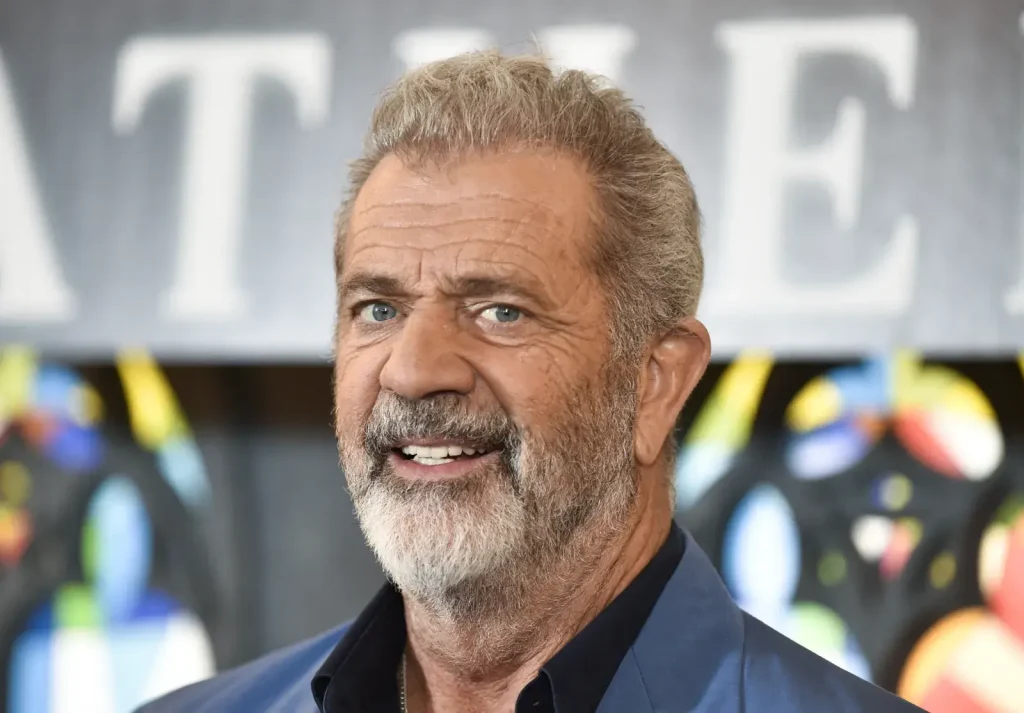

Mel Gibson’s Passion Sequel Faces Legal Scrutiny After Recasting Jesus Without Jim Caviezel

More than twenty years after The Passion of the Christ reshaped faith-based cinema, Mel Gibson’s upcoming sequel, The Resurrection of the Christ, has already sparked legal questions and public outrage.

The director’s decision to recast Jesus and Mary Magdalene, replacing Jim Caviezel and Monica Bellucci, has opened debate over actor contract rights, AI likeness law, religious freedom, and international film censorship.

As production begins in Italy, industry lawyers are now asking whether Caviezel, who for years spoke publicly about returning could have any legal claim for being replaced.

Caviezel’s situation illustrates a common grey area in entertainment law. Actors sometimes rely on verbal assurances or past collaborations when assuming they’ll reprise a role, but that doesn’t always create a binding agreement.

Without a sequel clause or first-refusal right, studios retain full casting discretion.

Still, if a director’s promise or public statement causes financial loss or reputational damage, a claim for promissory estoppel or breach of implied contract may arise rare, but possible under California law.

Can an Actor Sue for Being Recast in a Movie?

Usually, an actor cannot sue for being replaced unless a written contract guaranteed the role or first refusal. Under U.S. entertainment law, filmmakers have broad creative freedom to change their cast.

Jim Caviezel pictured as Jesus Christ in Mel Gibson’s 2004 film The Passion of the Christ.

However, if a studio or producer made a specific promise and the actor relied on it to their detriment, that could form the basis of a limited legal claim. In plain terms, being recast isn’t illegal, breaking a promise that caused financial harm can be.

The sequel’s legal complexity doesn’t stop there. Gibson reportedly avoided using costly de-aging effects, but doing so also helped him sidestep a fast-evolving issue: AI likeness rights.

Under California Civil Code § 3344, an actor’s image, voice, or likeness cannot be used for commercial purposes without written consent.

Had Gibson digitally recreated Caviezel’s younger face, it might have triggered a right-of-publicity violation, an issue addressed in the SAG-AFTRA 2023–24 AI Contract Addendum, which requires explicit performer consent for digital replication.

Is AI De-Aging an Actor Legal in Movies?

Using AI or CGI to de-age an actor is legal only if the performer gives written consent. Under U.S. law, and particularly California’s right-of-publicity statute, an actor’s likeness cannot be used commercially without permission.

If a studio recreates or alters an actor’s face digitally even for continuity they must negotiate rights through a contract or union agreement.

In plain English, filmmakers can legally use AI to make actors look younger, but only when the actor agrees to it.

Unauthorized use of a performer’s likeness, even in part, could be treated as identity misuse or digital impersonation, now a central issue in post-strike Hollywood.

Religious expression law adds another layer. While Gibson’s creative choices are shielded by the U.S. First Amendment, other jurisdictions apply stricter rules.

In Pakistan, Greece, Poland, and India, blasphemy and defamation laws can restrict films that depict sacred figures in controversial ways.

Distribution in those regions must comply with national legislation such as India’s Cinematograph Act, 1952 and Pakistan Penal Code § 295, which criminalize depictions considered offensive to religious sentiment.

For background on how these provisions have been applied in practice, see Amnesty International’s report on Pakistan’s blasphemy laws (PDF).

Studios such as Lionsgate, backing the production, will have to conduct careful legal vetting before release.

Filming in southern Italy brings its own obligations. The production’s chosen locations Matera and Altamura, fall under Italy’s Codice dei Beni Culturali e del Paesaggio, requiring special permits for shoots in religious or historic sites.

Italy’s film-tax credit program offers up to 40 percent reimbursement for qualifying productions, but compliance with labor, insurance, and safety rules is mandatory.

After Caviezel’s near-fatal injuries during the 2004 shoot, insurers are expected to impose stricter oversight this time.

Casting Finnish actor Jaakko Ohtonen as Jesus has also reignited debate over representation and authenticity in religious storytelling. Critics accuse Gibson of perpetuating the “white Jesus” stereotype, while others defend artistic license.

Legally, casting decisions fall under artistic freedom, but reputational and defamation concerns can still arise abroad in countries with hate-speech or religious-sensitivity laws.

The controversy shows how cultural representation and legal liability increasingly overlap in modern cinema.

Faith-based advocacy groups could also test boundaries under local “religious-protection” statutes if the film is deemed offensive.

Though such complaints rarely succeed, they can delay release and complicate distribution contracts, particularly in the EU and parts of Asia where religious defamation remains actionable.

In effect, The Resurrection of the Christ isn’t just a film; it’s a case study in how contracts, digital identity, cultural rights, and freedom of expression collide on the global stage.

Recasting Jesus may be a creative act, but it reveals how filmmaking today is governed as much by law as by art touching on contracts, AI likeness, and cross-border faith regulation.

Similar questions of ownership and identity have emerged elsewhere in Hollywood, explored in Val Kilmer’s Legacy: Who Controls His Voice and Image?, which examines how digital technology challenges an actor’s control over their likeness and performance rights.

People Also Ask

Can an actor sue for being recast in a movie?

Usually, an actor cannot sue for being replaced unless a written contract guaranteed the role or gave them first refusal. However, if a producer made a clear promise and the actor relied on it to their detriment, it could lead to a limited legal claim for promissory estoppel or breach of implied contract.

Is AI de-aging an actor legal in movies?

Yes — but only when the performer gives written consent. Under U.S. right-of-publicity laws and union agreements, filmmakers must obtain permission to digitally recreate or alter an actor’s likeness.

What is Pakistan’s blasphemy law?

Pakistan’s blasphemy laws, found in its penal code, criminalize speech or imagery considered offensive to religion. The penalties range from fines to life imprisonment or death, depending on the severity of the perceived offense.

What is India’s Cinematograph Act?

The Cinematograph Act of 1952 gives India’s Central Board of Film Certification the power to review, edit, or ban films before release if they are deemed offensive, immoral, or harmful to public order.

Why is Mel Gibson’s Passion sequel controversial?

The controversy surrounds Mel Gibson’s decision to recast Jesus and Mary Magdalene, replacing Jim Caviezel and Monica Bellucci. Critics say it raises legal, ethical, and cultural questions about representation and the boundaries of artistic freedom.