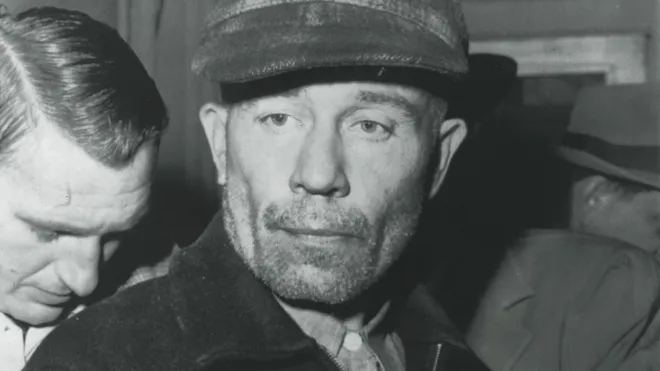

When Ed Gein was arrested in Plainfield, Wisconsin, in 1957, the world learned what America had long been trying to deny — that the grotesque was not foreign or cinematic, but homegrown.

The small-town handyman who turned human remains into lampshades and furniture became more than a criminal curiosity. He was a mirror. Beneath postwar America’s veneer of optimism lay repression, loneliness, and moral rigidity — the perfect soil for a monster who seemed to emerge from within the culture itself.

Decades later, his story still refuses to die, resurfacing in films, books, and, most recently, Netflix’s Monster: The Ed Gein Story (2025). Each retelling says less about Gein and more about the era obsessed with him.

Mid-century America prided itself on neat lawns, nuclear families, and church attendance. Yet that postwar order came at a psychological cost. Veterans returned from World War II scarred but silent; women were pushed back into domesticity after years of wartime labor. In small towns like Plainfield, repression became a civic virtue. Religion, particularly of the fire-and-brimstone kind, defined morality in absolutes. Desire was dangerous. Curiosity was shameful.

Ed Gein grew up under that ethos — a son raised by a domineering mother who preached that women were sinful and that pleasure was the devil’s snare. In a country obsessed with purity, Gein became a grotesque parody of its ideals. According to The New York Times, cultural historians often describe Gein not as a deviation from postwar America but as an extension of it — “the nightmare lurking under the picket fence.”

When the grisly details of Gein’s crimes emerged, they didn’t just horrify; they fascinated. Reporters described the farmhouse like a purgatorial chapel, its furniture of flesh an altar to maternal guilt. The obsession wasn’t only about the horror of what he’d done, but the deeper terror that his madness was an exaggerated version of the same moral claustrophobia America had built for itself.

Within a few years, Gein was reborn as fiction. Robert Bloch, who lived just 40 miles away, turned his crimes into Psycho (1959). Hitchcock’s 1960 adaptation turned Norman Bates into an archetype: the dutiful son, the repressed man-child, the killer next door. From there came Leatherface in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs (1991), and countless others — cinematic echoes of a single Midwestern figure.

Each iteration transformed Gein into something new: a warning about the dangers of repression, a symbol of rural decay, or a vessel for urban America’s fear of the countryside. The monster was never static. As the decades passed, Gein’s legend evolved with the anxieties of each generation. In the 1970s, he reflected fears of isolation and madness; in the 1990s, psychological disorder; in the 2000s, toxic masculinity and media obsession.

Now, in 2025, Monster: The Ed Gein Story has revived him again — this time for the streaming generation.

Ryan Murphy’s Monster: The Ed Gein Story premiered on Netflix in October 2025, starring Charlie Hunnam as Gein and Laurie Metcalf as his mother. Pop star Addison Rae portrays Evelyn Hartley, a young babysitter who vanishes — a fictionalized nod to a real unsolved disappearance from 1953. According to The New York Times, Murphy conceived the series after revisiting Psycho as a child and realizing that Gein was the connective tissue between America’s real crimes and its cinematic nightmares.

But the release has already stirred controversy. Gein’s biographer Harold Schechter criticized the show for “inventing relationships that never existed,” calling it “a fantasy about fantasy.” Critics in The Independent and RogerEbert.com accused the series of “aestheticizing horror,” framing Gein’s trauma as art direction rather than pathology. Even Hunnam admitted to People magazine that he “panicked” after taking the role, worried it would consume him psychologically.

In truth, Monster is not about Ed Gein at all — it’s about the 21st century’s insatiable appetite for the monstrous. Streaming platforms have turned true crime into a form of ritual, replayed endlessly until horror becomes comfort. The camera lingers not on the victims but on the man behind the mask, asking the audience to empathize, then recoil, then empathize again.

To understand why Gein still haunts American culture, one must look beyond the crimes to what they symbolized. Gein emerged during a period when masculinity, sexuality, and faith were tightly policed. He lived alone after his mother’s death, surrounded by religious tracts, anatomy books, and tabloid headlines about missing women. His crimes were acts of desecration — not only of bodies but of social boundaries.

Psychologists at the time diagnosed him with schizophrenia and necrophilia, yet that clinical language barely touched the cultural wound. As author Harold Schechter wrote, “Gein was the literal embodiment of everything the 1950s denied: death, decay, desire.” His house became the shadow version of suburbia — what happens when repression, instead of producing order, produces madness.

The American monster myth thrives on contradiction. We need killers who come from somewhere, not nowhere, so we can believe we’d recognize them if we met them. But Gein complicates that. He was local, polite, helpful. He attended church. He was the man who fixed your fence. In a way, he was the price of our own conformity.

Ed Gein’s trial in 1957 also shaped how America understands criminal insanity. He was declared “not guilty by reason of insanity” and committed to Central State Hospital for the Criminally Insane rather than prison. Under Wisconsin law, a defendant must lack the capacity to appreciate the wrongfulness of their acts to qualify for the insanity defense. Gein’s delusions — his belief that he could resurrect his mother through human skin — met that threshold.

He would remain institutionalized for the rest of his life. When he was finally deemed competent to stand trial in 1968, he was convicted of a single count of murder but immediately returned to the hospital. He died there in 1984.

Today, the legal landscape around the insanity defense remains narrow. The standard established by M’Naghten’s Case (1843) in English law and later modified in U.S. statutes requires proof of an inability to distinguish right from wrong. Some states, like Montana and Idaho, have abolished the insanity defense entirely, substituting “guilty but mentally ill.” Critics argue this blurs justice and psychiatry; defenders say it prevents offenders from escaping punishment.

Gein’s case remains a touchstone in forensic psychology classes — a reminder that criminal law often struggles to reconcile horror with pathology. His confinement was as much about moral quarantine as mental health. Society needed him contained, but it also needed to keep looking at him.

Every generation invents its own version of Ed Gein. The 1970s had the Zodiac Killer — elusive, intellectual, faceless. The 1980s gave rise to Ted Bundy, handsome and manipulative. The 1990s introduced the Menendez brothers, whose murders of their parents shocked a culture obsessed with image and inheritance. Each case reflected a specific American dread: the unknowable stranger, the charming sociopath, the collapse of the family ideal.

But Gein is the prototype — the first to turn murder into myth. His crimes were so extreme they became metaphorical. When modern audiences stream Monster, they aren’t just watching a man lose his mind; they’re revisiting the birth of the American nightmare.

The media, of course, continues to refine this mythology. According to All That’s Interesting, Gein’s Plainfield farmhouse became a kind of dark tourist site even after it burned down in 1958, with visitors collecting soil, nails, and pieces of debris. The desire to touch horror — to bring it home — mirrors the same impulses that created true crime as entertainment.

What makes Gein’s story uniquely American isn’t just the violence but the theology behind it. His fixation on flesh was not erotic in the traditional sense — it was religious. His crimes reenacted, in perverse form, the rituals of death and resurrection he’d heard preached every Sunday. Gein wasn’t trying to defy God; he was trying to imitate Him.

According to The New York Times, religious scholars see in Gein’s obsession with bodily transformation a twisted reflection of Christian resurrection imagery — “a rural mysticism gone rotten.” In this light, Gein becomes less a monster than a blasphemer, acting out America’s confusion between salvation and control.

This fusion of faith and violence still permeates the genre. Modern serial killer stories — from True Detective to Dahmer — draw on the same gothic spirituality. The killer is both sinner and prophet, condemned yet illuminating what society refuses to see.

That paradox has only deepened in the streaming age. Monster: The Ed Gein Story doesn’t exist in isolation; it’s part of an industry that packages tragedy as prestige television. Addison Rae, a pop influencer, now plays a murdered babysitter. The line between victim, celebrity, and commodity collapses.

Netflix markets the series as a “psychological exploration,” but the format itself invites moral ambiguity. As media critic Alexis Soloski wrote in The New York Times, Murphy’s version “seeks the man behind the mask — and ends up staring into a mirror.” True crime today isn’t about solving mysteries. It’s about consuming pain as content.

For audiences, that consumption can feel both transgressive and cleansing. Watching Gein’s story again, with cinematic gloss and expensive lighting, allows us to process collective guilt at a safe distance. Horror becomes ritual, replayed until numbness sets in.

What endures about Ed Gein is not the crime scene but the reflection it casts across time. Every retelling — from Psycho to Monster: The Ed Gein Story — revisits the same haunting theme traced throughout the Ed Gein timeline: isolation, delusion, and the slow corrosion of morality in the absence of empathy.

Gein’s legacy has become a study in projection. We return to him not out of fascination with brutality, but because his story mirrors our collective unease — loneliness, repression, and a culture frightened by its own desires. As one cultural historian observed, “Gein is America stripped of its costume — a nation stitching together identities from the dead.”

The Ed Gein timeline therefore reads less like a series of crimes and more like a psychological mirror held up to the twentieth century. He remains, half-man, half-metaphor — haunting the edges of our culture, reappearing whenever America tries to bury what it cannot destroy: the knowledge that the real monster was never hiding in the woods. It was in the mirror all along.

Why is Ed Gein still relevant in 2025?

Because every new generation remakes him in its own image — from Psycho to Netflix’s Monster: The Ed Gein Story — reflecting how American culture processes guilt, repression, and fascination with the grotesque.

Was Ed Gein found legally insane?

Yes. He was declared not guilty by reason of insanity in 1957 and confined to Central State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, where he remained until his death in 1984.

What did Ed Gein’s crimes inspire?

His crimes inspired Norman Bates (Psycho), Leatherface (The Texas Chain Saw Massacre), and Buffalo Bill (The Silence of the Lambs).

Why does Netflix’s Monster series focus on him now?

The 2025 season revisits Gein’s story as a reflection of modern America’s obsession with true crime, identity, and the blurred line between empathy and exploitation.