When Towers Threaten Rivers: What Trump Tower's $4.8M Settlement Says About Corporate Water Use and the Law.

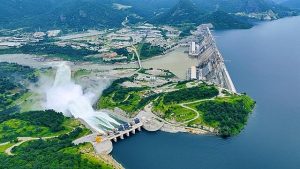

It’s not every day that a skyscraper ends up in hot water—literally and legally. But that’s exactly what happened with Trump Tower Chicago, which recently agreed to a $4.8 million settlement after years of improperly drawing millions of gallons of water from the Chicago River for its cooling systems. The case may sound like a one-off, but it taps into something deeper: the silent damage corporations can do to aquatic ecosystems—and how the law is finally starting to catch up.

At its heart, this story isn’t just about a permit violation or a high-rise on the Chicago skyline. It’s about how we, as a society, protect shared natural resources in an age of industrial scale, urban growth, and environmental vulnerability. And it's a reminder that when corporations cut corners on environmental compliance, it's often rivers, fish, and the public that pay the price.

How Water Laws Work—and What Went Wrong at Trump Tower

The legal backbone of U.S. water protection is the Clean Water Act (CWA), a landmark law passed in 1972. Its mission is simple on paper: to "restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation's waters." But putting that into practice—especially in major cities—can be complex.

One key part of the Clean Water Act is Section 316(b), which deals specifically with how companies take in water from rivers, lakes, or other public sources—usually for cooling machinery or regulating building temperatures. These “cooling water intake structures” may sound harmless, but the environmental cost can be steep.

Trump Tower, for instance, was drawing nearly 20 million gallons a day from the Chicago River—without proper permits from the state and with little concern for how that process affected local fish and aquatic life. The building’s intake system lacked the necessary protections to prevent harm, and its operators reportedly failed to report accurate water use data.

That noncompliance triggered lawsuits, not only from regulators but also from environmental nonprofits who used citizen suit provisions built into the Clean Water Act. These provisions allow everyday people—and the organizations that represent them—to step in when the government fails to act.

The Hidden Harm of Cooling Systems: A Fish's-Eye View

To understand the environmental impact of large-scale water withdrawal, think small—like, microscopic. Fish eggs, larvae, plankton—these tiny organisms form the base of the aquatic food web. When water is sucked into a building’s cooling system, they’re either impinged (smashed against intake screens) or entrained (pulled into the machinery and effectively destroyed).

It’s not just the little guys that suffer. The cumulative damage disrupts the river’s entire ecosystem. Heated water is often discharged back into the river—a phenomenon known as thermal pollution—raising water temperatures and lowering oxygen levels, both of which can be fatal to aquatic species.

That’s why laws require companies to use the “best technology available” (BTA) to minimize harm. In many cases, that means investing in closed-loop systems that recirculate water instead of pulling it in fresh every time. Trump Tower’s system, however, fell far short of that standard.

What Happens When Corporations Ignore the Rules

The $4.8 million Trump Tower settlement is more than a slap on the wrist. It includes penalties and funding for fish habitat restoration in the Chicago River—one of the most degraded urban waterways in America, but also one with a growing conservation movement.

It’s also an example of how environmental law works in layers:

-

Permitting and Compliance: Facilities must have valid water intake permits and must adhere to technology standards. Trump Tower skipped key steps here.

-

Public Nuisance Law: Illinois called the building a public nuisance—a legal term for any activity that harms public welfare. In this case, it was the health of a public river.

-

Citizen Enforcement: Groups like the Sierra Club and Friends of the Chicago River helped hold the tower accountable using legal tools meant to empower the public.

This kind of multi-pronged legal pressure is becoming more common, especially as citizens grow frustrated with regulatory slowdowns and environmental backlogs.

Bigger Lessons: The Real Cost of Cutting Corners

This case taps into a much larger conversation about corporate responsibility in the face of environmental damage. What stands out isn’t just what Trump Tower did wrong—it’s what the case teaches all companies that use natural resources.

1. Noncompliance is Expensive:

Beyond fines, violations can lead to lawsuits, public backlash, and brand damage that lasts far longer than a legal settlement.

2. Proactive Beats Reactive:

The best companies build environmental compliance into their business models from day one. It’s cheaper, safer, and better for everyone than scrambling after you’re caught.

3. Environmental Advocates Matter:

Organizations like Friends of the Chicago River don’t just raise awareness—they file lawsuits, push for regulatory change, and ensure corporate polluters face consequences.

4. Rivers Are Public Trusts:

The Chicago River isn’t just water—it’s history, ecology, and community. Cases like this affirm that natural resources are held in trust for the public, not to be exploited for private gain without oversight.

5. Standards Are Always Evolving:

What passed muster in 1995 might be illegal today. Environmental science and policy evolve, and corporations must evolve with them or face legal—and ecological—repercussions.

Final Thoughts: Beyond the Tower, Toward a Sustainable Future

It’s easy to treat a story like this as a Trump-era curiosity—another headline with a big name and a dollar figure attached. But that misses the point.

This case is part of a broader reckoning. Cities are growing, industries are expanding, and the strain on natural ecosystems is becoming more visible and less tolerable. Water, once treated as an infinite resource, is now recognized for what it is: precious, fragile, and deeply connected to the health of our communities.

Environmental law isn’t just about compliance—it’s about values. And the Trump Tower case reminds us that when corporations forget that, the courts—and the people—are ready to remind them.

People Also Ask (SEO Section)

How does water intake affect fish and aquatic life?

Large-scale water intake can trap or kill fish and other small organisms through impingement and entrainment, disrupting local ecosystems.

What is the Clean Water Act Section 316(b)?

It mandates that facilities using cooling water intake structures must minimize environmental impact using the best technology available.

What is a public nuisance in environmental law?

A public nuisance is an activity that harms public resources, like rivers, making them unsafe or unusable for the community.

Can citizens sue companies for environmental violations?

Yes. The Clean Water Act allows for citizen suits, enabling nonprofits and individuals to take legal action when regulators do not.