The Sackler family’s role in the U.S. opioid epidemic remains one of the most troubling unresolved questions in American justice. Despite billions in settlements over OxyContin’s marketing, no Sackler has ever faced criminal prosecution. Here’s why that may never change—and what the law still allows.

On 23 January 2025, Purdue Pharma and members of the Sackler family agreed to pay up to $7.4 billion (£6 billion) to settle claims that the company’s prescription painkiller OxyContin helped fuel the American opioid crisis. The agreement—an increase of more than $1 billion over a prior deal rejected by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2024—was reported by BBC News, Reuters, and the Associated Press.

Under the terms of the new deal, the Sacklers will contribute up to $6.5 billion, while Purdue Pharma will add $900 million. The money will fund addiction treatment and prevention programmes across the United States. The settlement still requires formal approval from a U.S. bankruptcy court, but it represents one of the largest corporate payouts in the history of American public health litigation.

Yet the announcement reignited a question that has haunted the case for years: despite the billions paid and the devastating loss of life, no Sackler family member has faced criminal charges.

The Sackler story began in Brooklyn, New York, where brothers Arthur, Mortimer, and Raymond Sackler—the sons of Jewish immigrants from Poland—trained as doctors in the 1940s. Arthur, the eldest, was a pioneer in medical advertising who helped transform pharmaceutical marketing into a data-driven industry.

In 1952, the brothers purchased a small drug company, Purdue-Frederick, which later became Purdue Pharma. After Arthur’s death in 1987, his brothers and their heirs expanded Purdue’s focus to pain management—an area that was under-treated but lucrative.

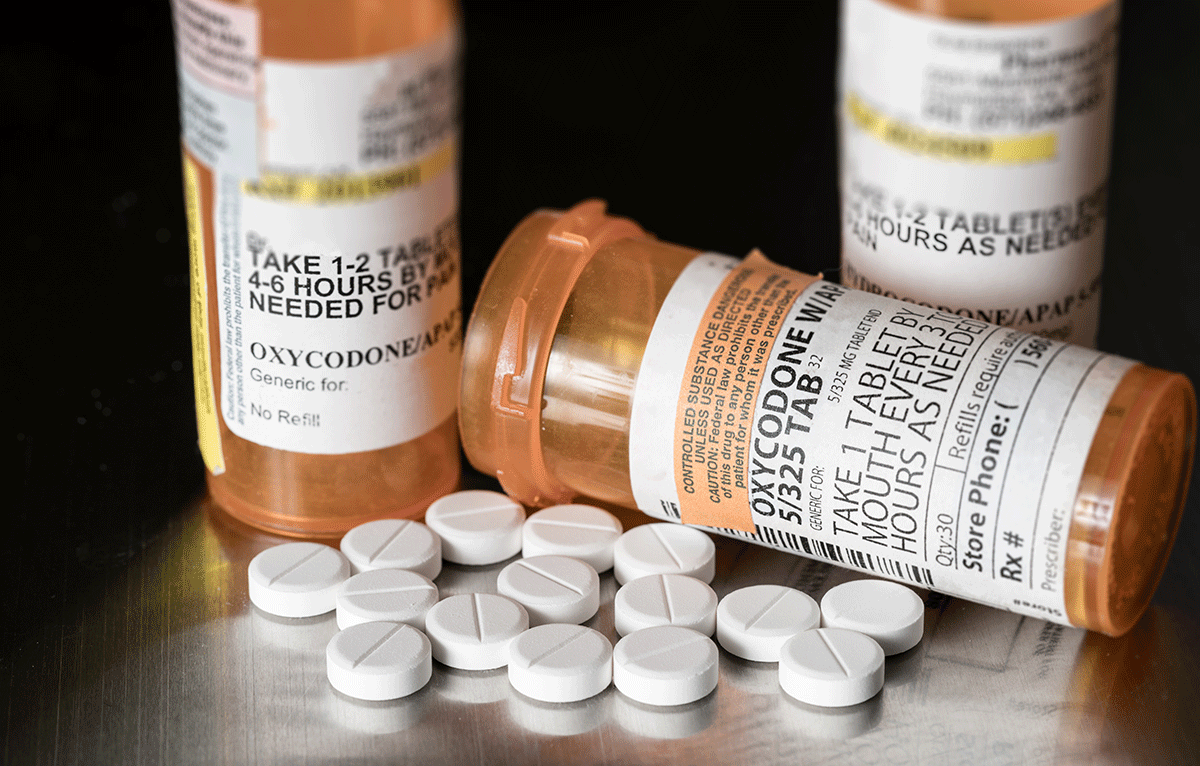

Their breakthrough came in 1996, when Purdue launched OxyContin, a slow-release formulation of oxycodone. Marketed as a safe and long-acting painkiller, it was touted as “less addictive” than earlier opioids. In reality, the drug’s potency and addictive potential were severely underestimated—or deliberately downplayed. Within a few years, OxyContin became both a blockbuster and a public health disaster.

Internal company documents later revealed that Purdue trained its sales force to “overcome physician hesitation” about prescribing opioids. Representatives were rewarded for higher sales, and doctors were flooded with promotional materials that misrepresented OxyContin’s risks.

By the early 2000s, prescriptions had skyrocketed, spreading addiction into rural and suburban communities across America. According to CDC data, opioid overdoses have claimed more than 500,000 lives since 1999.

At the centre of Purdue’s marketing push was Richard Sackler, who served as company president from 1999 to 2003. In internal emails unsealed by the courts, he encouraged aggressive sales strategies even as addiction rates soared. “We have to hammer on the abusers,” he wrote in one memo. “They are the culprits and the problem.”

In 2007, Purdue Pharma pleaded guilty in federal court to misbranding OxyContin, admitting that it had misled doctors and patients about the drug’s addiction risks. The company paid $634 million in fines. Three executives were convicted—but none of them were members of the Sackler family.

The U.S. Department of Justice handled the case as a corporate matter rather than a personal one. The Sacklers, as owners and board members, escaped individual prosecution. Critics later called the plea deal a turning point in American corporate law: proof that a company could commit a crime without sending any of its owners to prison.

By 2021, facing more than 3,000 lawsuits from states, cities, and Native American tribes, Purdue filed for bankruptcy protection. Its first settlement proposal, valued at $6 billion, sought to shield the Sackler family from future civil lawsuits.

In August 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected that plan, ruling that non-bankrupt individuals cannot receive immunity through a corporate bankruptcy case. The family then returned to the negotiating table, agreeing in January 2025 to the $7.4 billion settlement now awaiting court approval.

Under the deal, Purdue will be restructured into a public-benefit corporation, directing future profits to addiction recovery and education. But for many victims and legal experts, the settlement feels hollow. Financial accountability has come—but criminal accountability has not.

For decades, the Sackler name was a fixture of elite philanthropy, emblazoned on museum wings and university buildings from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to the Louvre in Paris. That changed as the lawsuits mounted.

Artist and activist Nan Goldin, herself a survivor of opioid addiction, led global protests urging institutions to “refuse Sackler money.” By 2023, nearly all major museums had removed the family’s name.

The backlash fractured the family itself. Madeleine Sackler, an Emmy-winning filmmaker, publicly distanced her work from Purdue. Meanwhile, Richard Sackler continued to defend the company, insisting in testimony before Congress that Purdue’s marketing was “lawful and appropriate.” His words only deepened public outrage.

The most enduring mystery of the opioid crisis is why, despite overwhelming evidence of harm, no Sackler has been criminally charged. The answer lies in the narrow way U.S. law defines corporate crime.

Under the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (21 U.S.C. § 331) and the Controlled Substances Act (21 U.S.C. § 801 et seq.), prosecutors must prove that a specific individual knowingly and intentionally misled regulators or distributed a dangerous drug unlawfully. Proving that level of intent at the executive level is extraordinarily difficult.

“Intent is the wall you can’t climb,” said Professor Andrew Kolodny, medical director of Opioid Policy Research at Brandeis University. “The Sacklers made the decisions, but through layers of executives and lawyers. That insulation makes criminal charges nearly impossible, even if the moral responsibility is obvious.”

A 2020 New York Times investigation revealed that federal prosecutors had considered filing criminal charges against individual Sackler family members, but senior Justice Department officials declined, citing insufficient evidence to prove direct fraud.

Former U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara later remarked in interviews that corporate hierarchies often make it easier to indict a company than the wealthy individuals behind it, a dilemma that has defined much of the Sackler controversy.

The Purdue case has become a textbook example of a broader flaw in American corporate law: the near-impossibility of holding executives criminally liable for systemic harm.

Other countries have taken a different approach. The U.K.’s Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act (2007) allows companies—and their leaders—to be prosecuted when management failures cause death. No equivalent law exists in the United States.

Several U.S. lawmakers have introduced proposals to change that. Senator Elizabeth Warren’s Corporate Executive Accountability Act, for instance, would make top executives criminally liable for “negligent harm” caused by their companies. But as of early 2025, such reforms remain stalled in Congress.

“The law lags behind morality,” said Professor Miriam Baer of Brooklyn Law School. “When corporations kill, the people behind them often walk free. That’s the enduring lesson of Purdue Pharma.”

For communities devastated by addiction, the absence of criminal charges feels like a failure of justice. Since 1999, opioid overdoses have surged to tens of thousands of deaths each year, often starting with legal prescriptions.

“The justice system doesn’t balance when billionaires can sign a cheque and walk away,” said Kara Trainor, a Michigan woman who became addicted to OxyContin after a back injury and has been in recovery for 17 years. “Everything in my life was shaped by a company that put profit over people.”

While the 2025 settlement will fund treatment and prevention programs nationwide, critics argue that money cannot replace accountability. “There isn’t enough money in the world to make it right,” Connecticut Attorney General William Tong told Reuters.

Despite the settlement, several state attorneys general continue to review sealed Purdue documents that could reveal more direct family involvement. These include internal communications, board minutes, and emails spanning from 1995 to 2019.

Tong has stated publicly that “the door isn’t closed.” If those records show deliberate concealment of addiction data or efforts to obstruct investigations, prosecutors could pursue criminal fraud or obstruction charges.

Still, most legal experts consider this unlikely. Statutes of limitation and the difficulty of proving intent make new prosecutions improbable. But the disclosure of more than 13 million internal documents, a requirement of the new settlement, may reshape future cases involving corporate harm.

If the court approves the 2025 deal, Purdue Pharma will be reborn as a public-benefit trust, temporarily known as Knoa Pharma, dedicated to funding addiction recovery, education, and overdose prevention.

The Sacklers will lose ownership of the company, but according to court filings and the New York Attorney General’s Office, they still retain an estimated $6–8 billion in personal assets. Much of that money was transferred out of Purdue between 2008 and 2019, including around $11 billion withdrawn in the decade before bankruptcy—some of which was moved offshore.

For many, the family’s punishment has been reputational, not criminal. Their name has been erased from museum walls and academic buildings, but their fortune endures.

Financial records have also revealed how the Sacklers safeguarded parts of their fortune as legal scrutiny intensified. In an investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and The Art Newspaper (24 October 2018), it was reported that Mortimer Sackler and his family held $31.2 million in private HSBC accounts in Switzerland, opened in 2005—just one month before U.S. federal prosecutors filed a lawsuit against Purdue Pharma.

The HSBC files, first leaked by whistleblower Hervé Falciani, linked the Sacklers to multiple offshore trusts and companies registered in Jersey. While the documents did not suggest wrongdoing, they revealed the family’s extensive offshore financial activity as Purdue faced mounting legal challenges over OxyContin’s marketing.

That same London-based branch of the Sackler family went on to donate nearly £80 million to U.K. museums, galleries, and universities through the Sackler Trust and the Dr. Mortimer and Theresa Sackler Foundation, even as cultural institutions later severed ties in response to public pressure.

Under current U.S. law, the odds of criminal prosecution against the Sackler family remain slim. The challenge lies in proving personal intent beyond a reasonable doubt under statutes like the Controlled Substances Act and FDCA. Unless new documents reveal explicit evidence of deception or obstruction, criminal charges are improbable.

Still, the Sackler case has spurred renewed debate over executive accountability. Legal scholars and legislators alike now argue that systemic corporate wrongdoing—especially when it costs lives—demands a higher standard of personal responsibility.

As Professor Baer notes:

“The Purdue case will be remembered as the moment America began asking whether corporate crime can exist without a criminal.”

What is the Sackler family doing now?

Several family members live privately in Connecticut, New York, and London. They maintain investments through trusts and family offices but no longer control Purdue Pharma.

How much money does the Sackler family still have in 2025?

Estimates range between $6 billion and $8 billion after taxes, donations, and settlement payments.

Could the Sacklers still face criminal charges?

Possible, but unlikely. Prosecutors have found no direct evidence of individual intent; new discoveries in the Purdue document trove could reopen the question.

What laws protect executives from prosecution in corporate scandals?

Primarily the requirement to prove personal intent. Without direct evidence of knowingly illegal actions, liability stops at the company level.

How are opioid-settlement funds being used?

The 2025 plan allocates funds to state-run treatment centres, overdose-prevention initiatives, and recovery programmes across the U.S.

The courts may soon close the books on Purdue Pharma, but the human story behind the opioid epidemic remains painfully unfinished. The Sacklers built a fortune on pain—and now, decades later, their money is funding its relief.

For many families, that irony cuts deeper than any legal verdict. The balance sheet may be settled, but the moral debt endures.