When federal prosecutors announce charges tied to hacked social-media accounts, the conduct they describe often goes back years, long before the case ever becomes public.

That gap can feel baffling, especially for people who only realise they were affected once an investigation reaches the charging stage.

In many of these cases, the problem isn’t a technical breach of a platform like Snapchat. It’s that someone convinced users to give up access themselves.

Investigators say the most common pattern involves impersonation and misuse of account verification codes, with attackers gaining entry not by breaking systems, but by persuading people to hand over the very credentials meant to keep them out.

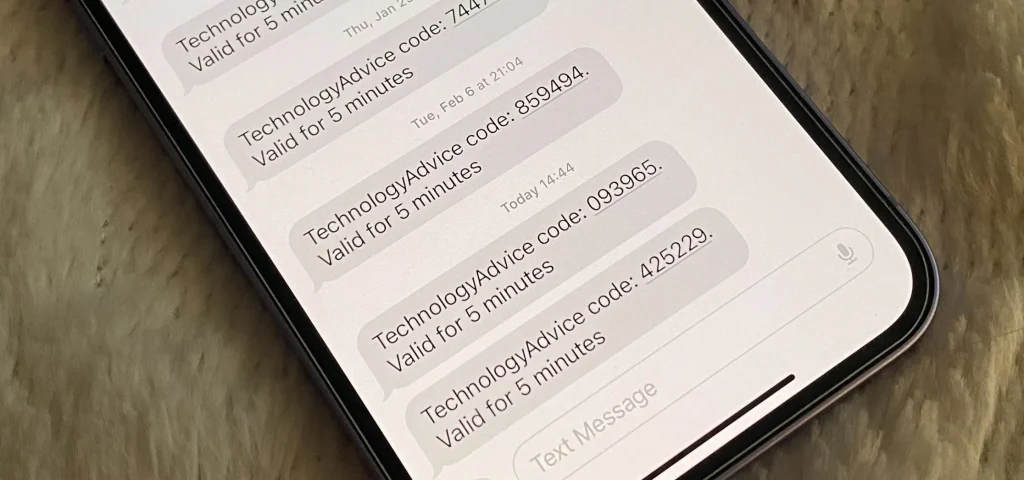

Most large social-media platforms rely on multi-factor authentication to protect user accounts. When someone logs in from a new device or requests a password reset, the platform sends a one-time verification code by text or email.

In phishing-based schemes, attackers don’t break into the platform itself. Instead, they work around it.

By gathering basic details such as usernames, phone numbers, or email addresses, they trigger those security prompts and wait for the code to be sent.

The attacker then contacts the user directly, often posing as customer support or a platform representative.

Because the request arrives at the same moment as a genuine security alert, it can feel routine rather than suspicious. Once the code is shared even briefly, the account can be accessed immediately, without the attacker ever needing the password.

A common misconception is that providing a one-time verification code is harmless, particularly if it happens quickly or under pressure. From an investigative standpoint, those codes function as digital keys tied directly to a specific account.

Law enforcement treats verification codes as protected access credentials. Using deception to obtain them and then using them to enter an account is legally different from clicking a malicious link or falling for a generic scam.

In federal cases, that distinction often determines whether conduct is viewed as careless misuse or as intentional unauthorised access.

For that reason, phishing investigations tend to focus less on the technology involved and more on the interaction itself: how the code was requested, how the victim was contacted, and how the attacker presented their identity during the exchange.

Sharing a verification code does not mean a user intended to grant access to their account. Investigators look closely at whether impersonation or misrepresentation was involved, and access gained through deception is treated differently from voluntary consent.

Not every hacked account results in a federal prosecution. Cases usually cross into federal territory when they involve interstate communications, a significant number of victims, or online services that operate across state lines.

Social-media platforms store data across multiple jurisdictions, and messages routinely pass through interstate networks.

That technical reality means account misuse can fall within the scope of federal wire and computer-fraud enforcement, even when both the victim and the suspect are located in the same state.

When investigators can point to coordinated conduct, such as repeated impersonation, anonymised communications, or the sale or exchange of stolen material, cases often expand beyond isolated account access into broader fraud and identity-misuse allegations.

Because messages, servers, and account data routinely cross state lines, many hacking cases involve interstate communications by default. That alone can be enough to trigger federal jurisdiction, particularly when multiple victims are involved.

One of the most confusing aspects for victims is the timeline. Many people only learn an investigation exists long after the alleged access occurred. That delay is usually structural rather than accidental, reflecting the way digital cases are built.

Investigators must first identify suspicious activity on a platform and then work with the company to trace logins, IP addresses, and device identifiers.

From there, court orders are often required to obtain subscriber information from phone providers, email services, or online forums.

In cases involving large numbers of victims, law enforcement must also confirm which accounts were accessed, what data was taken, and whether images or messages were shared elsewhere online.

Each step adds time, particularly when evidence spans multiple platforms or jurisdictions.

Federal cases typically become public only once investigators believe they understand the full scope of the conduct and who was involved. By the time charges are filed, much of the investigative work has already happened behind the scenes.

When a case reaches the charging stage, law enforcement may begin contacting potential victims, sometimes years after the alleged access. People are usually asked to confirm account ownership, describe any suspicious messages they received, and indicate whether content appeared to be missing or shared.

Being contacted does not mean investigators believe further harm occurred. In many cases, outreach is simply part of establishing the scope of the case and notifying individuals whose accounts were targeted.

Victims should not expect immediate updates, public disclosure of evidence, or guaranteed recovery of content. Federal cases move slowly, and victim notification is often only one part of a broader evidentiary process.

After initial contact, most victims hear very little for extended periods of time. This lack of communication reflects the pace of federal investigations rather than inactivity.

Federal cybercrime cases are not sentenced automatically based on headlines or the names of the charges involved.

Judges rely on sentencing guidelines that take into account factors such as the number of victims, the length of time the conduct occurred, the type of data accessed, and whether the activity was carried out for financial gain.

Statutory maximum penalties can sound severe, but actual sentences vary widely. Courts weigh the defendant’s role, any prior criminal history, and the specific harm proven at trial or acknowledged through plea proceedings.

For that reason, early charging announcements rarely predict final outcomes. Sentencing often takes place years after an investigation begins, following extensive motion practice, evidentiary disputes, and negotiated resolutions.

No. Charging announcements describe allegations, not outcomes. Final sentences depend on facts established later in the process and on judicial discretion.

Social-media platforms continue to strengthen their security systems, but phishing schemes target human behaviour rather than software flaws.

As long as platforms rely on verification codes and users tend to trust messages that appear to come from official sources, similar cases are likely to continue.

From a legal standpoint, these prosecutions are less about new laws and more about applying long-standing fraud and identity-misuse frameworks to modern digital conduct.

Understanding how these cases unfold helps explain why they often surface years after the underlying activity and why they are treated as serious federal matters rather than isolated online incidents.