When Suing the Government Creates Its Own Legal Risk

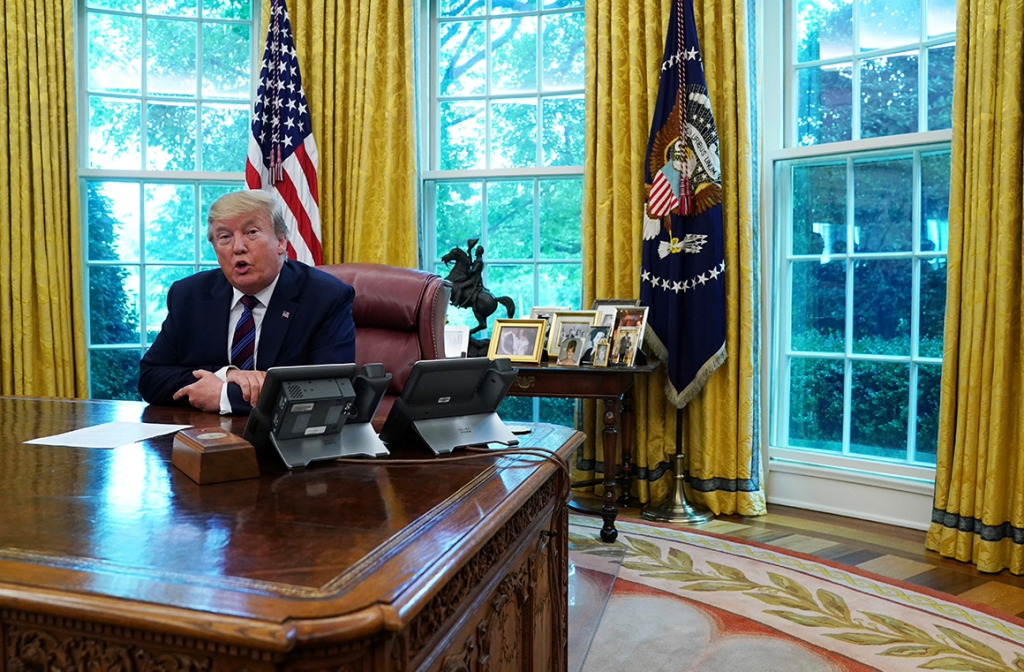

A civil lawsuit filed by Donald Trump against federal agencies over the handling of confidential taxpayer information highlights a legal exposure many people miss: once a claim is brought against the state, the claimant immediately enters a narrow procedural framework where timing, jurisdiction, and statutory immunity can determine the outcome before a court ever examines the underlying conduct.

Even where a breach is accepted as real, legal recovery is not automatic—and the act of suing can itself trigger cost, delay, and strategic disadvantage.

The legal issue beneath the headline

At the centre of cases like this is not whether confidential information should have been protected—that duty is usually clear—but whether the law permits a private individual to recover damages from the government at all.

Claims against public bodies operate under special rules. Statutes governing privacy breaches, administrative liability, and sovereign immunity strictly control who can sue, when they can sue, and what remedies are available.

Time limits are especially unforgiving. Many claims must be brought within a fixed period from when the claimant became aware of the breach, not when criminal proceedings conclude or when a responsible individual is convicted.

If that window closes, courts may be required to dismiss the case regardless of the seriousness of the underlying conduct. In practice, this means a claimant can be left with a confirmed breach but no legal pathway to compensation.

Practical impact before any ruling

Once litigation is filed against a government agency, several consequences follow immediately—even if the claim ultimately fails. Courts may first test whether they have jurisdiction, whether the claim is time-barred, and whether statutory protections block recovery entirely. These preliminary battles can consume years, absorb resources, and quietly exhaust a claim long before liability is tested.

There is also financial exposure. While the government often bears its own defence costs, unsuccessful claimants can still face procedural expenses, extended uncertainty, and the loss of alternative remedies that might have been available earlier. Civil litigation can also complicate parallel processes, including insurance recovery, regulatory complaints, or negotiated settlements.

Why this matters beyond the case

This legal structure does not apply only to high-profile disputes. The same principles affect ordinary individuals and organisations pursuing claims against tax authorities, regulators, local councils, or government departments. A data breach, administrative error, or misuse of information may feel actionable—but if statutory deadlines are missed or the wrong defendant is named, the claim can collapse.

Criminal accountability and civil compensation operate on separate tracks. A conviction against an individual wrongdoer does not automatically revive or extend a civil claim against the state.

For organisations, these limits often surface only after insurers, regulators, or counterparties begin asking whether a claim was still legally alive when action was taken. Waiting for a criminal outcome can, in some cases, quietly eliminate the civil one.

Legal takeaway

When a dispute involves a public authority, the greatest risk is often procedural rather than factual. Legal exposure arises the moment a claim enters the system, and delay alone can determine the result. Once a dispute enters the legal system, time itself becomes a form of risk—and delay can eliminate remedies even where wrongdoing is never in doubt.