Fritz Scholder Art Fraud Case: When Online Markets Trigger Federal Identity Law

Provenance in Native American art is not optional. It is statutory fact. When a seller claims a piece is created by a tribal artist, the claim activates federal law, not art-world convention.

The case against Gregory McBride, a 49-year-old Texas resident, became a blueprint for how cultural identity statutes stretch into online commerce, forensic proof, consignment liability, and marketplace evidence duties.

McBride was charged in New Mexico with fraud counts and violations under the Indian Arts and Crafts Act (IACA), a federal statute codified at 25 U.S.C. § 305e. The law exists to stop misrepresentation in Indian-produced goods, including tribally created art.

It is governed by the Indian Arts and Crafts Board (IACB) under the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI).

Enforcement duties sit with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), a federal investigative arm that operates within the DOI ecosystem, and prosecution decisions belong to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ).

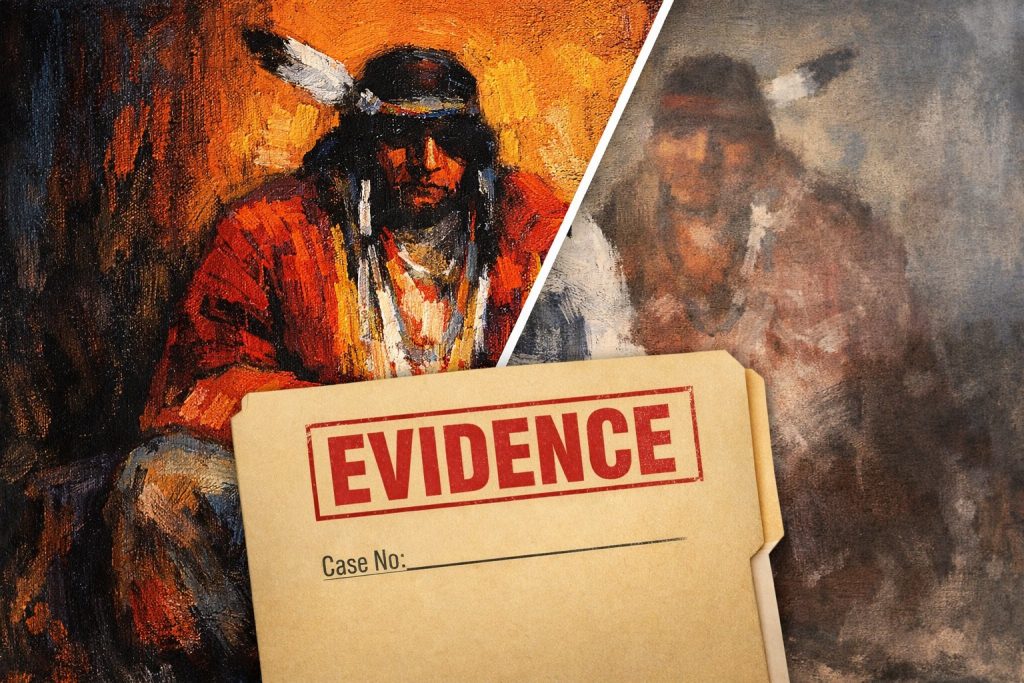

The affidavit alleges 76 paintings were falsely attributed to Fritz Scholder, a Luiseño tribal artist and educator at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in the 1960s.

Each sale is treated as a separate statutory event. The law does not bundle allegations. It itemizes them.

The consequence for sellers, galleries, platforms, and payment intermediaries is clear: once attribution is questioned in a complaint, institutions enter the evidentiary chain.

The New Custodians of Art Fraud Proof

The alleged fakes did not move quietly. They moved digitally. Listings on eBay, HiBid, and similar auction portals carried artist names, descriptions, timestamps, pricing, buyer accounts, and internal listing IDs.

Courts treat these records as commercial exhibits once subpoenaed or sworn into an affidavit. Platforms that store attribution data inherit duties to remove deceptive listings when alerted.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) enforces platform compliance expectations for listing takedowns tied to fraud complaints.

McBride’s marketplace ledger linked to payment rails processed through PayPal, Stripe, and standard bank transfer records.

Those records are not marketing history. They are institutional proof. Payment processors are logged because they tie listing attribution to buyer payment evidence.

The National Fish and Wildlife Forensics Laboratory, operated by USFWS, compared questioned signatures against authenticated Scholder exemplars archived through galleries and prior auction records.

When signatures diverge, the lab findings are sworn. They are not debated.

This changes commercial dynamics for platforms. In 2020, marketplaces positioned themselves as listing infrastructure.

In 2026, they are data custodians courts expect to cooperate with when deception is logged in a complaint.

The evidence trail becomes platform-owned proof that galleries, insurers, law firms, and prosecutors now treat as part of discovery, due diligence, and institutional exposure.

Consignment Possession and the New Burden on Galleries

When a buyer consigns a work, possession transfers. Liability questions follow.

McBride’s alleged fakes entered consignment houses including Windsor Betts Art Brokerage and Windsor Betts Art Brokerage consignment records in Santa Fe. These galleries did not authenticate the fakes. But they possessed them.

Consignment in Native-attributed art is now understood as a proof-sharing trigger when a federal identity statute is activated.

Before Santa Fe collector John Quintana died, he consigned three paintings he purchased from McBride to Windsor Betts Art Brokerage. Another buyer, Jeffrey Wade, consigned works tied to the same investigation.

Signature mismatches were sent to the National Fish and Wildlife Forensics Laboratory.

A sixth work was excluded from analysis due to image quality. The forensic findings were logged into the affidavit.

The affidavit now lives inside the filing ecosystem of the Fourth Judicial District Court of New Mexico, the state felony venue for the fraud counts.

Galleries that accept consigned Indian-attributed works now operate under the assumption that possession brings authentication duties once subpoenaed.

This shifts gallery governance, insurance underwriting, and attorney-client advice. In 2026, consignment houses face the question: what duty do you inherit when a tribal attribution claim is proven false? The answer is not artistic. It is statutory, forensic, and institutional.

The Outcome Matrix Table

| Former Status Quo | Strategic Trigger | 2026 Reality |

|---|---|---|

| Provenance disputes handled privately | Formal complaint to Indian Arts and Crafts Board + forensic signature mismatch | Multi-agency enforcement (FTC, USFWS, DOJ, NMOCC), platform data as exhibits |

| Marketplaces treated as neutral listing venues | Fraud-attributed tribal artist listings + payment processor trail | Marketplaces expected to remove listings when alerted; records become evidence |

| Consignment transfers possession, low legal consequence assumed | Fakes consigned before owner’s death | Possession triggers authentication and forensic proof-sharing obligations |

| Buyer sophistication influences severity | Complaint filed regardless of size or price | Cultural misrepresentation treated as market harm under federal law |

| Silence on refunds treated as non-event | Unanswered refund demand | Silence becomes institutional evidence logged into affidavits |

Why the Case Stays Active

The case is not one lane. It is multiple lanes. The New Mexico Organized Crime Commission (NMOCC) sought the arrest warrant through state authority.

The New Mexico State Police, Santa Fe Police Department, and Taos County Sheriff’s Office appear in the affidavit because they sit inside the state investigative chain. The USFWS supplies forensic proof and marketplace data.

The FTC supplies platform compliance expectations. The DOJ supplies prosecution ownership.

This overlap creates enforcement friction that keeps the case commercially relevant. When state fraud charges run in parallel to federal identity law violations, the case does not collapse into a single venue.

It escalates into layered venue pressure. The Fourth Judicial District Court of New Mexico holds the state felony counts. The U.S. District Court for the District of New Mexico becomes the federal venue if DOJ prosecutors file IACA counts federally.

The statute itself remains governed by the DOI through IACB ownership.

Venue pressure is not procedural nuance. It is leverage. For online sellers and brokers, every state named in an affidavit is a potential civil recovery jurisdiction or data subpoena node.

In this case, Scottsdale (Arizona) appears through Larsen Gallery, which authenticated questioned signatures and stores verified Scholder exemplars.

Santa Fe and Taos appear through buyers and consignment possession. Wimberley and Wimberly, Texas appear as the seller’s home geography, tying the listings to commercial identity claims.

Institutions that hold archives or possession now operate as proof nodes. They cooperate when subpoenaed. They do not narrate.

Commercial Stakes for Law Firms, Insurers, and Marketplaces

The Scholder case matters to more than collectors. It matters to commercial readers who advise institutions:

-

Insurers underwriting gallery consignment risk now include forensic authentication clauses in underwriting assumptions for Indian-attributed works.

-

Law firms advising art brokers now build compliance pillars around statutory labeling truth, platform takedown governance, and consignment proof-sharing obligations.

-

Marketplaces storing attribution records operate under the assumption that misattributed tribal art damages a protected cultural market, not just a buyer ledger.

-

Refund silence becomes evidence. It is logged in affidavits and later discovery.

-

Buyer sophistication does not reduce statutory severity. The law treats misrepresentation as market harm.

This case now informs governance advice delivered to senior commercial clients. The law does not reward good taste. It rewards statutory truth and proof delegation.

Final Authority Close

The U.S. Department of Justice holds the final authority on prosecution and federal liability decisions in Indian-attributed art fraud cases.

Legal Insight: 👉 Amazon Faces Renewed Liability Risk as Price-Gouging Litigation Clears Judicial Threshold 👈

People Also Ask

What is the precedent for liability under the Indian Arts and Crafts Act in online art sales?

The statute treats each sale as a separate offense when a seller mislabels a work as tribally created. Courts rely on sworn complaints logged by the Indian Arts and Crafts Board. The precedent is not artistic merit. It is identity misrepresentation tied to market harm.

How do marketplaces become evidence custodians in federal art fraud cases?

Platforms like eBay and auction portals store attribution, pricing, accounts, timestamps, and listing IDs. When subpoenaed, those records are treated as commercial exhibits. Neutrality ends once deception is logged in a complaint. The FTC expects listing removal compliance.

When consigned art is proven fake, who carries the forensic authentication duty?

The duty is inherited by possession holders once subpoenaed. Authentication is performed by forensic labs like the National Fish and Wildlife Forensics Laboratory. Proof is sworn, archived, and shared. It is not privately arbitrated.

What legal risk does a gallery inherit when accepting consigned tribal art?

Possession transfers documentation obligations. In 2026, galleries accepting Indian-attributed works operate under the assumption that consignment makes them proof nodes when identity fraud statutes activate. Insurance and law firm advice now treat consignment as a liability vector.

How does USFWS enforce Indian identity law in art attribution cases?

USFWS investigators pull marketplace ledgers, secure signature images, and route forensic analysis through its National Forensics Laboratory. The Luiseño tribal identity claim places the case inside DOI statute governance and DOJ prosecution ownership.

What happens when state fraud charges run parallel to federal tribal identity enforcement?

Investigations overlap. They do not merge. State counts file in district courts like the Fourth Judicial District Court of New Mexico. Federal identity counts file in U.S. District Court if DOJ prosecutors open the federal file. Parallel lanes keep liability active.

Are payment processors treated as neutral or evidentiary in art fraud affidavits?

They are evidentiary because they tie digital attribution listings to buyer payment records. When part of an affidavit, PayPal, Stripe, and bank transfer records serve as institutional proof, not marketing history.

How does the Indian Arts and Crafts Board log and escalate art identity complaints?

Complaints are archived under DOI governance. Once logged, the board routes proof to enforcement agencies like USFWS and DOJ. The board owns statute governance, not prosecution decisions.

When signatures mismatch in tribal art, which institutions control the evidentiary record?

Control sits with forensic labs, courts, and DOJ prosecutors. Galleries supply exemplars, platforms supply listing proof, payment processors tie transactions, and courts archive forensic divergence into affidavits.

Who owns prosecution decisions when Indian-attributed art fraud crosses state lines?

The U.S. Department of Justice owns prosecution decisions. The Department of the Interior owns the statute governance layer. State attorney general offices support state fraud counts. The platforms and labs support proof. DOJ owns liability decisions.

Fritz Scholder art fraud, Indian art forgery, Indian Arts and Crafts Act, eBay evidence, DOJ prosecution, consignment liability, USFWS forensic lab