An Evergreen Legal–Forensic Examination for the General Reader

Some criminal cases become infamous because of their brutality. Others linger because they expose deeper structural weaknesses: gaps between agencies, blind spots around vulnerable people, or missed signals that, in hindsight, seem painfully clear. The case of Dennis Nilsen falls squarely into that second category. What makes this timeline so disturbing isn’t only what he did—it’s how long he managed to do it without anyone noticing, and what that silence revealed about policing and social systems in late-20th-century Britain.

Revisiting this timeline through a legal and investigative lens helps illuminate why the case still appears in criminology courses, policing reviews, and discussions about victim protection. It isn’t about rehashing grisly details. It’s about understanding how one man exploited isolation, institutional gaps, and the vulnerabilities of those who rarely appeared in official records.

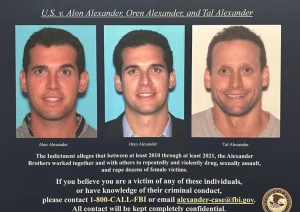

An archival police photograph of Dennis Nilsen associated with one of the most significant UK criminal cases of the late 20th century

Early Life and the Formation of Isolation (1945–1968)

Dennis Nilsen was born on 23 November 1945 in Fraserburgh, a fishing town where isolation could wrap itself around a family during the long northern winters. Those who later examined his history noted early emotional detachment and the kind of quiet inwardness that often appears in psychological assessments of offenders with long-term social withdrawal.

At 15, he left school and eventually joined the Army Catering Corps, learning discipline and structure. Yet structured environments do not always resolve ingrained loneliness. After nearly a decade in uniform, he left military service and drifted through short-term roles, including a brief stint as a Metropolitan Police trainee. He moved on quickly. Stability remained elusive.

A New Life in London—But Not a Connected One (1970–1978)

By the early 1970s, Nilsen had settled into a job at a Kentish Town jobcentre, the sort of role that offers routine but little community. London is a city where a person can vanish in plain sight, especially in the 1970s—an era before coordinated databases, CCTV networks, or modern vulnerability assessments. Friends came and went. Housing arrangements shifted. Nothing tied him tightly to other people.

These were the years in which his fantasies began to harden into something more dangerous. Criminologists sometimes describe this as the “bridging period,” when internal narratives start to replace functional coping mechanisms. The fantasies didn’t erupt suddenly—they simply filled the empty spaces where real connection should have been.

Melrose Avenue: The Murders Begin (1978–1981)

In December 1978, inside a nondescript semi-detached house at 195 Melrose Avenue, Nilsen carried out what investigators later recognised as his first murder. Many of the men he targeted were transient or struggling with homelessness—groups that historically receive limited attention in missing-persons systems. When these individuals went missing, there was often no family member waiting to raise the alarm, and authorities lacked the modern cross-force databases that today help track vulnerable adults.

Between 1979 and 1981, multiple murders took place inside the Melrose Avenue property. Nilsen disposed of remains using methods that exploited the privacy of the home and the absence of early forensic technologies. Neighbours sometimes reported unpleasant smells or unusual smoke, but without any overriding cause for suspicion, no deeper investigation followed.

Legal analysts often point to these years when discussing why offenders sometimes avoid detection for so long. Without digital records, formal risk assessments, or centralised missing-persons reporting, the disappearance of vulnerable individuals rarely escalated in urgency.

Cranley Gardens: A New Flat—and a Path to Discovery (1981–1983)

In the autumn of 1981, Nilsen moved to a top-floor flat at 23 Cranley Gardens in Muswell Hill. The move placed him in an environment that would eventually expose him. Unlike his former home, the new flat had no garden, no private space to conceal evidence. Modern policing studies often highlight how offenders adapt or escalate in response to environmental pressures, and Nilsen was no exception.

From 1981 into early 1983, several more murders occurred inside the cramped flat. With no access to outdoor disposal, he attempted to rid himself of remains through the property’s plumbing system. This method, grotesque as it was, created the first traceable sign that something was catastrophically wrong.

The Break in the Case (February 1983)

The turning point came on 8 February 1983, when a routine call to clear a blocked drain revealed material that specialists quickly identified as human remains. This discovery is frequently referenced in investigative training as an example of how major cases can emerge from ordinary incidents.

When detectives arrived at the flat on 9 February, Nilsen did something few predicted: he spoke openly. Not in an emotional panic, but calmly, describing what he had done as though recounting mundane events. His voluntary disclosure shaped the structure of the investigation that followed. Interview teams documented his statements carefully, following the procedures available at the time—procedures that have since evolved, in part due to lessons from cases like this.

Reconstructing the Case Without the Victims’ Histories (1983)

One of the greatest challenges investigators faced in 1983 was identifying the victims themselves. Many had no stable address. Some had no formal employment records. Several had never been reported missing at all. Without the forensic DNA resources available today, investigators relied on dental comparisons, anthropological assessments, and any surviving personal effects.

Policing experts often highlight the Nilsen case when explaining why the UK later developed stronger systems for monitoring vulnerable adults and improving inter-agency communication. The case demonstrated how easily people can vanish when no system is designed to look for them.

Preparing for the Old Bailey: A Legal Examination of Responsibility (1983)

As the case moved toward trial, prosecutors needed to determine how to frame Nilsen’s actions under the law. The central issue became criminal responsibility—a cornerstone of murder prosecutions. The defence argued diminished responsibility, referencing psychiatric assessments that described his detachment from normal emotional functioning. The prosecution countered with evidence of planning, concealment, and pattern consistency.

Courts in England and Wales assess diminished responsibility under the Homicide Act 1957, as amended by the Coroners and Justice Act 2009. Though these amendments came later, the principles—whether an abnormality of mental functioning substantially impaired judgment—remained relevant. Prosecutors emphasised conduct that showed awareness and control.

The Trial and Verdict (October–November 1983)

The trial opened at the Old Bailey on 24 October 1983. Jurors were asked to consider not just what Nilsen had done but how he had done it: the methodical processes, the efforts to hide evidence, the repeated nature of the crimes. These were all factors that pointed toward intent.

On 4 November 1983, the jury found him guilty of six counts of murder and two of attempted murder. He received a life sentence, which was later converted into a whole-life tariff, a penalty reserved for offenders considered beyond rehabilitation and posing a persistent risk to public safety.

Life in Prison and Public Reflection (1983–2018)

Across the decades he spent in prison, Nilsen wrote extensively, producing journals that sometimes resurfaced in public discussions about criminal psychology. Researchers studied his behaviour not to sensationalise, but to understand the psychological underpinnings of individuals who commit serial violence while maintaining outward normality.

His incarceration also fed into broader questions about the management of long-term prisoners—especially those who age into ill health while serving whole-life terms.

Death and Renewed Scrutiny (2018)

On 12 May 2018, Nilsen died at HMP Full Sutton following complications after surgery. An inquest later recorded the causes as a pulmonary embolism and a retroperitoneal haemorrhage. His death prompted renewed discussion about transparency in whole-life imprisonment and the state’s responsibilities toward prisoners who will never be released.

A Case That Continues to Shape Forensic and Legal Thinking

The impact of the Nilsen case extends far beyond its timeline. It continues to influence several key areas of criminal justice:

1. Missing-Person Coordination

Modern systems—such as the National Crime Agency’s UK Missing Persons Unit—reflect lessons drawn from cases where vulnerable individuals vanished without urgent attention.

2. Forensic Identification Advances

Today’s ability to use DNA profiling, forensic anthropology, and digital records means unidentified victims would be far more likely to be named.

3. Interview and Confession Protocols

The PEACE interviewing model, now widely used in the UK, was shaped by cases where suspects spoke freely but required careful, structured questioning to ensure accurate, admissible evidence.

4. Understanding Offender Targeting of Vulnerable Groups

The case remains a stark reminder that those living unstable or isolated lives are at higher risk of exploitation—and that institutions must work proactively, not reactively, to safeguard them.

FAQ: How the Dennis Nilsen Case Shaped UK Criminal Investigations

Why did the police not identify many victims at the time?

Without modern databases, DNA profiling, or coordinated national systems, vulnerable men who disappeared in the 1970s and early 1980s were rarely flagged across police forces. This case is frequently cited when training officers on the complexities of victim identification.

How do modern investigators prevent cases like this from going unnoticed?

Current policing relies on shared databases, real-time missing-person alerts, and clearer vulnerability markers. These tools help ensure that individuals at risk do not disappear without triggering wider inquiries.

Did the legal system change because of the Nilsen case?

While no single reform was created solely because of this investigation, the case contributed to ongoing discussions around diminished responsibility, multi-agency communication, and forensic improvements.

Why is the Nilsen case still relevant decades later?

It continues to serve as a reference point for understanding investigative blind spots, forensic evolution, and the legal challenges surrounding offenders who hide in plain sight.

Dennis Nilsen — Key Facts

Full Name: Dennis Andrew Nilsen

Born: 23 November 1945, Fraserburgh, Scotland

Died: 12 May 2018, HMP Full Sutton (aged 72)

Status: Deceased (served a whole-life tariff)

Crimes: Murder and attempted murder of multiple men in London between 1978–1983

Victim Profile: Primarily young, vulnerable men, many experiencing homelessness or unstable housing

Locations: 195 Melrose Avenue (Cricklewood) and 23 Cranley Gardens (Muswell Hill)

Arrested: 9 February 1983

Trial: October–November 1983 at the Old Bailey

Conviction: 6 counts of murder, 2 counts of attempted murder

Sentence: Life imprisonment, later converted to a whole-life order

Why This Case Still Matters

- Highlighted failures in missing-persons coordination

- Exposed vulnerabilities in forensic identification methods of the era

- Influenced modern UK interview practices and evidence handling

- Raised awareness about risks faced by socially isolated individuals