The case gripping Arizona has left even seasoned investigators shaken — a doctor’s husband accused of watching pornography and drinking inside his home while his two-year-old daughter slowly baked to death in a car outside.

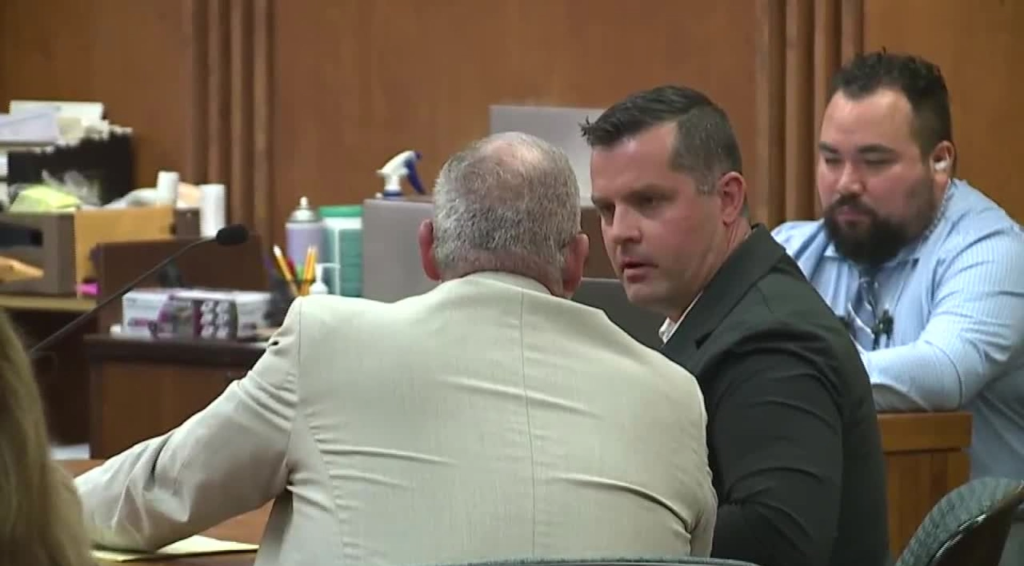

On a blistering July afternoon in 2024, 37-year-old Christopher Scholtes allegedly left his toddler, Parker, sleeping in the family’s Acura outside their home in Marana, Arizona. He told police he kept the air-conditioning running to keep her comfortable — but prosecutors say he then went inside to drink, play PlayStation, and watch explicit adult videos, forgetting his daughter was still outside.

When the car eventually shut off, Parker was trapped in the rising heat. By the time Scholtes returned, she was unresponsive. Her body temperature had soared to fatal levels, according to court documents reviewed Tuesday in Pima County Superior Court.

The doctor wife of Christopher Scholtes, 37, arrested on second degree murder charges for the hot car death of their 2-year-old, is standing by her husband.

At a pre-trial hearing this week, prosecutors argued the porn allegation helps establish Scholtes’s mindset and “gross disregard for human life.” The judge disagreed, ruling that detail too prejudicial for jurors.

However, the court did allow evidence of past incidents where Scholtes allegedly left his children in vehicles unattended. Investigators recovered text messages between Scholtes and his wife, Dr. Erika Scholtes, an anesthesiologist, showing she had previously warned him about the risks.

“This wasn’t a one-time mistake,” one prosecutor said in court. “It was a pattern.”

Christopher Scholtes is said to have been watching porn while his two year-old daughter Parker (pictured above being held by her mother Erika) died in a hot car

Despite the accusations, Dr. Scholtes has continued to publicly support her husband, saying he is not a monster but a grieving father who made a tragic error.

Friends told local reporters she remains “heartbroken but loyal,” describing a family torn apart by loss and legal warfare.

A hot car death occurs when a child or pet dies after being left inside a vehicle that becomes dangerously hot. Even with mild weather, the inside of a car can reach over 120°F (49°C) within minutes, leading to heatstroke and organ failure.

According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), an average of 37 children die in hot cars every year in the U.S. — most after being accidentally left behind by parents who become distracted or assume someone else removed the child.

The Scholtes case echoes several high-profile U.S. prosecutions involving hot car deaths — including Georgia father Justin Ross Harris, who was convicted in 2016 of leaving his 22-month-old son to die in similar circumstances.

Psychologists say these cases tap into a specific kind of parental denial and routine-driven amnesia, where adults underestimate how easily a lapse in attention can turn deadly.

Scholtes has pleaded not guilty to first-degree murder. If convicted, he faces life imprisonment without parole.

Dr. Scholtes continues to work in Tucson, though she has taken leave from the hospital periodically since her daughter’s death. The couple’s home remains a site of quiet grief — a small pink memorial of toys and flowers still stands by the driveway where Parker last slept.

Jury selection is expected to begin later this year. Prosecutors plan to argue that Scholtes’s actions show reckless indifference, while defense attorneys are expected to claim accidental negligence, not malice.

Outside court, local advocates renewed calls for federal legislation mandating child detection sensors in vehicles — technology capable of alerting drivers if a child remains inside after the engine shuts off.

If convicted, Christopher Scholtes faces the harshest penalties Arizona law allows. Prosecutors have charged him with first-degree murder, a Class 1 felony under Arizona Revised Statutes §13-1105, which applies when a person causes another’s death with premeditation or through acts showing “extreme indifference to human life.”

In plain terms, first-degree murder in Arizona means the accused knew their actions could kill and acted with reckless disregard anyway. The offense carries a mandatory life sentence, and in some cases, the death penalty—though prosecutors have not said whether they’ll pursue that option.

Defense attorneys, meanwhile, are expected to argue for a lesser charge such as criminally negligent homicide or manslaughter, both of which acknowledge reckless behavior without intent to kill. Under Arizona law, those offenses can still lead to five to twenty-five years in prison, depending on aggravating factors like alcohol use, prior conduct, and whether the victim was a minor.

“The difference between murder and negligence in Arizona often hinges on state of mind,” explained Tucson defense attorney Michael Grantham, who isn’t connected to the case. “If the jury believes the father truly lost track of time, that’s negligence — but if they think he knew the risks and ignored them, that’s murder.”

In addition to the criminal trial, the Scholtes family could also face civil consequences. Under Arizona personal injury and wrongful death law, the estate of a deceased child may bring claims for damages, including pain and suffering, emotional distress, and punitive compensation. These civil actions are separate from criminal prosecution but often follow in cases of parental negligence or recklessness.

Why do hot car deaths keep happening?

Hot car deaths occur when children are accidentally left inside vehicles that overheat. Within just 10 minutes, the internal temperature can climb by 20 degrees or more, even if windows are slightly open. Most cases happen because of human error — stress, multitasking, or false memory — rather than intentional harm.

Whether the court sees Christopher Scholtes as a careless parent or a calculating killer, one fact is undeniable: a two-year-old girl suffered a slow, silent death just steps from her father’s living room.

And as his trial looms, the question facing Arizona — and the nation — remains chillingly simple: how many more children must die before technology and accountability catch up to human negligence?