Some questions refuse to settle quietly, even after decades of research. The nature-versus-nurture debate around serial killers is one of them. Whenever society encounters someone who commits repeated acts of violence, the same uneasy thought resurfaces: Was something already broken inside this person from birth… or did life twist them into what they became?

It’s not just a philosophical puzzle. Understanding the drivers of extreme violence influences everything from early-childhood policy to criminal profiling, mental-health intervention, and public safety. And yet, the closer researchers look, the less the answer fits into a tidy binary.

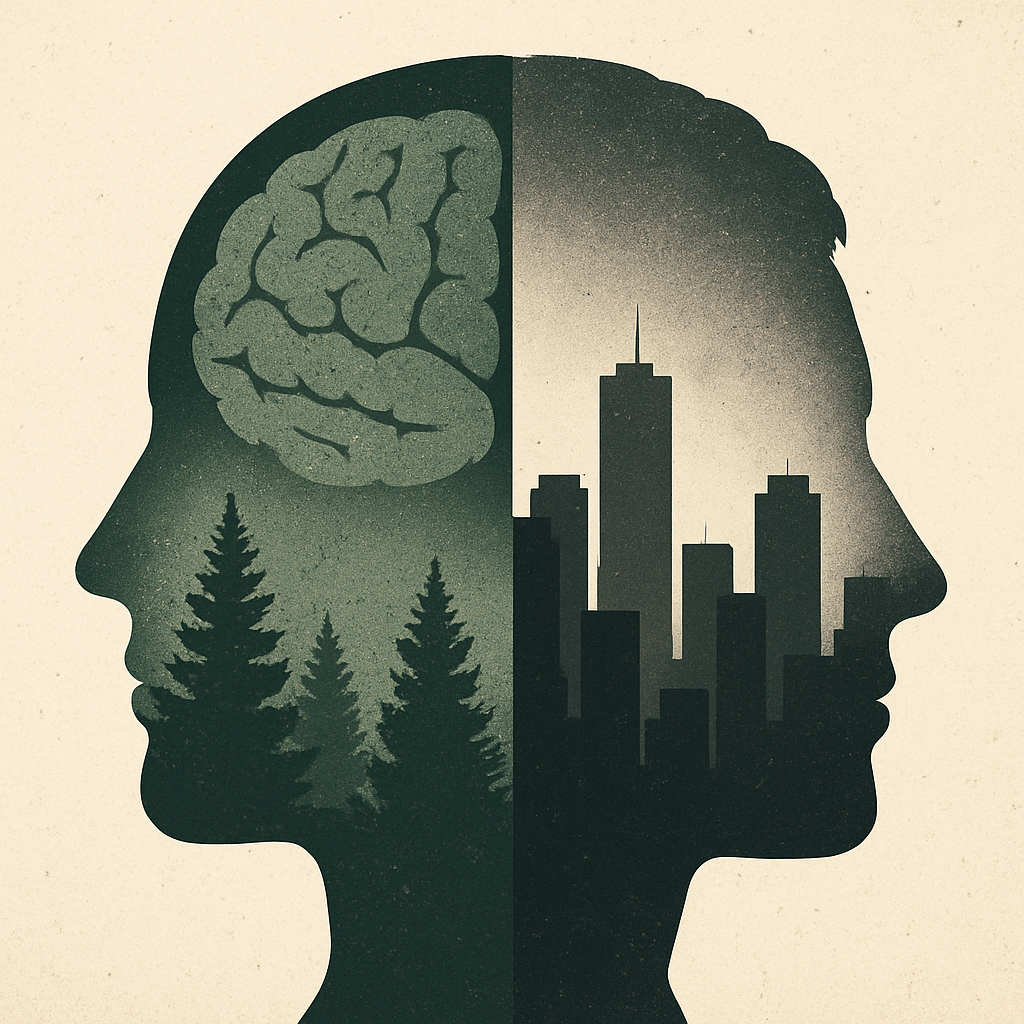

Today’s most respected neuroscientists, psychologists, criminologists, and behavioural researchers largely agree: serial killers emerge from interactions, not absolutes. It’s the meeting point of biology, environment, and psychology that determines how a vulnerable mind develops—and whether it steers toward empathy or destruction.

This piece brings together the strongest current evidence, explained in clear, human language for a general reader, without sensationalism or case-reenactments.

No credible scientist believes a “serial killer gene” predetermines violence. But research does identify biological risk factors—traits that can tilt someone toward aggression or emotional detachment under certain circumstances.

Studies in behavioural genetics point repeatedly to the same theme: genes set the range of someone’s emotional responses, but environment decides how far they travel within that range.

For example:

MAOA variants (popularly known as the “warrior gene”) have been linked in peer-reviewed research to heightened stress reactivity and difficulty regulating anger when paired with childhood trauma.

Large twin studies published in journals such as Psychiatry Research and The Lancet suggest that antisocial traits have a heritable component—but only account for part of the risk.

Genes shape temperament, but they don’t write destiny.

Modern neuroimaging has revealed notable patterns in individuals with long histories of violent behaviour:

Reduced prefrontal cortex activity

This region governs planning, empathy, restraint, and moral decision-making. Lower activity can impair judgment and weaken a person’s ability to inhibit harmful impulses.

Abnormalities in the amygdala

The amygdala helps process fear and emotional cues. Reduced volume or responsiveness is associated with blunted empathy and difficulty recognising distress in others.

Differences in emotional reward pathways

Some offenders show altered patterns in brain regions linked to pleasure, suggesting that excitement, dominance, or control may be processed differently.

These findings never operate alone. Neurologists emphasise that structural differences increase susceptibility—not inevitability.

Psychologists studying antisocial behaviour often highlight traits like:

chronic impulsivity

shallow emotional responses

manipulative tendencies

limited capacity for guilt

low sensitivity to punishment

Research from the American Psychological Association shows that elevated psychopathic traits correlate with an increased risk of violent offending, but the vast majority of people with these traits do not become serial killers. Many function normally in society.

That nuance is essential: personality traits can create vulnerability, but they need environmental triggers to take a destructive shape.

While biology sets the stage, environment often determines the script. Decades of criminology research find that many violent offenders share a cluster of early-life experiences collectively known as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs).

ACEs include:

physical or emotional abuse

neglect

unstable, inconsistent caregivers

exposure to domestic violence

chronic humiliation or bullying

household substance misuse

Long-running studies from the CDC and Kaiser Permanente show that high ACE scores dramatically increase the likelihood of adult aggression, substance abuse, and emotional dysregulation.

When children lack stable attachment figures, their brains adapt to survive—often at the cost of empathy, trust, and self-control.

Isolation is another strong risk factor. Children who experience chronic rejection or a sense of “outsiderness” may begin to retreat into fantasy worlds where power and control replace connection and belonging. Left unchecked, these fantasy patterns can crystallise into harmful behaviours.

Researchers from the University of Cambridge have documented how loneliness, humiliation, and lack of healthy peer bonds can amplify antisocial traits, especially in children already dealing with biological vulnerabilities.

The most dangerous trajectory appears when:

a child has a biological predisposition toward low empathy or high impulsivity

and

grows up in an environment marked by trauma, instability, or emotional deprivation

Neither factor alone predicts violent behaviour. Together, they significantly magnify risk.

Some violent offenders report that harming others feels compulsive or relieving. Modern psychology offers several explanations:

People raised in chaotic environments often fail to develop healthy coping skills. Violence can become a maladaptive way to manage shame, rage, or powerlessness.

Victims of severe early trauma may learn to detach emotionally during distress. In extreme cases, this detachment may resurface during violent acts, creating a sense of “watching from the outside.”

British serial killer Dennis Nilsen described this kind of dissociative split in multiple interviews, explaining that he often felt as though he were observing himself rather than acting with conscious intent. Criminologists frequently reference his case to illustrate how emotional detachment, loneliness, and fragmented identity can interact in dangerous ways when early trauma goes untreated.

If an initial act of harm produces relief or excitement, the brain’s reward system may begin reinforcing the behaviour—much like an addiction.

Some individuals build inner worlds where dominance or violence becomes central to their sense of self. Over time, fantasy and reality blur.

These explanations don’t excuse actions—but they do help experts understand how certain behavioural patterns form and why they’re so difficult to interrupt.

The most credible researchers now view serial offending through a risk-accumulation model:

Biology provides vulnerability

Environment shapes development

Psychology interprets experience

Opportunity allows behaviour to occur

Remove any one factor, and the trajectory might shift entirely.

Instead of asking whether serial killers are born or made, a more accurate question is:

How do biological sensitivity and life experience interact to create extreme violence in a small subset of people?

This framing aligns with current academic consensus from bodies such as:

the American Psychological Association (APA)

the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)

leading criminology programmes at the University of Cambridge and John Jay College

These organisations emphasise prevention—not prediction.

While no model can predict individual behaviour, large-scale data gives clear guidance on reducing risk across populations.

Consistent caregivers, safe housing, and predictable routines build emotional resilience.

Children who experience violence or neglect benefit enormously from therapy, mentorship, and long-term community support.

Positive relationships reduce isolation, one of the strongest risk multipliers for antisocial behaviour.

Access to diagnosis and support for conduct disorders, attachment difficulties, and emotional dysregulation lowers long-term risk.

Communities with strong social services, stable schooling, and accessible youth programmes experience significantly lower rates of violent crime.

The biggest prevention wins come from helping children long before they reach adolescence.

Serial killers don’t emerge from a single cause, a single moment, or a single gene. They arise from a web of biological sensitivities, environmental hardships, psychological patterns, and missed opportunities for intervention.

Understanding that complexity doesn’t excuse violence—far from it. It highlights the responsibility societies carry to support vulnerable children, strengthen communities, and recognise early warning signs before they harden into lifelong patterns.

The nature-versus-nurture question may never have a perfect answer, but the research points to something hopeful: changing a child’s environment can often change their entire future.

No single gene causes violent behaviour. Some genetic traits influence temperament, impulse control, or stress reactivity, but environment determines whether those traits become dangerous.

Yes—especially when trauma occurs repeatedly or without supportive caregivers. However, most people with traumatic backgrounds do not become violent.

No. Researchers can identify risk factors, but prediction of individual behaviour is impossible. Prevention focuses on improving environments, not labelling children.

Absolutely not. Psychopathy exists on a spectrum, and most people with elevated traits live normal, non-violent lives.

A combination of early trauma, lack of emotional support, and pre-existing biological vulnerabilities. None of these alone create violent offenders.