Understand Your Rights. Solve Your Legal Problems

Since it first became widespread last October, #MeToo has been widely adopted by millions of Twitter users. Hina Belitz is an author and specialist employment lawyer at Excello Law, and below she explains the overall impact of the #MeToo movement and explores the implementation of workplace sexual harassment policies.

Its endurance shows that the hashtag is much more than a temporary social media phenomenon. Instead, it has become symbolic of a worldwide movement against sexual harassment and assault which is designed to produce permanent change in how men treat women. This is particularly important in the workplace, where #MeToo has developed a special significance because that is where many of the problems occur.

Harvey Weinstein will go down in history as the #MeToo catalyst: scores of actresses on both sides of the Atlantic have documented their personal traumatic experiences of his alleged abuse. The criminal activities of men such as Weinstein, and other prominent figures who have misused their positons of power, has thrown a spotlight on the issue. The international use of #MeToo not only highlights the global prevalence of sexual harassment, it has also enabled voices that were previously silent to be heard.

The risks of being lenient about the problem are manifestly apparent to many companies. As a result, they have become proactive in putting measures in place to prevent it arising, where possible, and to take swift action when it does. This is perhaps best demonstrated by Netflix. A new sexual harassment policy for the company’s staff, including a five second time limit when looking at another employee. To look for any longer is deemed creepy and inappropriate.

Although it is based on good intentions, the introduction of a no staring policy cannot easily work in practice because it is almost impossible, legally, to prove how long one person is staring at another. Netflix has introduced a further preventative policy: employees are not allowed to ask co-workers for their mobile phone numbers. This seems equally unworkable given that such a request is commonplace among members of a working group or team in many organisations.

The critical question with each policy is one of context and degree. For example, staring into space when someone happens to be within your line of vision cannot be regarded as harassment, although a permanent fixed stare could well be. Beyond harassment, habitual staring might be seen as intimidation or bullying.

Equally, repeated and persistent requests for a colleague’s mobile number could be construed as harassment. But a casual “what’s your number” request happens every day in almost every business as co-workers ask the question without a hint of harassment. Making a subsequent complaint to an HR manager about it indicating that someone has asked for your number is very unlikely to viewed a serious transgression by any organisation.

In summary, the Netflix policies are neither reasonable nor workable because the spirit of the law risks being lost in the formulaic nature of the new rules. We have been here before. Similar approaches have failed previously, such as when flexible working rules were over prescriptive and when grievances had to set out in writing at a particular time and in a particular way in order to be valid. Such formulaic prescriptions can lead to unfair loopholes and absurd complaints such as timing the length of a stare. The idea is not to micromanage staff behaviour, but to train them to understand the objective of the law and acts that may fall outside it.

The Netflix policy examples are a very long way removed from the criminal acts allegedly committed by Weinstein. How companies act to prevent such behaviour, or something which might lead to it, and how they should respond must be both proportionate and pragmatic. Overreacting to events or virtue signalling does little to serve the interests of a company’s employees. The new Netflix policies have, according to reports, significantly disrupted production on its House of Cards programme, where actors who spend many hours on set together can no longer look at each other, except briefly, or hug each other – as actors often do.

To a degree, the policies potentially undermine the serious nature of the #MeToo hashtag which has dramatically shaped the national discourse – and rightly so. At a time when it is imperative that companies adopt and maintain compliant sexual harassment policies, making sure that they are feasible and sensible is equally important.

In determining whether looking at someone or requesting their number constitutes something approaching sexual harassment or assault, the behaviour would need to be serious, sustained, or both. When applying the law and deciding what is appropriate for each business, all employees certainly need to be familiar with harassment-free employment policies.

But to allow such policies to work in practice, they also need to be reasonable and sensible in countering behaviour that is clearly inappropriate. No matter how comprehensive or well-drafted the scope and impact of sound employment policies may be, they can only go so far in endeavouring to shape the nature of how each individual chooses to behave. Ultimately, personal conduct cannot be wholly determined by rulebooks, but rather by common courtesy, mutual respect and plenty of common sense.

The NRA has not commented publicly on the issue.

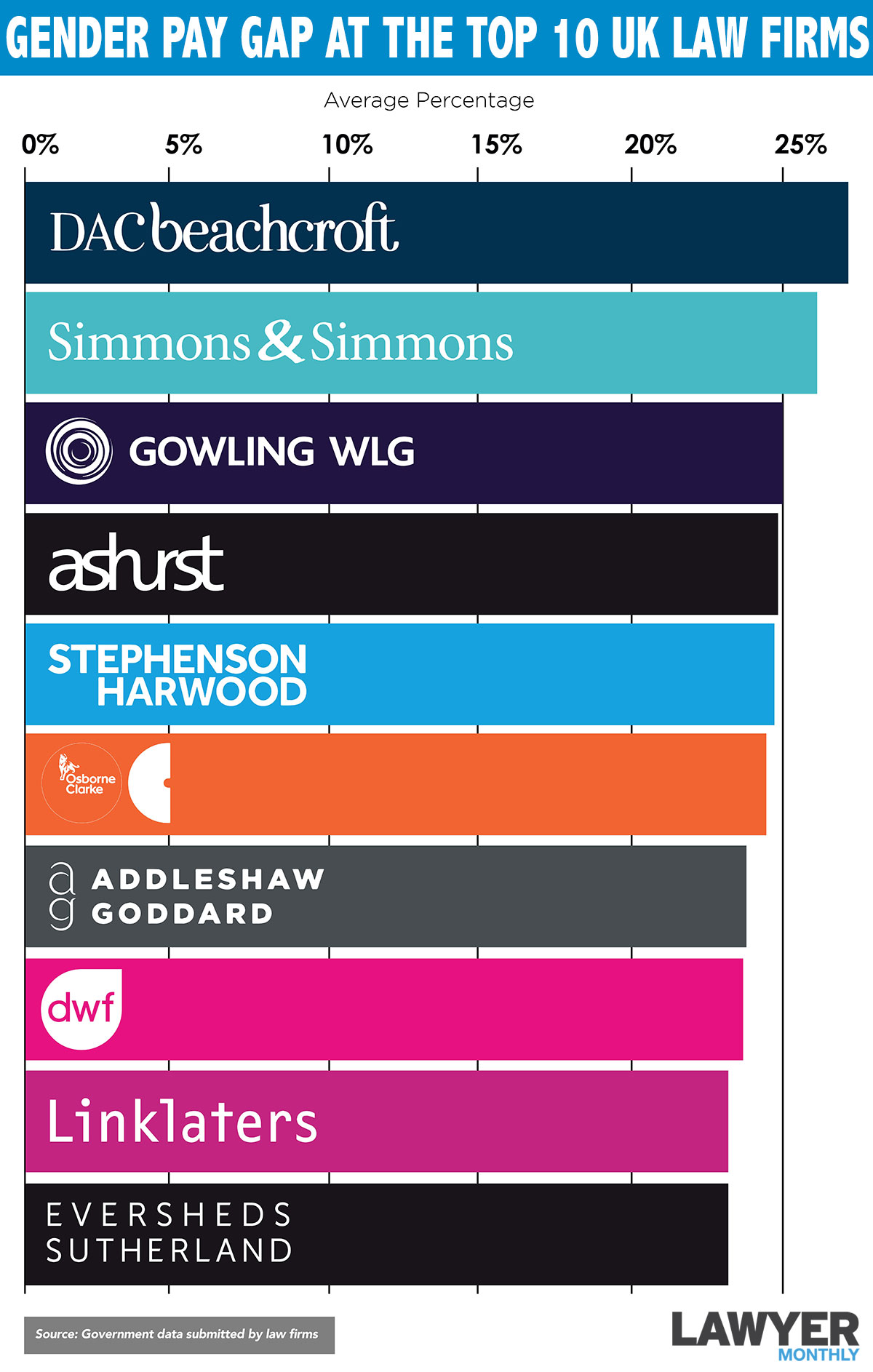

This month, in a special Lawyer Monthly feature we decided to take a look into the surprising reports around the gender pay gap. Even though most suspected a level of disparity, no one had really quite predicted the sheer gap between both genders and how there is still such a way to go until women are given the same opportunities as men.

The legal industry, of course, was not exempt from this. So, what is next? We know that it is a widespread problem, but what are law firms doing about the issue?

We spoke with two of the top 100 UK law firms on this report and the steps they are taking to tackling the gender gap problem.

The Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United US once stated: "Women belong in all places where decisions are being made... It shouldn't be that women are the exception”; such a quote remains true in all areas, even the modern workplace.

Earlier this year, companies in Britain had to report details regarding the pay gap between genders and unsurprising for some, yet a shock to others, the results presented quite a disparity between men and women.

The figures had revealed that if you are a woman working at a large UK firm, you are on average more likely to be paid less than men, with 78% of companies paying men more. A contributing factor towards this is due to the fact men tend to be hired for higher paid roles and are paid higher bonuses than their female counterparts.

The legal industry also portrayed such bias and criticism. When reports began to sift through, the results did not seem so bad. The average gender pay gap for the 25 largest UK firms (by revenue) was at 20%[1]. The firm’s median pay gaps[2] were higher than the mean pay gaps; some of the highest mean gender pay gaps were: Lathan & Watkins at 39.1%, Wei Gotshal at 38.1% and Kirkland & Ellis at 33.2%. The lowest mean gap included Forsters at 2.3% and Irwin Mitchel at 12.8%.

These reports sparked controversy, however, as many law firms were criticised for excluding partners from their pay gap reporting; with the Equality Act 2010 Regulations stating that firms need to release the statistics of employee’s pay, many big firms excluded partners with their reason being due to the fact that equity partners are not ‘salaried employees’. Many expressed this was unfair as it kept secret the most senior, well-paid and mostly-male lawyers.

A level of transparency was needed and some top firms, such as Clifford Chance knew this. Laura King, the firm’s global Head of People and Talent stated: “Unless you’re transparent you don’t really understand what’s going on in your organisation. Excluding partners, we felt would not give us the opportunity to examine ourselves."

This transparency had shown that Clifford Chance had reported a mean pay gap of 66.3%; other firms inclusive of partners, Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, reported a mean pay gap of 60.4%; Linklaters posted 60.3%; and, Slaughter and May reported 61.8%.

From this, some law firms buckled under the pressure and showcased the statistics of all employees.

What are the reasons behind this disparity and what can be done? We hear from two of the UK’s Top 100 law firms: Keystone Law and Holman Fenwick Willan (HFW)* who speak on what they are doing to tackle the gender pay gap.

Problem: Male Domination

There are several reasons up for debate here. One of the main reasons behind women being paid, on average, less than men, is the fact that there are more male partners than female.

From a study conducted by the SRA in August 2017, they found that women make up 48% of all lawyers in law firms (and 47% of the UK workforce). Seniority made more a difference, however, with women making up 59% of non-partner solicitors and the larger law firms (with 50 plus partners), showing women make up 29% of partners.

Even Slaughter & May had highlighted that their gap is widened significantly due to the all-female secretarial positions.

Solution:

A spokesperson at Keystone Law, one of the UK’s Top 100 law firms, stated: “Many firms claim to have a diversity plan in place but invariably it’s more talk than action. What really makes an impact is truly recognising talent and showcasing ability.”

Keystone Law is not a traditional law firm, having chosen to go against the grain by eradicating the partnership model, in favour of a flat structure for all fee earners who have almost all been partners at some of the country’s leading law firms. All Keystone lawyers come on board at the same level and hold the same title. Of the lawyers Keystone currently engages 40% of them, are female. This stands in stark contrast to 18% of partners at Top 10 firms, as cited by PwC's Law Firm Survey 2017.

HFW said: “Ensuring higher levels of female representation at the highest levels of the industry, particularly among partnerships, has been high on the law firm agenda for years, but we need action, not words. More firms should set defined targets, as we have, and be more proactive.”

Steps they have already taken (as part of our gender equality action plan) include:

They expanded: “The percentage of female fixed-share partners at the firm has increased from 12% in 2015 to 26% today, while women account for 50% of our new Legal Director roles. Over 40% of the firm's internal partner and legal director promotions over the last two years were women.”

At the lower end of the pay scale, there are significant issues of gender stereotyping. The vast majority of secretarial services staff – not just in the legal industry, but more generally – are women, for example.

Commenting on the matter, HFW said: “This is harder to resolve. A law firm would currently find it challenging to achieve gender equality in that role due to a lack of male applicants. It is possible that law firms could visit schools to provide students with a broader outlook on future careers and we can adapt how we speak about secretarial roles so that they are attractive to men as well as women. This will be a longer-term challenge.”

Problem: Not enough law students?

UK law student figures show that 67% of applicants in 2016/2017 were female. We asked HFW: Will this ultimately lead to a redressing of the balance, or do you think law schools have a continued responsibility to enrol more females?

“This is not a new phenomenon – there have been high levels of female lawyers coming into the profession for a relatively long time. It is important that law schools maintain a strong pipeline of male and female graduates, but this alone will not redress the balance.”

Solution:

Going back to problem number one, HFW suggested: “Law firms must take proactive steps to encourage and enable more female lawyers to step into more senior roles.”

Problem: Women have a parental responsibility

The imbalance of men and women in the legal sector is often said to be due to parental responsibilities, which traditionally lie with women. We ponder on the thought that law firms need to offer solutions that will help re-dress the balance and thus the perception of the sector, (i.e. flexible working hours, allowing male staff to take on more parental responsibilities and part-time working for male staff).

“Because of their perceived reliability and stability, husbands and fathers in the workplace are often more likely to be given pay increases and promotions. Unfortunately, the opposite still seems to be true for women with children, whether they are married or not! The sector therefore needs to concentrate its efforts on removing any stigma that is attached to mothers as well as fathers who require flexibility and agility in order to look after their families”, replied Keystone.

Solution:

With Keystone’s business model allowing lawyers to work on their own terms (including earnings), they state: “Many of the reasons women, in particular, cite for being driven out of the legal profession are absent from the Keystone model. There are no set billing targets, lawyers can work from any location that they choose and work the hours that best suit them. This works towards re-dressing the balance of parental responsibilities as both men and women can tailor their practice to suit them - without worrying about being penalised for requiring flexibility.”

“Interestingly the shift towards the desire for greater flexibility is increasingly stemming from millennials. According to a recent Deloitte report, up and coming lawyers are increasingly being inspired by the growing gig economy, realising that earning well doesn’t need to involve being chained to a desk during fixed hours. Not only that, these young lawyers are rebelling to demand a better balance — and influencing those more senior to them in the process!”

HFW have a similar solution at hand: “We offer flexible working hours to all fee-earners, male and female, and also offer extremely generous shared parental leave to male employees at a rate well above the statutory requirement. But the industry could do more, such as lobbying government to come up with practical and pragmatic solutions that will encourage a societal change to parental responsibilities. We are keen to work with others in the sector to progress this.”

Problem: Do clients prefer male lawyers?

It has been suggested that this is a client level problem, being that clients may prefer male representation. Is this true?

HFW commented: “We disagree. Gender diversity, and diversity more generally, is an issue that clients now take incredibly seriously. Clients are increasingly asking law firms for diversity and inclusion data as part of the pitch process.”

Solution:

If you don't have a diverse team, the chances are that you won't win the work. The problem is with the law firms, and we can achieve more by working together with our clients on this issue.

Problem: Are there enough female law students?

Short answer: Yes. UK law student figures show that 67% of applicants in 2016/2017 were female. Could this ultimately lead to a redressing of the balance, or do law schools have a continued responsibility to enrol more females?

HFW said: “It is important that law schools maintain a strong pipeline of male and female graduates, but this alone will not redress the balance.

Solution:

“Law firms must take proactive steps to encourage and enable more female lawyers to step into more senior roles.”

Since the reports, there has been a surge of motivation to ensure the gap is narrowed. Whether is it the attitudes towards women in the legal workplace needing to change, or the traditional working models for our contemporary lawyers, there will be a strong push towards equality, which will, without doubt, change the legal sphere in the future.

*Based on revenue, Keystone is currently ranked 94 and HFW is at 28, according to The Lawyer

[1] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-04-16/hidden-gender-london-law-firms-are-divided-over-true-pay-gap

[2] https://www.legalcheek.com/2018/04/deadline-for-gender-pay-gap-reporting-is-today-heres-how-law-firms-have-done/

From the creators of Europe’s biggest women in tech conferences, Women in Law Summit is a groundbreaking new conference for women in the legal industry.

Through inspirational keynotes, engaging panel discussions on pivotal industry challenges, and interactive career development workshops, this conference provides all the content and networking opportunities you need to flourish in the sector.

Gain all the actionable insight you need to supercharge your career… let’s break new ground in the world of law!

SAVE 15% ON YOUR TICKETS WITH LAWYER MONTHLY. BUY TICKETS HERE AND QUOTE LMONTHLY15

Confirmed speakers currently include:

Gina Miller, Founder of SCMDirect and the True and Fair Foundation

Dame Justine Thornton DBE, High Court Judge at Queen's Bench Division (QBD)

Dana Denis-Smith, Founder of First 100 Years

Grace Ononiwu OBE, Chief Crown Prosecutor for the West Midlands Crown Prosecution Service

Helen Libson, Global Community Manager for Peerpoint by Allen & Overy at Peerpoin

Elisabeth Sullivan, Senior legal counsel at Sasol UK Limited

Miriam González Durántez, Founder of Inspiring Girls

Alexandra Gladwell, Senior Commercial Litigation Lawyer and Peerpoint Consultant at Peerpoint

Jenifer Swallow, General counsel at TransferWise

Melanie Carter, Head of the Public & Regulatory Law Department at Bates Wells Braithwaite

…. and many more!

We will provide all the content and networking opportunities needed to boost your skills and supercharge your career, whilst addressing how to close the gender gap.

See full speaker list.

Request a brochure for all the info on the conference’s format, speakers and prices.

Check out our latest Women of Silicon Valley Promo 2019: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P55L0U875T8

Have we reached a tipping point for legislating for anonymity for suspects pre-charge? David Malone - a prominent human rights and criminal barrister specialising in the field of sexual violence and victims’ rights - speaks on the never-ending debate of whether defendants should be named and 'shamed' prior to being officially charged. In this insightful article, he touches on the recent Cliff Richard case: Sir Cliff Richard v BBC and South Yorkshire Police.

Have we reached a tipping point for legislating for anonymity for suspects pre-charge?

Recent events on the journey

As the heat and light surrounding the Cliff Richard case [Sir Cliff Richard v BBC and South Yorkshire Police] fades, one ember steadfastly maintains its glow: isn’t it now time for the Government to legislate and grant anonymity for suspects pre-charge? Or, as Anna Soubry MP put it at Prime Minister’s Questions on the actual day the judgment was released, is it now time for ‘Cliff’s Law’ - a law preventing the media naming suspects before they are charged in relation to any offence, not just rape?

The Prime Minister, who eluded to the fact she had considered the issue as Home Secretary, appeared to reject the idea stating, “there may well be cases where actually the publication of a name enables other victims to come forward and therefore strengthen the case against an individual”. Moreover, it was a matter for “careful judgment” to be exercised on the part of the police and the media.

That “careful judgment” was found to be lacking by Mr Justice Mann on the part of the police and the BBC in Sir Cliff’s case. Indeed, before the trial, the police had already admitted liability and agreed to pay Sir Cliff substantial damages in the sum of £400,000, plus costs. The fight for the police at trial was not with Sir Cliff, but with the BBC, a battle they won when the judge found the police did not merely volunteer information regarding the investigation for its own purposes; it provided it because of a concern that if it did not do so there would be a prior publication by the BBC.

As regards the BBC, the judge found that Sir Cliff had privacy rights in respect of the police investigation and that the BBC infringed those rights without legal justification. Further, that it did so in a serious way and also in a somewhat sensationalist way. The judge rejected the BBC’s case that it was justified in reporting as it did under its rights to freedom of expression and freedom of the press.

Whilst Mr. Justice Mann has acknowledged the very significant public interest in the fact of police investigations into historic sex abuse, including the fact that those investigations are pursued against those in public life, he has ruled that, “the public interest in identifying those persons does not, in my view, exist in this case”. He added, “If I am wrong about that, it is not very weighty and is heavily outweighed by the seriousness of the invasion”.

In other words, this case is not a precedent which prevents the reporting of names, even the names of so-called ‘stars’, prior to police charge – this was very much a case that turned on its stark and regrettable facts.

Notably, in their final submissions, the BBC did not even argue the possibility that reporting on the search would or might encourage other victims to come forward, the very argument advanced by Mrs May at her PMQs.

This appears at first glance a strange omission, but clearly the evidence in Sir Cliff’s case did not support it being relied upon in the final analysis by the BBC’s own legal team. Add to that the point that the police did not fight the case and it just goes to show how, in reality, factually weak the BBC’s case was.

The fact that Sir Cliff’s case was a ‘case specific’ judgment was immediately recognised by Ms. Soubry who saw it as a moment to resurrect her ill-fated 2010 Private Members Bill on the topic.

That Private Members Bill makes it expressly clear that anonymity should be controlled by the judiciary under the strict terms of the proposed Act, namely, it shall be in the interests of justice for a Judge to allow the identification of an individual where: (a) it may lead to additional complainants coming forward; (b) it may lead to information that assists the investigation of the offence; (c) it may lead to information that assists the arrested person; or (d) the conduct of the arrested person’s defence at trial is likely to be substantially prejudiced if the direction is not given.

So, have we reached tipping point?

In order to assess that question we really need to step back from the Cliff Edge and look at how we got here…

The journey to the Cliff Edge - a brief history of anonymity in sexual offence cases

The Heilbron Committee Report in 1975 [‘Heilbron’ - led by the formidable Dame Rose Heilbron DBE QC one of the outstanding defence barristers of any generation] introduced the principle of anonymity for complainants in rape cases. In doing so, Heilbron recognised that the publicity surrounding allegations of rape may be “extremely distressing and even positively harmful”.

Heilbron also considered briefly the case for anonymity of defendants:

Notwithstanding the reservations of Heilbron, the Sexual Offences (Amendments) Act 1976 introduced anonymity for both complainants and defendants. The legislative intent in providing anonymity for defendants was to protect them from damaging consequences of false allegations. However, this measure was repealed in 1988 on the grounds that being accused of rape was no different from being accused of other serious crimes and did not warrant special treatment. Moreover, that the principle of equality between defendants and complainants was a false comparison.

Under current legislation [the Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 1992], lifetime anonymity remains in place for complainants of rape and other sexual offences and despite frequent debate in the Lords and the Commons, plus research and opportunity to do so, Parliament has not legislated again on this specific issue. Notably for example:

2003: A move by the House of Lords to extend anonymity to defendants during the passage of the 2003 Sexual Offences (Amendment) Bill was defeated.

2003: A Home Affairs Select Committee report recommended that anonymity be granted between allegation and charge, in order to protect potentially innocent suspects from damaging publicity yet safeguarding the public interest in reporting criminal proceedings.

2009: The Stern Review (a report by Baroness Stern of an independent review into how rape complaints are handled by public authorities in England and Wales) considered the need for defendant anonymity as a matter “linked” to the matter of false allegations of rape. It concluded, “We make no recommendation on anonymity for defendants but note that it is often raised and the concerns will undoubtedly continue. A full examination of the issues would be helpful to the debate”.

2010: Power-sharing agreement between the Conservatives and the Lib Dems included a pledge to “extend anonymity in rape cases to defendants”. However, despite early promises of a free vote on the issue, this agreement ended following a Ministry of Justice Report “Providing anonymity to those accused of rape: an assessment of evidence”. This Report concluded: “Overall, this review of evidence on providing anonymity for rape defendants found insufficient reliable empirical findings on which to base an informed decision on the value of providing anonymity to rape defendants.” The focus moved to a non-statutory solution.

2015: The call to grant anonymity to suspects between allegation and charge was repeated in the wake of further high-profile suspects being named in the press, including Cliff Richard. The Home Affairs Select Committee recommended that “the police should not release information on a suspect to the media in an informal, unattributed way. If the police do release the name of a suspect it has to be limited to exceptional cases, such as for reasons of public safety.” Secondly that “it is in the interests of the police to demonstrate, post-Leveson, that there is zero tolerance for informal leaks to the press. Police forces need to monitor and publish the number of instances where the identity of a suspect in their area has found its way into the public domain without an attributed source.”

2016: Sir Cliff Richard, Paul Gambaccini and other high-profile men launched a campaign to change the law so that suspects in rape cases cannot be named unless charged. End Violence Against Women called for the campaign to be dropped and argued for open and transparent justice.

2016: An amendment to the Policing and Crime Bill was tabled in the Lords which would grant anonymity to individuals being investigated for sex offences until a decision is taken to actually charge them. The Government was again not persuaded that legislation was the way forward. The reason given was that the police should have operational independence when deciding whether to name a suspect and that ultimately the Government did not wish to create an environment where victims are reluctant to come forward.

2018: Cliff Richard ruling and the calls for ‘Cliff’s Law’.

…so having reached the Cliff Edge where to now?

Conclusions – lessons from history

Even a brief review of history tells us that this is far from a straight-forward decision. It is a decision that has taxed even the brightest of legal and political brains and unsurprisingly, therefore, it is a decision upon which Parliament and politicians have changed their minds or ‘kicked into the long grass’ for decades.

That said, history also tells us that this is not a decision that can simply be left to the “careful judgment” of the police or the media, or indeed to the Courts who can only do so much to clear up problems.

It cannot be forgotten that we live in a time of unprecedented levels of sexual offence cases being tried in our Courts and when we have an Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse continuing its work.

At the very least, the time has come to glean reliable empirical evidence on the impact of defendant anonymity, in particular in rape and sexual offence cases, so that there can be proper and informed public debate and clarity of thought brought to bear on such a fundamental legal issue of our times.

So where does this case feature on the journey towards or away from defendant anonymity? Well we are certainly not at the Cliff Edge, rather this case represents a more interesting diversion on that particular journey and the law remains unchanged.

As I made clear on judgment day, it is important that in appropriate cases the police are not cowed by the Sir Cliff judgment, and do still at the very least consider reporting the name of an individual, when that action may enable other victims to come forward to strengthen the case against that individual.

David Malone is a prominent human rights and criminal barrister specialising in the field of sexual violence and victims’ rights practising from Red Lion Chambers. He was assisted by Zoe Chapman, a pupil barrister at Red Lion Chambers.

When we think of IPOs, the legal world isn’t the first to come to mind, but every year large law firms opt to engage in a public offering, inviting outsiders to be part of their expansion. Martin Ramsey, Partner at MHA MacIntyre Hudson, believes this practice should be followed with much caution, citing the risks and considerations to make, in particular regard to the long term health of the business.

It appears that IPOs in the legal sector are back in vogue. There was a flurry of activity and interest following the initial success and expansion of Slater & Gordon and the introduction of so called ‘Tesco Law’*, but this appeared to quickly wane, with the exception of Birmingham’s Gately plc which listed on AIM in 2015.

In 2017 we saw two further IPOs and in recent weeks both London’s Rosenblatt Solicitors and Knights Solicitors from the Midlands have indicated their intention to follow suit. However these are a mere ripple in comparison to DWF’s confirmation of the rumour that they are also considering a public offering.

It seems that firms that have been sitting back and watching Gateley from afar have now decided that the time has come to take the plunge themselves. The performance of Gateley since its IPO has been strong, and it has certainly used a share of the funds raised to grow by acquisition.

So, does this mean that IPOs should be on the agenda for most firms? In my opinion caution should be exercised and the long-term future given careful consideration.

Who benefits in the event of an IPO? The equity partners at the date of the transaction are likely to be the main beneficiaries as their share in the business attracts a premium. The consideration is likely to be a mixture of cash and shares in the business, and it’s likely that the partners at the top end of equity are going to profit most. This is the first concern; those senior partners who are likely to reap benefits in the short term are likely to be key decision makers and the most influential people in the business. When there is a significant reward dangling in front of them, are those partners truly thinking of the long-term health of the business?

Many firms have spent a long period of time extracting themselves from ‘goodwill’ arrangements with exiting partners and indeed from retired partner annuities. By listing, there’s a risk that the current generation of equity partners are taking their goodwill out of the business. Once this value extraction has happened it’s very difficult to unwind – taking a business private again in the future would be hugely expensive as the partners would have to buy back their own business from the investors at market value. This would lead to a highly geared business and partners.

There’s a good reason that the majority of professional practices operate through a partnership (or LLP) structure; the fit is excellent for a participative collegiate business that’s handed between generations in a highly flexible manner. There is also something to be said for partners being ‘in partnership’ together – in my world that still means something.

The other concern relates to the next generation of partners (or employees under a corporate structure). Once the current generation have taken their slice, the next generation is left with an external investor to service from the profits of the business. In order for post-deal profit per partner to remain in-tact, the profitability of the business must rise proportionately after the float. If this were possible organically then the IPO would not have been required in the first place, therefore some sort of incremental investment is going to be required to achieve the uplift. This is probably the greatest area of risk in relation to the IPO – how confident are management that the funds retained in the business after the float can be applied in a way that generates a greater return than the cost of keeping the external shareholders happy?

We have all seen the examples over the years of legal practices raiding the cash pot when there is a property windfall, and we have seen the consequences of short term thinking in this respect. When an IPO happens, are the partners going to be able to allow a significant proportion of the proceeds to be reinvested into the business, or is the majority going to be paid straight out to the partners? If the latter, then the rate of return required on the retained funds in order to break-even is likely to be unachievable.

So does this mean IPOs can never work in the legal sector? The short answer is that those with first mover advantage are much more likely to make a success of the process, but it’s difficult to see the market being able to handle a significant number of listed practices. My personal choice would certainly be to remain a partner in an LLP. The true test will be when the latest clutch of firms who have or are planning to IPO reach the end of their partner lock-in periods – it will very quickly become apparent whether partners are happy to remain in that environment.

UK Law firm IPOs:

Gateley 2015 £30m

Keystone Law 2017 £15m

Gordon Dadds 2017 £20m

Knights considering

Rosenblatt considering

DWF considering

*Allows firms to operate as Alternative Business Structures (ABSs). They can offer legal services alongside businesses such as supermarkets, banks, and High Street shops.

Where an organization is based affects the technologies being used by its legal department, according to the latest Sharplegal research from Acritas, who discovered that it is legal departments in UK organizations that should be most concerned.

Market research experts Acritas have been investigating how innovation and technologies in the legal industry are evolving, based on first-hand experiences of over 2,000 senior in-house counsel.

Upon analysis of feedback on innovation, provided during their 2017 global Sharplegal survey, Acritas noticed there was a lot of focus on new technologies. So in 2018, their Sharplegal research began investigating this area further and quickly identified notable differences across geographies, in the technologies being used and not used by legal departments.

A number of different technologies were tested from virtual deal rooms through to AI.

Legal departments in UK organizations are definitely falling behind the curve, with 25% not using any of the technologies Acritas investigated, compared to 11% in the US. In fact, UK in-house counsel are less likely to be using every technology tested in the Sharplegal survey.

E-signatures are used by 61% of US legal departments compared to 49% of Mainland European and 37% of UK legal departments. E-discovery is used by nearly four times as many legal departments in the US than their European counterparts. Lisa Hart Shepherd, CEO at Acritas said: “We expected the US to lead on the use of litigation related technologies, but the UK is using less of everything we tested.”

However, the US wasn’t leading on everything, some new technologies were used more by European legal departments. For example, searchable knowledge-bases are used by 48% of legal departments working in European organizations, compared to 25% of US and 16% of UK corporate legal departments.

Lisa added: “A lack of use doesn’t necessarily relate to an aversion. When under so much pressure to manage risk and drive up the value delivered by their corporate legal departments, change can be pushed back down the agenda. But for GCs looking to improve efficiency, understanding which technologies are working well for other legal departments around the world can be invaluable.”

(Source: Acritas)

As a law student you’re likely to spend a fair bit of time writing answers to problem questions, so it’s best to be prepared. Below Lawyer Monthly’s latest law school & careers feature benefits from expert top tips from Emma Jones, lecturer in law and member of the Open Justice team at the Open University.

Problem questions can help you to develop valuable skills around identifying relevant information, applying legal principles to specific scenarios and writing advice in a clear and logical manner. Here are some top tips on how to approach this type of question.

OK, so this really applies to all types of assignments, but with problem questions there can be a pretty lengthy scenario for you to get to grips with. It can help to highlight or underline, but even better try making a flow chart or chronology of events, or a spider diagram detailing the involvement of each party.

One common way to approach analysing problem questions is the IRAC method – identify the Issue, explain the Legal Rule, set out its Application and reach a Conclusion based on this. Depending on the scenario you’re given, you might need to work through this process several times, for example, once for each party involved or each potential cause of action

When it comes to explaining the legal rules that apply to a scenario, it can be tempting to quote sections of statute or parts of judgments. Although it’s great to reference legislation and cases, setting out their meaning in your own words really demonstrates your understanding. It can be tricky to get the balance between keeping the original meaning and putting it in your own way, but it does get easier with practice.

The Application part of a problem question is key. It can be very tempting to jump from the legal rule to a conclusion, but you need to take your reader through your thought-process step-by-step. Often, there is no one “right” answer to a scenario, the key is to construct a clear and sound argument using legal authorities and explaining how they apply to the facts.

This leads neatly onto the next point – structuring your work carefully. Your Law School may have its own rules on this, for example, whether or not to include a brief introduction and when to use headings. It is important to follow these. The general rule is to try and make your structure and writing as easy to follow as possible. Imagine you are writing for an intelligent lay person with no previous knowledge of law. In fact, you can always ask a friend or family member to take a look to see if they can follow what you’re saying.

When you are trying to write a conclusion, you may find that there are parts of the scenario that are a little ambiguous or where there is potential for different outcomes. If that is the case, it is fine to indicate that you can’t reach a final conclusion, but it is important to explain why not. On the other hand, if you can give a conclusion, you should try and do so. It’s usually fairly clear when someone has lacked the confidence to make a decision.

Problem questions can be challenging, but they are a great way of developing key skills which are needed in plenty of careers, not least for working on the legal profession. Just remember, one day you may have a real client in front of you, and be very glad you had the chance to practice first!

Lawmakers are facing a head to head conflict with the US President as the effects of the steel tariffs are felt across the US. Below Geoffrey R. Morgan, Founding Partner at Morgan Legal Group, LLC, comments on the overall impact of the steel tariffs on the nation, and the consequences that may come.

Following my commentary on the American Institute of International Steel’s lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of President Trump’s steel tariffs, it has become apparent that the president’s actions have angered more than just steel consumers and handlers in the United States. They have also angered lawmakers, particularly those whose constituents in farming and manufacturing towns fear retaliatory tariffs.

According to multiple reports, Senator Orrin Hatch (R – Utah) has warned President Trump that, should existing tariffs and trade threats not subside, he would support legislation to limit the President’s trade authority as currently delegated by Congress. Sen. Hatch, who has been known as an ally to the president, called Trump’s recent trade policies “misguided and reckless” and is reportedly working with colleagues, both within and outside the Senate Finance Committee, to determine the likelihood of getting the votes needed to limit the president’s invocation of Section 232. No vote has yet been scheduled.

Now that the effect of the tariffs is being felt in congressional districts across the country, they have been widely criticized by almost all steel-using sectors and industries. Many report steel prices have risen by 30% or more, including that which is manufactured domestically.

Recall that the American Institute of International Steel’s lawsuit challenges the constitutionality of the tariffs as an unauthorized delegation of legislative authority to the President under the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. Although I originally opined it would be difficult to overturn the legislation with a Republican congress – particularly given the lack of precedent – it now appears the rift between the executive and legislative branches has never been greater and, with growing steel prices and constituent dissatisfaction, lawmakers are considering doing just that.

Most people in the United Kingdom are at risk of not having their final wishes respected after their death as they have no will in place, according to new research from Which? Legal.

The survey revealed that less than a third (31%) of those in Scotland have written a will, compared with 35% in Wales. In England, results were almost as poor with just four in 10 (42%) having a will in place.

A staggering six in 10 (61%) told us that they don’t have a will. When we asked why, four in 10 (38%) told us that they had nothing worth inheriting, one in five (20%) said that writing a will had not occurred to them, and 16% said they had been too busy.

Which? Legal found that those that did have a will in place waited until they were 47 years old, on average, before writing it

When asked whether they would leave money to charity, two thirds (67%) said that they would not. Of those, the majority (64%) said this was because they wanted to leave their money to family.

There was a clear generational divide in attitudes towards charitable giving, with 57% of 18-24 year olds saying they would leave money to charity in their will, while just 19% of those aged over 65 said they would make some form of donation.

Risks of not having a will:

Darren Stott, Managing Director of Which? Legal, said: “It’s clear that people don’t appreciate the risks of not having a valid will in place. Even if you think you have nothing worth inheriting, this is often not the case.

“Whatever stage of life you’re at, a will offers peace of mind and ensures that your money, property and other possessions go to the right place.

“Giving money to charity in your will can be a tax efficient way to pass your money on.”

Percentage of people with a will (regional breakdown):

(Source: Which? Legal)